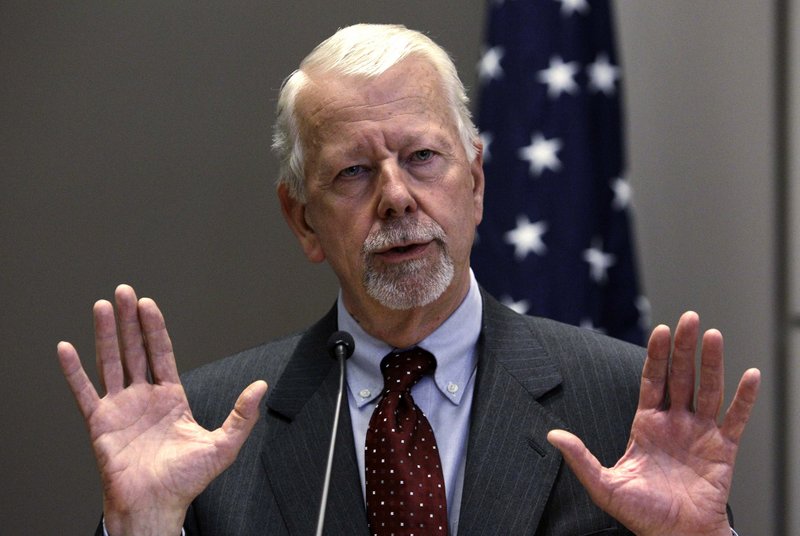

Shortly after he retired, the federal judge who struck down California’s voter-approved ban on same-sex marriage acknowledged publicly what had been rumored for months: He is gay and in a long-term relationship with another man.

Same-sex marriage opponents seized on Vaughn Walker’s revelation and filed a motion last week to have his ruling on Proposition 8 vacated, arguing that he could benefit personally from his decision if he wanted to marry his partner.

Although unusual, the effort could have legal merit, some experts say. If successful, it could mark the first time a judge has been disqualified or rebuked for issues related to his sexual orientation. And it would be a setback for gay rights groups, who view his opinion on Proposition 8 as one of their most significant victories in the quest for equal rights for same-sex couples.

While it is generally held that judges may not be removed because of their religion or minority status, experts say Proposition 8’s backers have come up with a novel strategy that reignites a complex, emotional debate.

In the 1960s and ’70s, many questioned whether female or black judges could fairly decide sex- or race-discrimination cases, said Stephen Gillers, a law professor at New York University who teaches legal ethics.

“Appellate courts quickly and correctly held that a judge’s sex and race have no bearing on the ability to decide cases impartially,” he said. “Now we’re seeing the issue arise based on sexual identity because the idea of a gay judge is, for many, new.”

As recently as 1998, an Asian American judge sanctioned two attorneys who asked that he be removed from a case in part because of his ethnicity.

In Walker’s case, those challenging his ruling say they are not taking issue with his sexual orientation, nor do they believe a gay person would be unfit to preside over the case. The issue, they say, is that Walker could directly benefit from his ruling and that he should have disclosed in court whether he intended to marry.

To many, no matter how nuanced the argument is, it amounts to one thing: an attempt to discredit a judge simply because he is gay.

“Would they try this with another judge in a different class? If the issue is equal pay for equal work, does it mean that no woman could hear that case?” said Tom Chiola, a retired circuit court judge and the first openly gay candidate elected to public office in Illinois. “Where does this line of argument end?”

Some legal experts downplay the likelihood that the challenge will succeed.

“It’s pretty well understood that status-based motions to disqualify are not going to float,” said Charles Geyh, Indiana University Law School professor and an expert on judicial ethics.

But the debate, he said, could have a chilling effect on other gay and lesbian judges who may be called upon to rule on same-sex marriage as the issue works its way through the courts. Already, more than a dozen lawsuits have been filed across the country challenging laws that limit the rights of gay couples to marry or qualify for benefits.

At the same time, the number of openly gay and lesbian judges has risen as the stigma fades and efforts continue to diversify the bench. Last month, Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick, a Democrat, nominated to the state’s high court a lesbian who legally married her partner. President Obama has nominated two openly gay men to the federal bench.

Judges have become increasingly open about their sexuality, but many remain quiet because they view it as a distraction in the courtroom, said Larnzell Martin, an officer of the International Association of Lesbian and Gay Judges, which has more than 85 members.

“There’s no judge, in my opinion, who does not [have] his own or her own biases or prejudices. We don’t judge in vacuums. We bring to the bench our experiences. We bring to the bench our sensitivity to certain things. We are allowed to have our leanings,” Martin said. “But we also bring to the bench a common training in the law.”

It had long been rumored that Walker, who was nominated to the federal bench by President George H.W. Bush in 1989, was gay. ProtectMarriage.com, the group defending Proposition 8, did not raise the issue during the trial but said it felt compelled to do so after Walker acknowledged his orientation to a Reuters reporter this year. In the interview, Walker said he never considered recusing himself.

Through a spokeswoman, Walker declined to comment this week. His ruling has been appealed, and the case is widely expected to be resolved by the U.S. Supreme Court.

ProtectMarriage.com, in its court filing, argues that Walker had a responsibility to disclose his relationship before the trial.

“It is important to emphasize at the outset that we are not suggesting that a gay or lesbian judge could not sit on this case,” the group’s attorneys said in their motion, which was submitted to the district court. “Rather, our submission is grounded in the fundamental principle, reiterated in the governing statute, that no judge ‘is permitted to try cases where he has an interest in the outcome.’“

Arthur Hellman, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh, called it a “very skillfully done document” because it ties in Walker’s own words from his ruling about marriage.

“He himself has said how beneficial marriage is, and having said all that, wouldn’t a reasonable person think that he would want to?” Hellman said.

But even those who say the argument has merit acknowledge that it may not be enough to persuade a judge to vacate Walker’s ruling. They say Proposition 8 proponents should have raised their concern earlier, when the rumors about Walker’s sexuality began to surface. And they point out that there is no evidence that Walker planned to marry his partner of 10 years.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.