“There’s a hot wind blowing from the east,” Scottish author John Buchan wrote in his Middle East novel, “Greenmantle,” “and the dry grasses wait the spark.”

Those words, written almost a century ago, could apply to the U.S. position in the region today. Turbulent winds are blowing through the Arab world and American-backed houses of cards may fall.

It’s first, to be sure, a Middle East problem. In Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan, Yemen, and perhaps elsewhere, an opposition both young and old, secular, nationalist and Islamist, wants better governance, accountability, economic justice and human rights. But the United States and its interests will not be untouched by the storm.

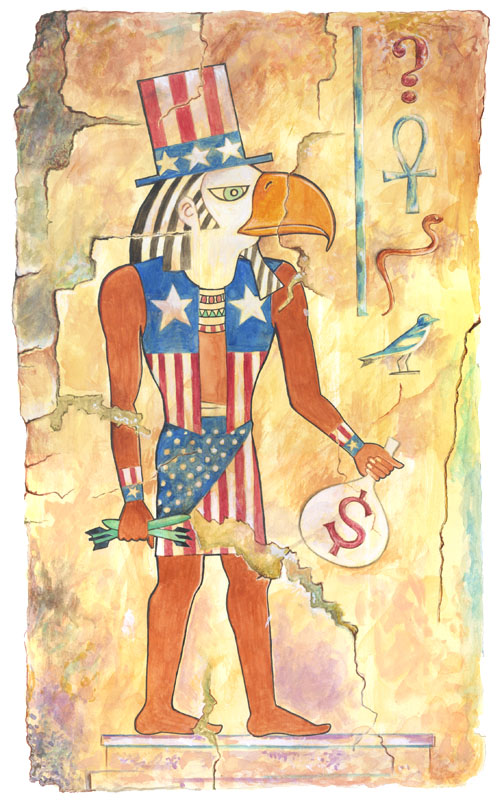

For 40 years, with the best of motives, averting radicalism, making peace, fighting terror, bucking up moderate governments, the U.S. has cut deals with authoritarian regimes that abused human rights and denied their public a free press and open politics. Some, like the Shah of Iran and Iraq’s Saddam Hussein (whom we supported in the 1980s), were worse than others.

Former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who was forced out and resigned Friday, isn’t Saddam or Slobodan Milosevic; he’s not a mass murderer, sociopath, or criminal.

He was a close friend and ally to the U.S. ever since President Anwar Sadat’s assassination in 1981. The U.S. built its Mideast policy around him.

In the 20 years I spent traveling with half a dozen U.S. secretaries of State, Cairo was always our first stop to coordinate with Mubarak.

The problem was that our interests and his method of governance were at odds.

The democracy movement is underestimating just how powerful the armed forces remain in Egypt’s governance. Egypt is likely to remain a praetorian state with the military still dominant in its political and security life.

But there will be change, most likely for the better. More openness, respect for human rights, less arbitrary practices by security services, and a more robust parliament and a freer opposition.

For Egypt, its people and politics, this will be good; for the U.S. it will be good too; but it will also be complicated and not quite so salutary for our interests.

Our challenge will flow not from the dire predictions that Islamic radicals will take over the country or that Egypt will close the canal, throw out U.S. companies, or abrogate the peace treaty. No, it will come from the very values of free expression, accountable and participatory government that Americans so cherish.

As the Egyptian political system opens up, government policies will need to reflect the sentiments of the public and, particularly, the elites, whether they are secular, Islamist or nationalist. And these will invariably reflect attitudes much more critical of U.S. policies and Israel.

Muslim Brotherhood spokesmen have already called for submitting the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty to a referendum.

Looking across the range of U.S. interests, the shared political space between the two countries will narrow.

n Iran: Mubarak detested the Iranians. He sat next to Sadat when Khalid Islambouli sprayed them both with machine-gun fire. The mullahs named a street in Tehran in the assassin’s honor. The new Egyptian government won’t be as allergic to closer ties with Iran and may be less willing to back our containment policies.

n Counter-terrorism: The Muslim Brotherhood will prevent al-Qaida from establishing itself in Egypt. But that doesn’t mean the new Egypt will be so supportive of our war on terror or participate in our efforts to combat radical Islam politically.

n Gaza: Mubarak didn’t like Israeli practices there or much care for Hamas. The next Egyptian government, even though the military will want a big say, will be more supportive of Hamas, less caring about weapons smuggled into Gaza and more critical of Israeli policies.

n Peacemaking: Whatever or whoever follows Mubarak won’t repudiate the treaty with Israel. The military doesn’t want a war; and U.S. aid, which topped $1.5 billion last year, is too important.

But, unlike Mubarak, who met with Israeli prime ministers regularly, worked to defuse crises, supported the more moderate Palestinian Authority, and worked closely with U.S. presidents, the new Egyptian government will be less forthcoming and willing to criticize U.S.-Israeli relations.

That in turn will have a negative effect on how flexible the Israelis are prepared to be in future Arab-Israeli peacemaking.

“History, like nature,” U.S. novelist Robert Penn Warren wrote, “knows no jumps. Except backward, maybe.”

Political change in Egypt will be good for Egypt over history’s long arc. And maybe for the U.S., too. But for now, it’s going to be a roller-coaster ride.

Aaron David Miller, author of the forthcoming book, “Can America Have Another Great President?,” is a public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and has served as a Middle East negotiator in Republican and Democratic administrations.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.