A federal judge has ruled that former Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld can be sued personally for damages by a former U.S. military contractor who says he was tortured during a nine-month imprisonment in Iraq.

The lawsuit lays out a dramatic tale of the disappearance of the then-civilian contractor, an Army veteran in his 50s whose identity is being withheld from court filings for fear of retaliation. Attorneys for the man, who speaks five languages and worked as a translator for Marines collecting intelligence in Iraq, say he was abducted by the U.S. military and held without justification while his family knew nothing about his whereabouts or even whether he was still alive.

The government says he was suspected of helping pass classified information to the enemy and helping anti-coalition forces get into Iraq. But he was never charged with a crime, and he says he never broke the law and was risking his life to help his country.

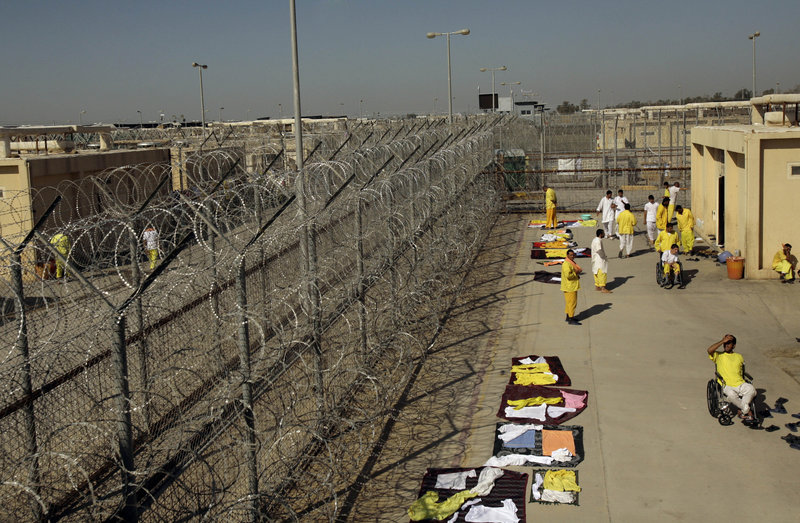

Court papers filed on his behalf say he was repeatedly abused while being held at Camp Cropper, a U.S. military facility near the Baghdad airport dedicated to holding “high-value” detainees, then suddenly released without explanation in August 2006. Two years later he filed suit in U.S. District Court in Washington, arguing that Rumsfeld personally approved torturous interrogation techniques on a case-by-case basis and controlled his detention without access to courts in violation of his constitutional rights.

Chicago attorney Mike Kanovitz, who is representing the plaintiff, says it appears the military wanted to keep his client behind bars so he couldn’t tell anyone about an important contact he made with a leading sheik while helping collect intelligence in Iraq.

“The U.S. government wasn’t ready for the rest of the world to know about it, so they basically put him on ice,” Kanovitz said in a telephone interview. “If you’ve got unchecked power over the citizens, why not use it?”

The Obama administration has represented Rumsfeld through the Justice Department and argued that the former defense secretary cannot be sued personally for official conduct. The Justice Department also argued that a judge cannot review wartime decisions that are the constitutional responsibility of Congress and the president.

But U.S. District Judge James Gwin rejected those arguments and said U.S. citizens are protected by the Constitution at home or abroad during wartime.

“The court finds no convincing reason that United States citizens in Iraq should or must lose previously declared substantive due process protections during prolonged detention in a conflict zone abroad,” Gwin wrote in a ruling issued Tuesday. “The stakes in holding detainees at Camp Cropper may have been high, but one purpose of the constitutional limitations on interrogation techniques and conditions of confinement even domestically is to strike a balance between government objectives and individual rights even when the stakes are high.”

In May, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that Attorney General John Ashcroft could not be personally sued for adopting a policy that led to the arrest and 16-day detention of an American Muslim who was never charged with a crime. The court sets a high bar for suing high-ranking officials, requiring that they be tied directly to a violation of constitutional rights and must have clearly understood that their actions crossed that line.

The case before Gwin — John Doe vs. Donald Rumsfeld — involves a man who went to Iraq in December 2004 to work with an American-owned defense contracting firm. Both sides agree he was assigned to work as an Arabic translator for Marines gathering intelligence in volatile Anbar Province along the Syrian border.

He says he was the first American to open direct talks with Abdul-Sattar Abu Risha, who became an important U.S. ally and later led a revolt of Sunni sheiks against al-Qaida before being killed by a bomb.

In November 2005, the translator was scheduled to fly to the United States for annual leave when Navy Criminal Investigative Service agents questioned him about his work, refusing his requests for representation by his employer, the Marines or an attorney. Documents filed by the Justice Department say he was told that he was suspected of helping provide classified information to the enemy and helping anti-coalition forces attempting to cross from Syria to Iraq.

He says he refused to answer questions because of concern about confidentiality, and the agents handcuffed and blindfolded him, kicked him in the back and threatened to shoot him if he tried to escape. Both sides say he was then transferred to an unidentified location for three days before being flown to Camp Cropper.

For his first three months at Camp Cropper, he says he was held incommunicado in solitary confinement with a hole in the ground for a toilet, only rarely allowed short trips outside in the middle of the night. He says he was then moved to cells holding terrorist suspects hostile to the U.S. who were told about his work for the military, leading to physical attacks by his cellmates that left him in constant fear for his life.

His lawsuit claims guards tortured him by repeatedly choking him, exposing him to extreme cold and continuous artificial light, blindfolding and hooding him, waking him by banging on a door or slamming a window when he tried to sleep, and blasting heavy metal or country music into his cell at “intolerably loud volumes.”

The plaintiff says he always denied any wrongdoing and truthfully answered questions, but interrogators continued to threaten him and accuse him of lying. Both sides say a Detainee Status Board in December 2005 determined he was a threat to the multinational forces in Iraq and authorized his continued detention, but he says he was not allowed to see most of the evidence against him and the documents the government filed with the court only say he is suspected of a crime, without providing details.

He says a month after a second Detainee Status Board hearing in July 2006, he was shackled and blindfolded and put on a military flight to Jordan with a new U.S. passport. He then returned to the United States.

He says his personal property was never returned and he was placed on a “black list” that prevents U.S. military contracting firms from hiring him.

The Justice Department declined to comment on the case.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.