Nobody yelled at the president. When you control the House of Representatives, maybe you don’t have to.

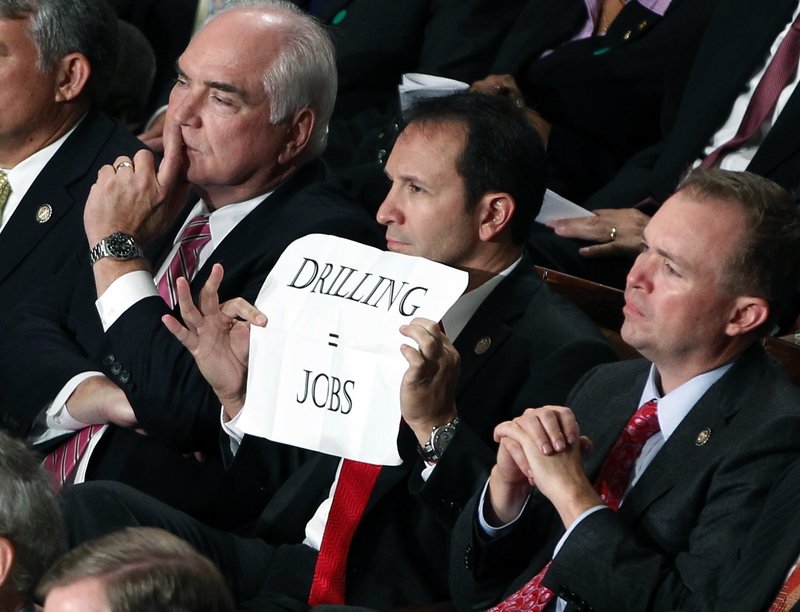

On the right side of the House chamber Thursday night, the House Republican majority sat silent through much of President Barack Obama’s jobs address. They clapped for veterans getting jobs. They laughed when Obama said his ideas weren’t “political grandstanding.”

But mostly they sat.

They sat while Obama got standing ovations from the left side of the chamber about protecting collective bargaining rights. Sat while he characterized a GOP push to cut regulations as a “race to the bottom.” Sat while Obama said of his jobs bill, “You should pass it right away.”

Thursday night’s speech was a restaging of a familiar Washington ritual, with an unfamiliar cast. There was a Democratic president trying to work with a divided Congress. And a Republican majority is trying to figure out how to dissent without being disruptive, or seeming disrespectful.

Going in, both sides said they wanted to find new ways to work together.

After a fiery speech to a stone-faced GOP audience, it appeared they would go on looking.

“The president had some good ideas. I think he missed a lot of opportunities by writing people off” by characterizing Republican positions unfairly, said Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif. “It was not as good a speech as I’d hoped it would be, but some of the elements give us a starting place.”

The speech came at a sensitive time for both Obama and the House GOP: Both had been stung by the perception that they are more interested in political warfare than real-world solutions. House Republican leaders seemed to be taking a different tack than the top Republican in the Senate, Minority Leader Mitch McConnnell of Kentucky.

On Thursday, McConnell bashed Obama for a speech he hadn’t given yet. “This isn’t a jobs plan; it’s a re-election plan,” he said on the Senate floor.

But in the House, whose leaders had pushed Democrats to the brink of a government shutdown and a national default earlier this year, top Republicans said they were seeking common ground. In a closed-door meeting, they asked rank and file Republicans to show Obama respect.

“I’ve got 434 colleagues who have their own opinions and they’re entitled to them,” House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, told reporters afterward. “But as an institution, the president is coming at our invitation. We ought to be respectful and we ought to welcome him.”

Presidential addresses to Congress are fraught moments of political intimacy. People who have spent careers criticizing one another in absentia are suddenly face to face. Then, they are subjected to an elaborate ritual of welcomes and thank-yous and my-fellow-Americans that is designed to keep them quiet.

“There’s plenty of places for shouting matches . . . but once you’re in that chamber, there should be decorum,” said Raymond Smock, the House’s former historian. Smock remembered some presidential addresses, decades in the past, when speakers were so worried about appearances that they used staffers to fill empty seats.

In these meetings, the traditional method for expressing dissent is to sit, silent, when the other side gets up to applaud a partisan point.

But, in recent years, some legislators haven’t been satisfied with silence. In the 1990s, President Bill Clinton heard hisses when he put down a balanced-budget amendment favored by Republicans. In 2005, President George W. Bush heard catcalls from Democrats when he talked about overhauling Social Security.

And, in 2009, Rep. Joe Wilson, R-S.C., yelled “You lie!” at Obama as the president gave an address to Congress on health care.

Afterward, many Republicans said they were surprised at the aggressive tone that Obama chose.

Senate Republican leaders viewed the speech as the most defiant he’s delivered to a joint session of Congress, his fifth in the last 2 1/2 years.

“It was designed to prove to his base that he’s a strong leader,” Sen. John Thune, R-S.D., the No. 4 GOP leader, said afterward. “He projected an intensity we haven’t seen in previous speeches.”

The Republicans who had put so much thought into how to be an audience discovered that they might not have been Obama’s audience after all.

“I really feel like it was an aggressive tone,” Rep. Adam Kinzinger, R-Ill., a freshman, said afterward.

“He was out there saying ‘Pass the bill,’ before he began discussing what was in the bill,” Kinzinger said. “And you had half of Congress get up and clap. . . . It was a little bit of a fighting speech.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.