NEW YORK – More openness in government. Lawmakers across the country, including the Republicans who took control in many states this year, say they want it. But a 50-state survey by The Associated Press has found that efforts to boost openness often are being thwarted by old patterns of secrecy.

The survey did find signs of progress in a number of states, especially in technological efforts to make much more information available online. But there also are restrictions being put in place for recent electronic trends, such as limits on access to officials’ text messages.

The AP analysis was done in conjunction with this year’s Sunshine Week, an annual initiative begun in 2002 to promote greater transparency in government. To observe Sunshine Week, which runs March 13-20, AP journalists in all 50 statehouses reported on both recent improvements and the obstacles that still exist in many places.

First, the positive: In Alabama, where Republicans won control of the Legislature for the first time in 136 years, lawmakers can no longer bring up budget votes without warning. And Budget Committee meetings are now streamed live online. In the past, legislative leaders typically wrote state budgets in private.

“The public and the press can know where the dollars are being spent and why they are being spent,” Republican House Budget Chairman Jay Love said of the new practices.

In Indiana, a new website pulls together budget data, spending reports and other financial information that had previously been spread across multiple sites. New Hampshire launched a website in December that gives the public a window on where the state’s money comes from and where it goes — with links to budget documents. The public can also look up the salaries of state employees.

But the openness often goes only so far. Secrecy still prevails in many states among lawmakers of both parties, especially on budget matters where competing interests with big money at stake jockey for advantage.

While political watchdogs in Utah have praised some of the state’s transparency efforts, a purely political problem remains: Republicans, who have more than a two-thirds majority in the House and Senate, negotiate the budget in private with almost no input from Democrats. The same goes for meetings between the governor and GOP leaders, which usually are unannounced and not open to the public.

In New York’s state capital, Albany, critics have compared the budget process to the old Soviet Politburo — but, some suggest, even more secretive and more in the red. Despite a reform bill that passed in 2009, legislative leaders still craft budget bills behind closed doors and send them out for quick votes. Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who rode to office vowing to reform state government, has focused more on ethics and lobbying reform than on transparency.

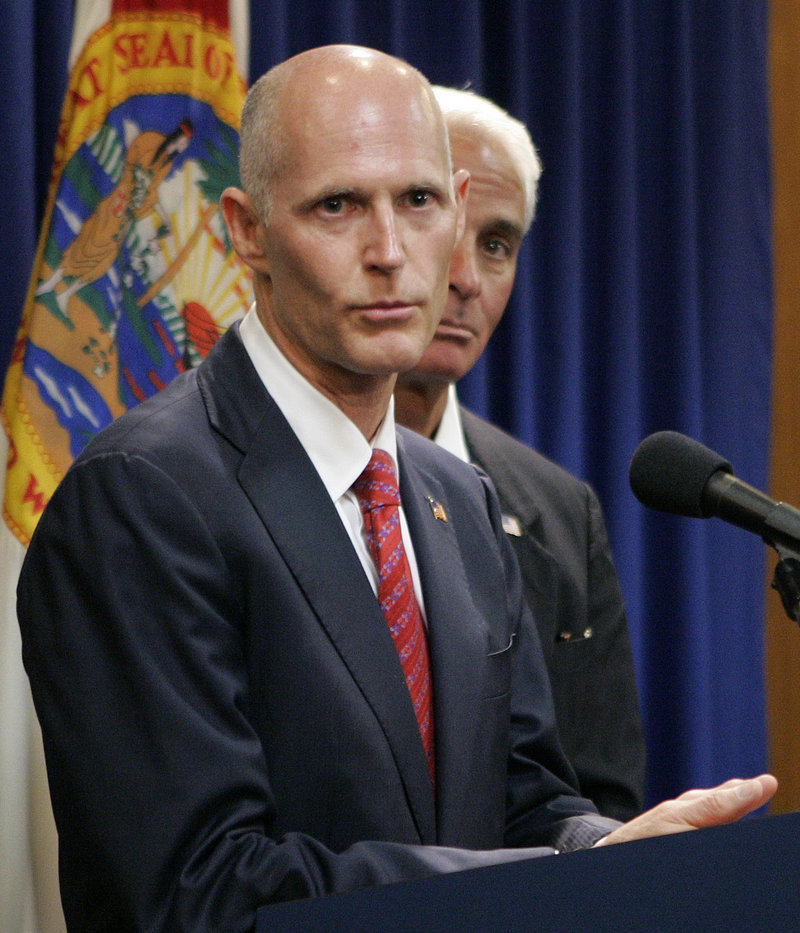

Florida Gov. Rick Scott has stepped back from his state’s generally strong record on transparency. His office has announced plans to charge a fee to fulfill open records requests, a practice allowed by state law but waived by the previous governor, Republican-turned-independent Charlie Crist. Scott’s spokesman said the decision was made to save taxpayer money, not to block access to information.

Even when there seems to be progress in some states, governors and legislators routinely exempt themselves from open records laws or defy them altogether.

Take Kentucky, where lawmakers long ago excluded themselves from the provisions of the open meeting law. They’ve used that exclusion to its fullest in recent budget talks, the AP found, closing themselves into legislative conference rooms with state police officers posted at the door as they figure out how to make up a $1.5 billion shortfall.

Or Nevada, a state where the Legislature is exempt from open meeting laws because it is not defined as a “public body” like local governments and agencies. While many budget discussions are carried out in public, the AP survey found most key details will be decided behind closed doors.

“Anytime you do that, go into a secret meeting, it makes the taxpayers wonder, ‘What are they saying that they’re afraid to tell us?’” said Barry Smith of the Nevada Press Association, which monitors lawmakers’ openness.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.