“Photography Maine: Ten Years Later at CMCA” is a large handsome show and a pleasure to see. It offers work by 150 Maine photographers and by implication picks up where an earlier CMA show left off. The predecessor, “Photography Maine: 1840-2000” was a comprehensive event that, in two parts, carried the viewer across the decades to what was then the present. It had a conclusion, viz, what accomplished photographers were doing around the year 2000.

The current show, somewhat contradictory to its subtitle, does not have a similar ending. It is more retrospective than I anticipated. It is not necessarily about what Maine photographers are doing today, rather it includes work that they have produced at any time over the last 10 years. For the public at large, that’s not likely to be an issue. Good images are good whenever they have been made. For those viewers who follow the art, the show is apt to lack edge. They will find it too familiar. It is less interesting to revisit what an artist has done a few years ago than to see what that artist is doing today.

This is not just splitting hairs. The last decade has been tumultuous. Photographers with established aesthetic positions and great techniques have cast much of the past aside in favor of digital innovation. It would be interesting to see what the newfound freedom is doing to their art and, by the same token, their spirit. Thus far, digital has been a leveler. How are the photographers that I have so admired faring? Are they keeping true to the faith? Are they making digital simulations of their past attitudes? Are they reborn?

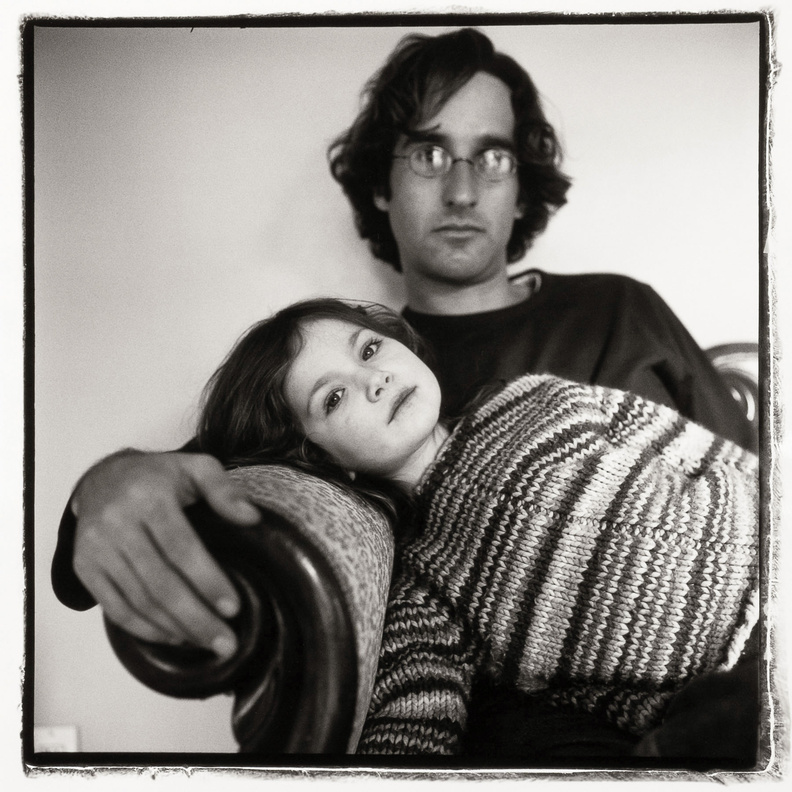

Selecting images to discuss from so large and diverse a show is almost pointless, but I allow myself the luxury of calling attention to a few. Denise Froehlich’s dual portrait “Zoe and Ian, Kennebunkport, Maine” will melt your heart. Michael Grillo’s “79 Maple Street” — a boy ascending a flight of stairs as shot through a toilet and above a long hall — is a masterpiece of wry composition. Cig Harvey’s “Emmie in Truck” is whimsical, touching and graphic. Diane Hudson’s color print of children banked up in a great hall is animated and limitless in opportunities for individual examination. Kris Larson’s portrait of Wayne Robinson amid a pile of detritus embodies the authority and strength of the sitter. Bob Brook’s studies of the skulls of an owl and a raven scrapes up the fright and mystery of those creatures and the spooky intricacies of their crania. One of my favorites is Rene Braun’s portrait “Thomas.” I seldom see images that are so unguarded and compelling. I also note Dana Strout’s “Bucksport Bridge” which, in this case, is Bernd and Hilla Becher brought to Maine.

The catalog to the show is a little wonder and a source document for a long view of the decade.

THE ANCIENT LOCALES OF IRELAND

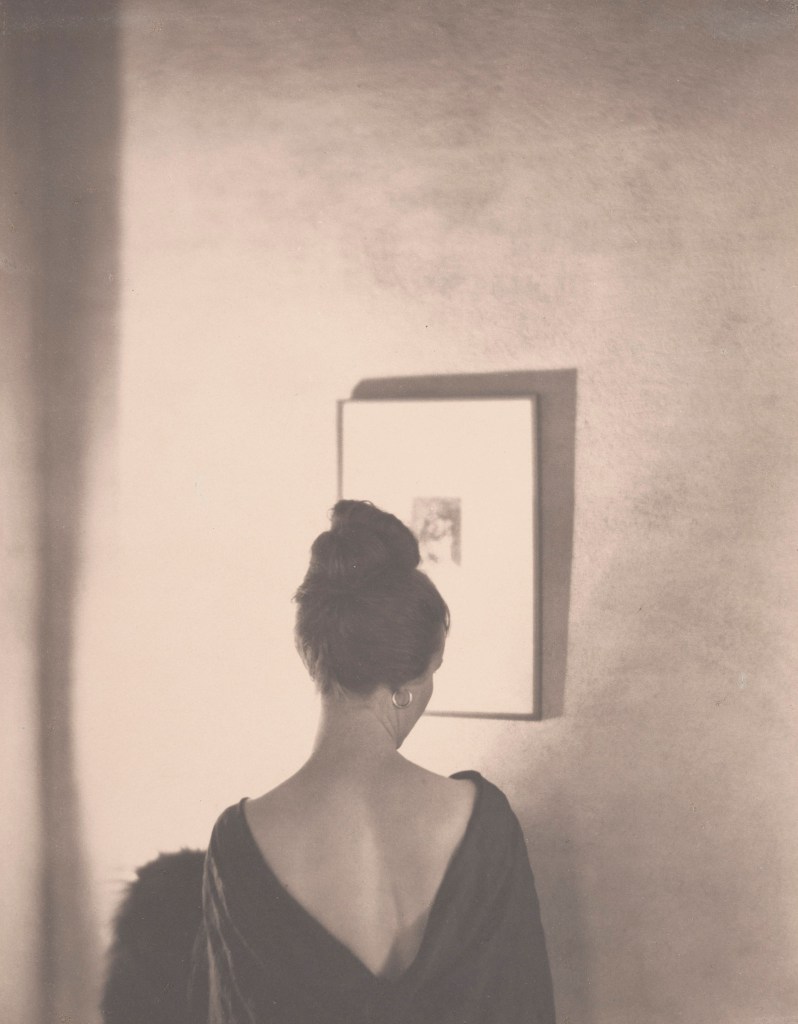

Addison Wooley Gallery’s show of Dan Dow’s photographs of ancient locales in Ireland is particularly interesting. Mr. Dow is a classic, large format, black-and-white photographer. His images in this show reflect the attitudes that go with that. However, they are not silver gelatin prints. They are digitally achieved with an assurance by the photographer that in doing so he would not do anything with an image that he wouldn’t do in the darkroom. I find this comforting because I consider the darkroom, however generous to the skilled, to be a limiting factor. Thus, other than the lack of the surface brilliance then comes with silver gelatin, Mr. Dow’s prints are gorgeous and he has caught the elegiac quality of that land’s ancient appointments as profoundly and with as much fidelity as the most expectant viewer would demand. In these prints, the photographer is fully committed and his sense of the age and mystery of the forms is almost palpable. They haunt him.

It is more than just a matter of a hoary Celtic cross against the battling Irish sky. It is a sense of the dark finality of its goal (jail) yards, the lone elegies complete with ruined abbies and friaries and the insistence of its lichen-infected lithes. This show says finality in terms that will touch your heart.

F/64 SHOW IN PORTLAND

Now to the Portland Museum and Group f/64. The full name of the show is “Debating Modern Photography: The Triumph of Group f/64.” The show consists of 90 or so works achieved by 16 artists. A didactic event; it is intended to instruct the viewer as well as to provide delight. The instruction begins with a series of beautiful old images that depict the aesthetic goals of photographers who flourished from, say, the 1890s into the 1930s. Those goals, in other hands, actually extended into the 1950s and those who held them over all those years are now called Pictorialists. They were challenged by paintings and sought to emulate the soft, romantic results they saw in them. Achieving those results required a considerable amount of manipulation in the darkroom.

The instruction continues with photographers who succeeded the Pictorialists and pretty much speak for present attitudes. Their work is for convenience classed as straight photography. The term f/64 originally referred to the aperture opening the early proponents of straight photography used in their large cameras. Stopped down to f/64, a camera yields extremely sharp, beautifully detailed images throughout their depth, the antithesis of Pictorial and, so they say, with little darkroom adjusting.

So, it comes down to a matter of style; rich, manipulated romantic images for a time before photography was admitted to the fine arts versus precise camera-created images to suit a time in which technology has enlarged our sense of beauty. I was raised in the fading years of the Pictorial style and am easily moved by the romantic haziness its images often attained. In the PMA show, I note the beautiful pictorials of Johan Hagemeyer, William Mortenson and Karl Struss.

I am more moved, however, by straight photography, in part because of the tempo of our times, and in part by certain aesthetic distractions. In the Portland show, I was particularly taken by Willard Van Dyke’s “American Scene #3” of 1934, Peter Stackpole’s “My Shoes and The Tower Leg,” Ansel Adams’ “Factory Building, San Francisco” of 1932 and Sonya Noskowiak’s “Untitled,” a cityscape of San Francisco made in the 1930s.

This is a very useful and fine exhibition. Many of the major names in both areas are not present, but there is enough to make the necessary historical points.

I note that in comparison to current work, the prints in the show are quite small and require an adjustment in viewer attitude; perhaps a mindset something like that brought to engravings and etchings.

It’s a little wearying, but worth it.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 45 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.