We should all spend some time, however fleetingly, doing what George Sharpe did.

George was a birder.

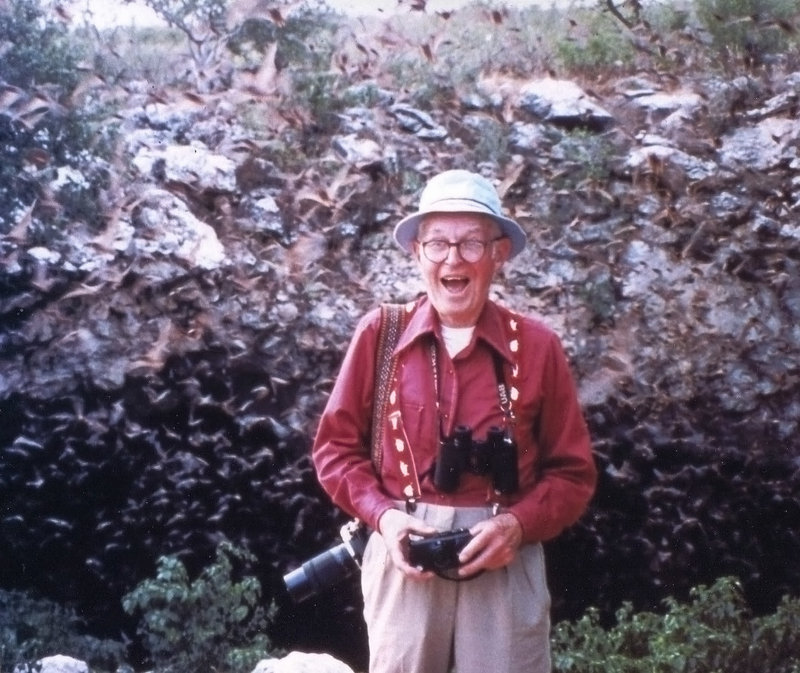

He died just over a week ago, a mere three months short of his 100th birthday. And if you want to gauge the impact he had during his near century on earth, look no further than the migratory bird sanctuary that surrounds the small ponds at Portland’s Evergreen Cemetery.

“George had been coming down here for more than 70 years,” said Arthur Stackhouse of Pownal, one of the regulars at the cemetery who took a few moments Friday morning to reflect on their friend and, when it came to all things feathered, their mentor.

“I was here just this time last year, and here he was down here all by himself, just checking around to see what was going on,” said Jerry Davis of Portland. “He really was one of a kind.”

Some people spend their spare time collecting coins. Others fish, play golf, tend gardens or, alas, let the years slip by doing nothing at all.

George Sharpe looked for birds.

As a young boy growing up near St. John, New Brunswick, he’d head out in his canoe and paddle up and down the river near his home listening and watching and forever memorizing the call of a warbler, the coloring of a sparrow, the nesting habits of a wren and myriad other minute characteristics of the 900 or so different species of birds that populate North America.

“He was very frustrated (as a boy) because he’d go to the library to look up the female ducks, and there were no pictures of female ducks,” said his daughter Jocelyn Key. “I mean, there were no bird books at all.”

Ah, but there were birds everywhere. Moving with his family to Portland in 1925 at the age of 15, George brought his passion for birds with him.

From his graduation from Portland High School in 1925 to his marriage to Ruth Fox in 1940 to his service with a field artillery battalion in Europe during World War II to his 34-year career with the auditing department of Maine Central Railroad, he was a man unusually attuned to his environment.

He didn’t own a car. Instead, he’d walk each day between his home on Capisic Street and his office on St. John Street — acutely aware of the sparrows, the nuthatches, the mourning doves and the chickadees that most people go through their days looking at without truly seeing.

“I worked for the telephone company, and I’d see George walking along, so I’d stop my telephone truck and say, ‘George, hop in!’” recalled Stackhouse, 79, who took Sunday school lessons from George 70 years ago at what was then the West Congregational Church.

“But he’d never take the ride,” Stackhouse said. “He’d always say, ‘That’s OK, Arthur. I need the exercise.’ And off he’d go.”

As children, Jocelyn and her two older sisters didn’t quite know what to make of their father, who’d traipse off to Capisic Pond or Evergreen Cemetery at every opportunity to add to his “life list” of species he’d spotted over the decades.

“We always thought he was a strange man. We were kind of embarrassed as kids,” Jocelyn recalled with a chuckle. “In the winter, he’d shovel the walkway to the bird feeders before he’d shovel us out.”

That perception changed for Jocelyn back around 1975. She was in her mid-30s by then and living with her husband in Florida when, in anticipation of a visit from her father, she decided it would be nice to prepare a list of local species to give George upon his arrival.

“So I went on a little birding trip,” Jocelyn said. “And I got hooked.”

Indeed. In his later years, George eagerly joined his daughter on birding trips to Trinidad, Canada, California, Alaska and twice to Texas, where he once delighted in a swarm of just-awakened bats while the rest of the party cowered behind rocks.

The more she observed him observing birds, the more Jocelyn marveled at her father’s skill.

“He was amazing,” she said. “He could hear just a little chirp from a bird and identify it that way. Even at 99, he could still hear a lot.”

Avid birders can be a strange breed. Some, noses in the air, cackle on and on about their ever-growing list of sightings. Others add to their lists secretively, not wanting to share a discovery with the competition.

Not George. He’d no sooner arrive at Evergreen Cemetery — a mecca for local birders this time of year — when six, eight, maybe even 10 other visitors would fall in behind him, stepping where he stepped, looking where he looked, hanging on his every word and peppering him with questions.

“He was just a terribly good teacher,” said Stackhouse, who in recent years took George all over Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts in search of rare species. “And even at 99, he had the most wonderful penmanship. I’d love to have records like his.”

“Everyone would follow George,” agreed Davis. “Let’s say you saw a new bird yourself — say, a blue warbler. And you’d ask, ‘When did you first see that one, George?’ And he’d say, ‘It was 1934.’ And he could give you the date, where he saw it, everything. His memory was amazing.”

“When I think of George, two words come to mind,” said Bob Cash of Cumberland. “Class act. That’s what George was — a class act.”

Stackhouse, who didn’t take up birding in earnest until after he retired, has 450 or so species on his life list. Cash’s list currently stands at 528, while Davis just hit 560.

George’s list, if you include the species he spotted from the trenches during World War II, stood at 665.

“But he never saw a whippoorwill,” Stackhouse said wistfully. “That’s one he always wanted to see, a whippoorwill.”

Saturday morning, a noticeably large flock of Maine birders gathered at Woodfords Congregational Church to bid George farewell.

Over the next few weeks, they’ll descend on Evergreen Cemetery early each morning to witness the annual migratory “pulse” of species heading north for the summer.

Only this time, for the first time in anyone’s memory, the short, wiry man with the keen ears, sharp eyes and ever-present smile won’t be there to revel in a world that passes daily right over most people’s heads.

“He was a birder all his life,” said Stackhouse. “We’ll all miss him.”

As will his birds.

Columnist Bill Nemitz can be contacted at 791-6323 or at:

bnemitz@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.