PORT CLYDE – Barbara Ernst Prey has shown her watercolor paintings of Maine around the globe. She has spent her life in elite circles, hobnobbing with art critics, millionaires and powerful politicians from New York and Paris to Washington, D.C., and Madrid.

Curators, collectors and educators wear a path to her gallery door down here on a neck of land made famous by the likes of Andrew Wyeth.

But Prey, in a moment of candor made all the more refreshing by an unbridled laugh, says none of her success might have happened at all if not for the endless hours she spent on the road carting her kids around the Northeast for hockey games. Her son and daughter, now both in college, are devout hockey players.

Prey, above all else, is a hockey mom.

For years, every winter weekend morning Prey woke up before light, packed up heavy bags of hockey gear and drove from practice to games to tournaments across New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Prey has a summer place in Tenants Harbor, just up the road from her gallery in Port Clyde, but the family lives most of the year on Long Island, N.Y.

This winter will be no different, except the weekend commute will be a little longer. Her daughter, Emily, plans to play for the women’s team at Williams College in western Massachusetts, Prey’s alma mater. Prey will be there for her games at home in Williamstown, Mass., and as many road games as she can make. Meanwhile, her son, Austin, plays on the club team at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire.

“Someone asked me the other day what it’s like to be famous. But I don’t look at it that way at all,” Prey said during an interview at her gallery, Blue Water Fine Arts.

“Having two children play hockey really keeps you grounded. There’s no time for your own success to get to your head, because you’re always thinking about the next practice or the next game. There’s always another priority in your life, and it’s never your own. It’s about getting to the rink on time, being there for your kids and hanging out with other parents.”

SHARPENED VISION

Being a hockey mom informs Prey’s artistic pursuits in other tangible ways. She believes that spending so much time on the road has helped her see the landscape differently than she might if she stayed close to home. She’s covered a lot of turf and seen a lot of beautiful things — drafty hockey rinks notwithstanding. It has also given her time on her own to think, sketch and keep up with her reading and correspondence. It has forced her to slow down, take stock and sort her priorities.

“All those years of looking has really helped build my visual vocabulary,” she said. “You’d never guess, but I think in many ways, being a hockey parent really has benefited my work. It’s added a different perspective. Because of hockey, I’ve seen a lot of things.”

Prey is in the midst of her annual summer exhibition at Blue Water Fine Arts. This year’s show, “Soliloquy,” finds her in a contemplative state, as she offers a visual perspective on the changing texture of the Maine coast and its declining fishing industry.

ENVIRONMENTAL QUEST

In her new work, Prey adds an element of social commentary to her paintings. She showcases her environment with a sense of urgency, striking the tone of an environmentalist and advocate. In one series, she paints a young fisherman tending nets on the pier. It’s colorful and evocative. The apprentice pulls twine through the net to finish a mending job. In one image, his dog lies lazily on the net in the foreground while his father works behind him.

The subject in the scene is a local fisherman. Prey saw him attending to his task on the pier just down from her gallery. Unknown to the viewer, but on the top of Prey’s mind, is the fact that this fisherman no longer works in local waters. He has since taken his boat to New Bedford, Mass., where the prospect of filling these nets and making a living are more favorable.

In another painting, Prey shows the interior of a fisherman’s shack. Lobster buoys, with the fisherman’s license number clearly visible, hang from the rafters, alongside neat coils of ropes. There’s a wire trap in the foreground, awaiting repair. A coffee mug, jars of paint, and containers of hardware are scattered on a workbench. We never see the fisherman, who lurks outside this view near the shop’s wood-burning stove. But this painting is very much a portrait of a man. It is a raw meditation on his life and work, and somewhat of a lament for earlier, simpler times.

In a similar view, Prey paints stacks of coils of colorful ropes. Just a few years ago, the lobsterman used those ropes for his traps. But new fishing regulations rendered them obsolete, forcing him to buy new gear.

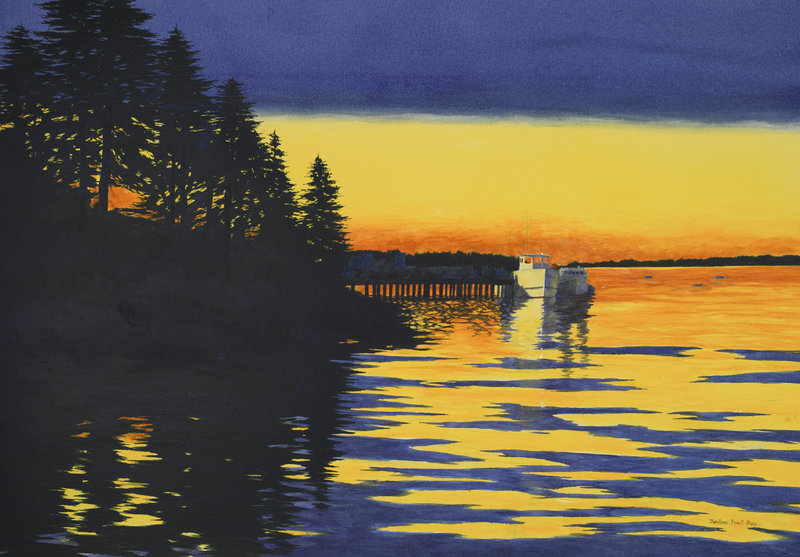

In another series, for which “Soliloquy” draws it name, Prey experiments with color. She paints ocean views of boats on their moorings during the fading light of day. The sky is richly yellow, blue and orange, and the water reflects those colors. The land is a bank of dark black, and the conclusion is inescapable: We are witnessing the sundown of a lifestyle that has been part of the Maine tradition for hundreds of years.

PURSUIT OF PATIENCE

Prey’s collectors come from around the world, and many of them make their way to her gallery in Maine to see the work in person. Among them is former NFL quarterback Boomer Esiason, who owns five Prey originals.

Esiason’s connection to Prey comes through an unlikely source — hockey. He lives near her in New York, and coached her daughter’s youth team.

At the rink, Prey distinguished herself with her calm demeanor, Esiason said in an e-mail exchange. A lot of parents were intense and vocal. Some would pound on the glass, and berate the coaches and referees. Prey was serene, he said. Her presence was welcome, and calming.

“Barbara is understanding. Hockey players are aggressive, but when you are a world-class artist it’s different — her best attribute is patience,” he wrote.

Patience is an attribute that she has learned over time, by taking the time to look beyond the obvious. She talks about “the wonder of the simple,” meaning that in every scene that we often take for granted, there is something profound.

It is that profound revelation that she hopes to capture in her work.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at: bkeyes@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.