Imagine walking the Appalachian Trail, but doing it barefoot.

Bandits lie in wait for you around the bend. You have one set of clothes and nothing to sleep on, and you sometimes have to rely on the kindness of strangers for food and water. And if you injure yourself? No antibiotics.

Such was the life of a medieval pilgrim traveling to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain, where the remains of the apostle St. James are said to be buried. The journey to the shrine at Santiago was once as important to Christians as pilgrimages to Jerusalem or Rome.

Thousands of modern-day pilgrims still walk one of the many routes to the shrine, hoping for adventure or some kind of spiritual renewal. The attraction is especially strong this year because it is a “holy year,” when the saint’s feast day (July 25) fell on a Sunday.

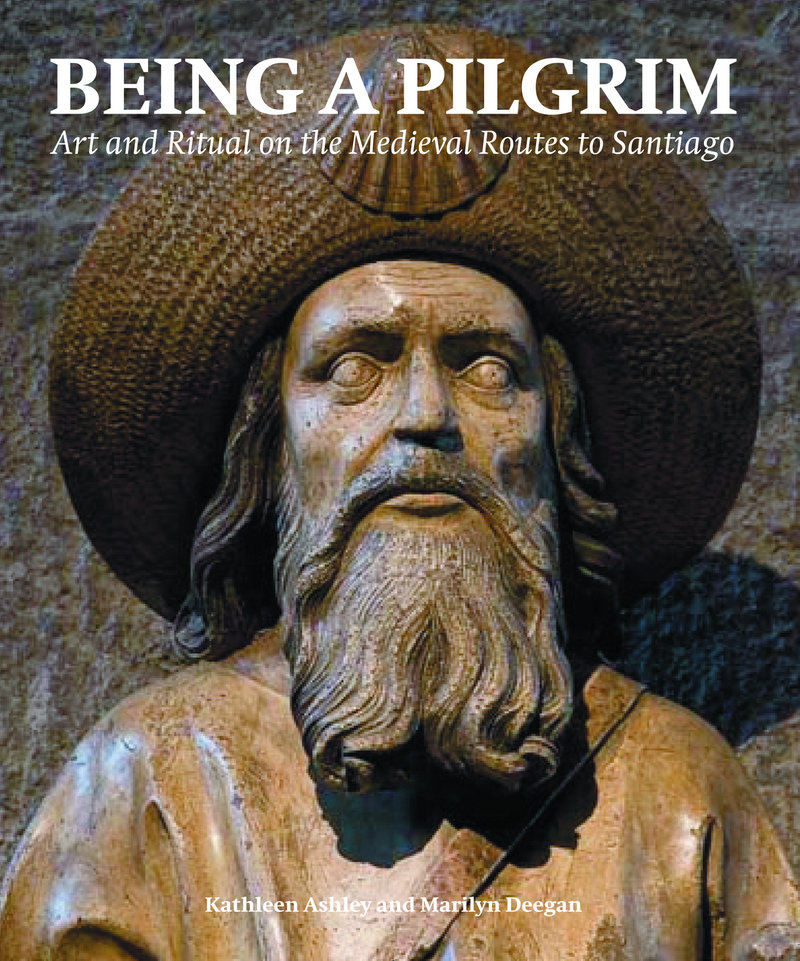

If you don’t have the time or inclination to make the trek yourself, let Kathleen Ashley and Marilyn Deegan show you the highlights in their new book, “Being a Pilgrim: Art and Ritual on the Medieval Routes to Santiago” (Lund Humphries, $60).

Ashley and Deegan spent two summers, and vacations in between, traveling the pilgrimage routes and photographing the art and architecture along the way. It’s the next-best thing to being there.

Ashley, a professor of English at the University of Southern Maine, is a medieval scholar who grew up in Angola, where her parents were missionaries. The family left when civil war broke out, and a college-age Ashley had to adjust to life in America. She attended Duke University in North Carolina, where she earned her bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees.

“It was very strange,” she said of her new life in America. “Of course, my parents were American. I spoke English very well, but I did not know the United States at all. I mean, I really, really did not know it. It took me about 10 years to adjust to the fact that I was probably not going to live in Africa. At that point, Africa was pretty much in turmoil and war, falling apart, so it was not a place you would go unless you had ended up in some practical field, like being a nurse or doctor or engineer.”

“But I became a medievalist,” she added laughing. “I don’t think they need medievalists in Africa.”

Ashley lives in Gorham with her husband, who is a retired USM English professor. Her son Christopher Ashley directed the Tony Award-winning musical “Memphis.”

Q: Have you done any of these pilgrimages yourself, before working on the book?

A: I’m a total fraud (laughing). I have written tons of books and tons of articles on medieval cultural history and literary history, and I’ve written books on saints’ cults, and of course many of the places along the pilgrimage routes are saints’ shrines. But I had never really worked seriously on the pilgrimage to Compostela in Spain. This was a totally serendipitous project for me. It was not something in my wildest dreams I ever thought I would write, but it was fun.

Q: I don’t know how many of the modern-day pilgrims you talked to, but from listening to them, is the journey still as hard as it’s described in the medieval texts?

A: It is. Basically, you’re still walking. Your feet break down. There’s still a lot of weather. At the end, people who walk 100 kilometers to Santiago can get a compostela, which is the official stamp (showing that) you’ve done the pilgrimage. But most of the people I’ve talked to have walked from Belgium, Switzerland or somewhere in France, so they’ve walked a long, long way. It is very arduous. It is physically taxing. It’s a psychic kind of experience that’s very profound.

There aren’t maybe the bandits there were during the Middle Ages. You know, there were people preying on pilgrims. I don’t think that there’s that level of violence on the route that there was in the Middle Ages, but it’s still a big adventure. So anybody who’s ever done it, it’s a major accomplishment.

The thing that’s amazing to me is that people have done it over and over again. I know people who have done it every few years. It becomes a kind of a psychic, spiritual journey that they like to take.

Q: If you wanted to, you could even stay in some of the hostels that have been there since the Middle Ages.

A: You can. Of course, many of the poorer, small ones are gone. And of course, many of the big fancy ones have been turned into fancy hotels. There is now a network of more modern hospices that you can stay in.

If you do go, whether in a car or on foot, there are many, many things that medieval pilgrims and early modern pilgrims talk about that are still there, that you can still see, especially once you get into Spain but also in southern France. The landscape hasn’t changed that much. The buildings are still there.

That medieval experience is, in some ways, still recapturable. Amazingly so, actually.

Q: This pilgrimage has become popular again in recent years. Why is that, and who is going?

A: Let me just give you some figures. In 1985, there were 2,500 pilgrims who got the compostela, which is the official certificate you’ve done it. In 1990, that had doubled to 5,000. In 1995, it was about 20,000. In 2000, it was 55,000, and in 2004, which was the last holy year, there were 180,000 people who got the compostela.

Now there are millions of people who go to Santiago, but those are the people who actually walked the requisite amount. And this year, which is the next holy year after 2004, they’re expecting over 200,000 people to get the compostela. It’s just ballooned, and it’s a little mysterious.

The one thing that happened was in 1993 UNESCO, the U.N. cultural wing, added the Camino in Spain — that is the part of the route that goes through northern Spain — to their world heritage list, so that gave it a kind of prominence. In 1998, they added all the French routes. So in the 1990s, suddenly you have a kind of a visibility, and I think that’s when it really takes off.

But also there seems to be a kind of spiritual need in modern culture. People seem to be looking not just for religion but for some kind of spiritual fulfillment.

Q: It occurs to me that the world is changing so quickly, maybe people need something like this to cope with it.

A: Yeah, because you are stripping back down to real basics when you’re on the Camino. It really is a very old-fashioned kind of experience. It’s very physical, also very mentally taxing, but also rewarding.

I think people find a kind of community when they meet at the hospice with other pilgrims, and there’s a sense that you are losing all of the language, nationality, money, status, and you’re just reduced to kind of a basic human being, and you meet with other human beings doing the same thing.

Q: How dangerous was it in medieval times? I remember reading in the book that medieval pilgrims would draw up a will and settle their debts before they left, so they must have been at least anticipating the possibility that they wouldn’t return home.

A: I think during the Middle Ages, a fair number of people actually died. If you think about it, there was very little medical care. Monasteries along the route offered medical care and a place to stay, and if you were sick, you would probably end up there.

But medieval medical treatments were so primitive by modern standards that the likelihood of dying was high, especially if you walked through France or Spain.

Now if you were from Scandinavia or England, the likelihood would be you’d take a ship to the coast and then walk in — which was a relatively short walk — to Santiago, and so that was less stressful. But people were walking across France and through Spain. The chances of some kind of harm coming to you were extremely great.

But in the Middle Ages, people did take off for these multi-month, multi-year journeys. And of course, there was no e-mail, there was no cell phone, there was no way to communicate back home.

People would be gone for months or years, and parents or relatives were left wondering if the person was still alive, and then they would or wouldn’t show up.

Q: And as you mentioned in the book, not everyone went for religious reasons. They sent criminals on pilgrimages to get rid of them.

A: The Belgians had a whole legal system based on “ship these guys out of town.”

Q: So you don’t know if the person you’re meeting on the path was a wannabe saint or a murderer.

A: It’s true. I don’t think there were huge numbers of those people, but still. And there were lots of bandits and robber types who would lie in wait along the pilgrim routes, because pilgrims were really vulnerable.

Q: What did the medieval pilgrims take with them?

A: Very little. Even now, people do carry rather large packs, but if you’re walking for several months, usually you take something to lie on. But in the Middle Ages, they wouldn’t. They’d usually have a gourd for drinking and they would have a staff to help with the paths, and they’d have a little money bag and maybe another sack with some things in them. More upscale, upper-class pilgrims tended to ride horses or mules. It was the poor pilgrims who walked, typically, or if you were really doing penitence.

There was an extra ritual at the end where you would walk from Santiago a couple of days to finish there, at “the end of the Earth,” which is on the Atlantic Ocean. There was a ritual there where you would burn all your clothes, which I imagine in the Middle Ages really needed to be burned, because you’ve been in those clothes for months.

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at: mgoad@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.