JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — More than 1 million people are expected to participate in what amounts to the largest-ever public opinion poll on the nation’s new health-care law.

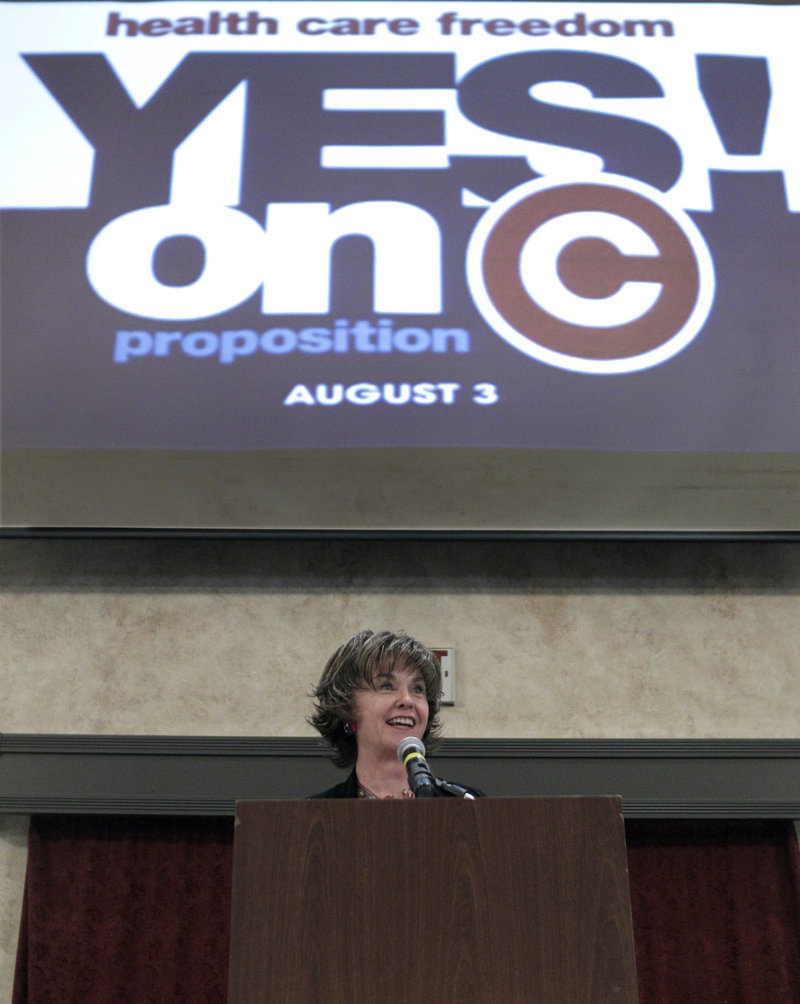

On Tuesday, Missouri will become the first state to test the popularity of President Obama’s top policy accomplishment in a statewide ballot proposal attempting to reject its core mandate that most Americans be covered by health insurance.

The legal effect of Missouri’s measure is questionable, because federal laws generally supersede those in states. But its expected passage could send an ominous political message to Democrats seeking to hang on to their congressional majority in this year’s midterm elections.

The Missouri measure, shepherded to the ballot by Republican state lawmakers, is a glaring example of the twisting, troubled politics surrounding the health care overhaul. After years of campaigning for reform, Democrats finally accomplished it. Yet it is Republicans who now are highlighting the law in their campaigns, while Democrats are largely silent.

From Florida to Washington and numerous states in between, Republican candidates for the U.S. Senate and House — and even for local offices that have little to do with the federal law — are calling for the repeal of what they derisively dub “Obamacare.”

It’s reached a point that “the debate over the health care bill is not really so much over the specifics of the health care bill,” said Florida-based Democratic consultant Marc Farinella. “It’s become a surrogate for a debate over the direction of the country, or the direction of the Obama administration.”

A year after raucous town-hall forums, and months after Obama signed it into law, the overhaul remains divisive and national polls differ on its popularity. A Kaiser Family Foundation poll found approval grew to 50 percent while disapproval shrunk to 35 percent in July. A Pew Research Center poll showed the opposite, with approval falling to 35 percent and disapproval rising to 47 percent.

In the swing state of Missouri, where Obama narrowly lost to Republican Sen. John McCain in the 2008 presidential elections, the law appears particularly unpopular.

Sixty-one percent of respondents to a Mason-Dixon poll conducted this month for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and TV station KMOV said they opposed the law. Opinion generally split along party lines, but among the key category of independents, 65 percent said they disapproved.

If passed by voters, the proposed Missouri law would prohibit governments from requiring people to have health insurance or from penalizing them for paying health bills entirely with their own money. That would clash with a key provision of the new federal law requiring most Americans to have health insurance or face fines starting in 2014.

Similar measures are to appear as state constitutional amendments on the November ballot in Arizona, Florida and Oklahoma. And similar laws already have been enacted — without statewide votes — in Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana and Virginia.

Supporters hope the state measures will provide ammunition for court challenges over the constitutionality of the federal insurance mandate. But the federal law already has become a key part of Missouri’s primary elections.

The defiant ballot measure is backed both by U.S. Rep. Roy Blunt, the Republican front-runner for U.S. Senate, and by his Republican rival, state Sen. Chuck Purgason, a favorite of many tea party activists. Blunt’s TV ads claim the leading Democratic Senate candidate, Secretary of State Robin Carnahan, would “rubber stamp” Obama’s agenda of “more government control of health care.”

Carnahan, while expressing support for the health care law, generally has ignored it in her stump speeches, instead focusing her rhetoric against bailouts of banks and big corporations.

Various Republican candidates in Missouri have contributed money to a specially created campaign committee for the ballot measure, which has been running radio ads and printing yard signs.

Opponents, who failed to knock the measure off the Missouri ballot with a lawsuit, had no organized campaign until several college-age students recently launched a Facebook-driven effort to hold opposition rallies in Kansas City and St. Louis.

“We want health care for all Missourians, and we think this (federal law) is the best way we can get health care,” said Caleb Files, an 18-year-old fast-food manager in Kansas City who is coordinating publicity for opponents.

The Missouri Hospital Association now is mailing letters to hundreds of thousands of homes suggesting that hospitals could incur costs of about $50 million annually in treating the uninsured if the state proposal is passed and upheld in court.

Even in states lacking similar ballot measures, the federal law has emerged as a key campaign theme.

In Arkansas, opposition to the “job-killer” health-care law is a central part of Republican U.S. Rep. John Boozman’s challenge to Democratic Sen. Blanche Lincoln. Wisconsin Republican Ron Johnson, running against three-term Democratic Sen. Russ Feingold, has called the health overhaul “the greatest assault on our freedom in my lifetime.”

The law also has played a role in Michigan’s governor’s race, where all five Republican candidates have signed pledges not to force residents to get insurance as the federal law requires.

But the effect of the health care law on the general election is less clear. And opinions could change as parts of the law soon take effect, including the issuance of checks to seniors to fill the so-called prescription drug doughnut hole and the ability for children up to age 26 to stay on their parents’ insurance plans.

“It’s going to be a problem for the Democrats who are in those maybe 50 or 60 Democratic-held (congressional) districts that are in play — districts that have tended to vote for Republicans in the past,” said Alan Abramowitz, a political science professor at Emory University who has observed similar health-care campaign themes in his home state of Georgia.

But otherwise, “I think it’s going to be based more on people’s overall feelings on Obama and the economy and less about health care,” Abramowitz said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.