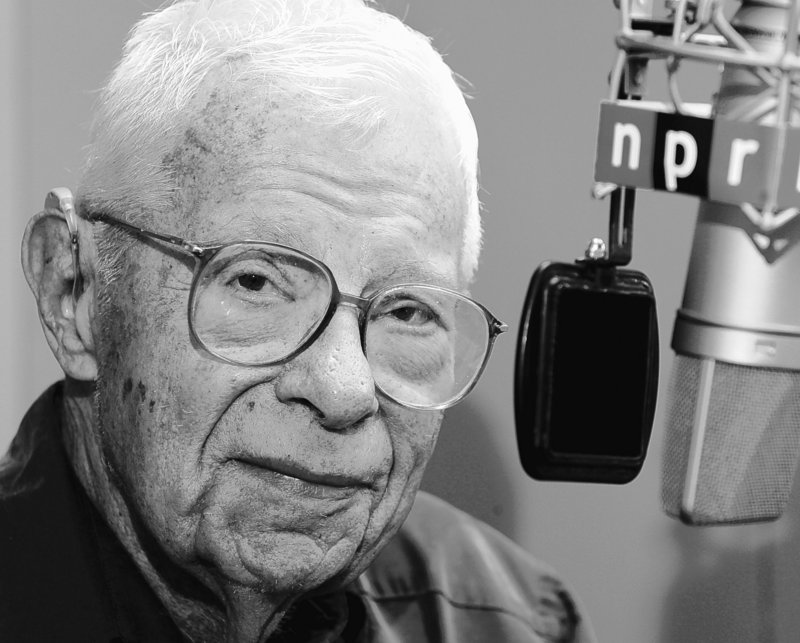

LOS ANGELES – Daniel Schorr, who became the elder statesman of public radio after decades as a feisty television broadcaster for CBS and CNN, has died. He was 93.

Schorr died Friday morning after a short illness at a Washington hospital, National Public Radio announced. His last broadcast on that network aired July 10.

A working journalist for more than 60 years, the indefatigable Schorr was the last active member of Murrow’s Boys, the legendary group of journalists who worked at CBS News in the 1940s and ’50s under Edward R. Murrow. He was a high-profile CBS reporter for 23 years before leaving amid controversy in 1976.

In 1985, after several years at CNN, he joined National Public Radio, where as a senior news analyst he was heard regularly on the “Weekend Edition” and “Week in Review” programs.

“Nobody else in broadcast journalism — or perhaps any field — had as much experience and wisdom” as Schorr, “Weekend Edition” host Scott Simon said Friday. “I’m just glad that, after being known for so many years as a tough and uncompromising journalist, NPR listeners also got to know the Dan Schorr that was playful, funny and kind. In a business that’s known for burning out people, Dan Schorr shined for nearly a century.”

Having a long view of national and world events gave the reporter who once covered Watergate and found himself on President Richard Nixon’s infamous “enemies list” a perfect second career as a sober commentator.

Schorr said he “breathed the breath of freedom” at NPR. “Nobody ever told me what not to do.”

During his CBS career, he addressed serious subjects in the United States and on foreign assignments and won a Peabody Award for his hourlong CBS documentary on “The Poisoned Air.”

But controversy followed him, both because of his aggressive coverage of stories and his sometimes cantankerous relationships with his superiors and co-workers. New York magazine in 1975 dubbed him “the great abrasive.”

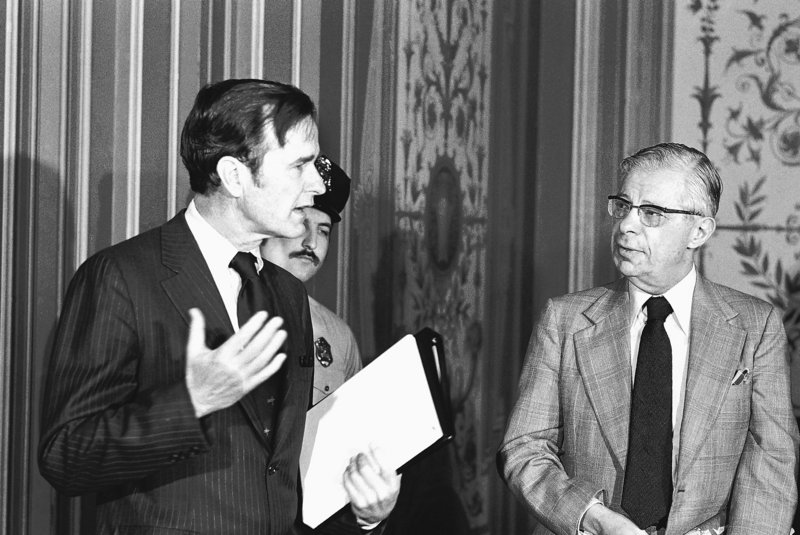

That year, as a CBS reporter, Schorr covered the House Intelligence Committee hearings on CIA covert operations, including assassination plots. Schorr was slipped a copy of the intelligence committee’s draft report, the contents of which he reported on the CBS Sunday News. He was the only journalist to actually have a copy of the report, although The New York Times had seen it and had written about it that same day.

A few days later, partly in reaction to Schorr’s reporting, the House of Representatives voted to lock up the remaining copies of the draft report and keep the final report secret. Schorr decided that, since he had the only copy of the report in general circulation, he had a responsibility to get it published in full.

When he turned to CBS for help, however, he did not get an immediate answer, so he offered the report to the Village Voice, a left-leaning weekly newspaper in New York. The Voice published a 24-page supplement with the headline: “The Report on the CIA That President Ford Doesn’t Want You To Read.”

The low point during this time came when Schorr “dissembled” — his word — by not disabusing a CBS executive of the notion that perhaps Lesley Stahl, who worked with Schorr and who was then engaged to and later married Village Voice writer Aaron Latham, was involved in getting the report to the Voice.

Schorr said later that he was stalling for time in order to figure out how best to protect the person who had given him the report. But Stahl, who felt he had fingered her or Latham as a thief, was furious. Their colleagues took her side.

Although Schorr called Stahl to say he was sorry, his behavior engendered so much ill will that he was no longer welcome in the Washington bureau where both had been working.

The second and more serious consequence of getting the report published came when the House committee demanded to know Schorr’s source. He refused to divulge it, risking a contempt citation.

CBS executives, upset at Schorr’s giving the Voice material that they considered CBS property, asked him to resign. They agreed to a secret suspension until the committee hearings were complete and provided him with legal representation.

Later, when Schorr was questioned by the committee, he made a strong defense of the First Amendment: “To betray a confidential source would mean to dry up many future sources for many reporters. The reporter and the news organization would be the immediate losers, but the ultimate losers would be the American people and their free institutions.”

A week after he appeared, the House Ethics Committee abandoned its effort to have Schorr cited for contempt. CBS News President Richard S. Salant, impressed both with Schorr’s eloquence and the positive public response to his testimony, tried to get Schorr to stay at the network. He refused.

“Difficult as Dan was from time to time, he was a great investigative reporter,” Salant wrote in his 1999 memoir.

After writing “Clearing the Air” (1977), which mostly gave his side of the events of the previous two years, Schorr taught briefly at the University of California, Berkeley, and wrote a syndicated column.

In 1979, Ted Turner recruited him for his new venture in 24-hour journalism, Cable News Network.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.