PORTLAND – State Rep. Herb Adams’ reverence for history is well documented.

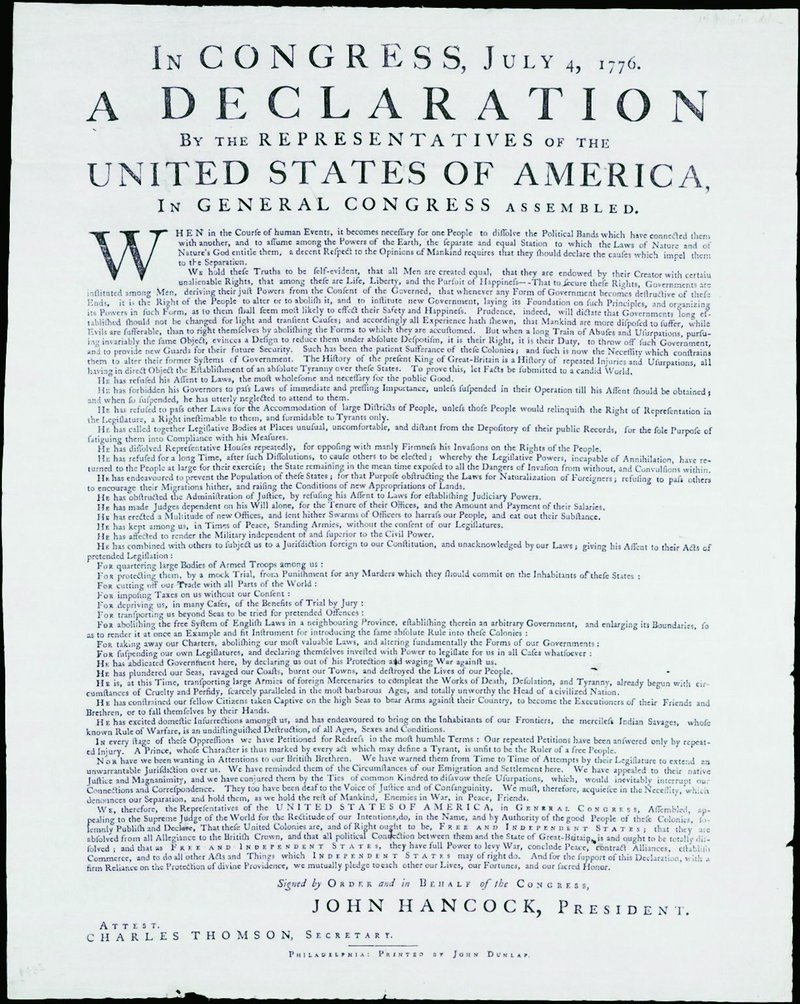

Each Independence Day, he proudly and publicly reads the Declaration of Independence from a replica of a broadside, a large printed sheet, copies of which were sent to towns in 1776 to inform the colonists that ties to the crown had been severed.

The original broadsides, printed to announce the Continental Congress’ bold act, are priceless to the communities whose history they represent. And they can fetch high prices from collectors.

A new law aims to stem such trade in endangered historical documents.

Changes in state law that recently took effect recognize any document of historic value as state, county or municipal property unless specifically relinquished by the government.

“The declaration is America’s birth certificate” said Adams, who championed the new legal protections in the Legislature.

Last year, the state lost a high-stakes battle before the Virginia Supreme Court over the ownership of a Declaration of Independence broadside, which had been sold at auction with the estate of a descendant of the town clerk of Wiscasset, originally called Pownalborough.

The court ruled that the document — printed by Ezekiel Russell in Salem, Mass. — was not a government document because it was created before the state’s public records law was written and had not been kept as an official town document. That meant the collector who had paid $475,000 for it could keep it.

A broadside from North Yarmouth was sold, but the state archivist was able to use an antiquities law to get it returned in 1999.

In 2000, a Declaration of Independence broadside from a Philadelphia printer, like the one kept at the Maine Historical Society in Augusta, sold for $8 million, Adams said.

He figured the state’s heritage needed legal protection.

With the backing of veterans organizations and historians, the Legislature approved the changes. When any such document turns up in the future, it can be preserved.

The law also protects more recent documents that will become the historical record for future generations, he said.

“Maine, being the nation’s attic, kept a good number” of broadsides, Adams said, although the exact number in existence isn’t known.

“There are rumors of many more of these out there, stuffed in town records in the back room and forgotten, in the bundle of papers that were in the former town clerk’s back shed before there was a town hall,” Adams said.

The Continental Congress and Gen. George Washington had copies of the declaration printed “to tell people about the separation and the terrible war they knew would be coming,” Adams said. Broadsides were read from church pulpits and at town meetings.

“You have to remember, it was treason to write it, treason to sign it, treason to read it aloud,” Adams said. “If the principles are worth the paper they’re printed on, then it’s worth protecting the paper they’re printed on.”

Staff Writer David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at: dhench@pressherald.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.