WASHINGTON – The leading safety-net program for America’s disabled workers is in a financial death spiral in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

The sour economy, weak eligibility standards and a wave of aging baby boomers are driving an explosive increase in the number of injured workers who get disability benefits through the Social Security Disability Insurance program.

At the current growth rate, the SSDI trust fund, which pays for benefits, won’t have enough money to meet its obligations in 2018.

In September, SSDI paid nearly 8.5 million injured workers an average of $1,070 per month. That’s up nearly 20 percent from 7.1 million when the recession began in December 2007. There were only about 3 million recipients in September 1990.

Roughly half of all applicants eventually get accepted into the program, and fewer than 1 percent ever return to work.

Among new program enrollees in 2010, more than half cited back pain or mental problems, like depression or other mood disorders, as their disabling injury, compared with just 26 percent of such claims in 1965.

Both ailments are among the hardest to evaluate medically, which opens the door for potential fraud — both in program applications and during appeal hearings, where 60 percent of previous benefit denials are reversed.

Mismanagement is also a problem. A 2010 investigation by the Government Accountability Office found thousands of cases in which private-sector workers and federal employees in the program may have received improper benefits, or violated program rules on the amount of work allowable in order to continue receiving benefits.

The Social Security Administration disputed the GAO report, but experts say it’s past time to tighten program management and overhaul SSDI’s eligibility standards, its appeal process for benefit denials and the incentives that drive injured people to leave the work force and seek disability status.

“This is not a disability crisis in the sense that suddenly our workers are becoming less healthy,” said Richard Burkhauser, professor of policy analysis and management at Cornell University.

“This is a fundamental flaw in the system that leads us to increasingly use SSDI as a long-term unemployment program for people who could be in the work force if they had the appropriate (workplace) accommodations and rehabilitation.”

Between 1989 and 2009, the share of working-age Americans with SSDI benefits doubled to 4.6 percent, while benefit payments tripled to $120 billion over the same period. Yet the number of SSA disability reviews to determine if longtime recipients still meet program medical standards has fallen precipitously.

Burkhauser, who has co-authored a new book on the troubled program, said new SSDI enrollment could shrink by 25 percent or more if employers had an incentive to help their injured workers return to work. The SSDI trust fund is supported through payroll taxes on employers and eligible workers.

“I’m for reducing payroll taxes of employers who have better records of helping their workers not to come onto the SSDI rolls and increasing the payroll tax on those who don’t,” Burkhauser said.

The same reform helped the Netherlands cut the share of workers who receive disability benefits by one-third since 1980.

“And they did it, not by kicking people off the rolls, but by slowing down the movement of people who come onto the rolls.” Burkhauser said.

Unlike worker’s compensation, which partially replaces wages for workers injured on the job, SSDI goes to eligible workers even if their disabling ailment wasn’t caused by a work-related incident.

But employers are more likely to help rehabilitate a worker who was injured on the job because the company will face higher insurance premiums if that employee files for worker’s compensation.

No such incentive exists for employers in the SSDI program. They all pay the same 1.8 percent SSDI payroll tax regardless of how many of their employees are in the program.

David Autor, an economist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has also called for adopting the Dutch approach. He said the SSDI program simply isn’t set up to help disabled people work.

“It’s basically, ‘Prove to us that you can’t work, so you can get some help.’ So it’s a death knell for anyone’s future in the labor force,” Autor said.

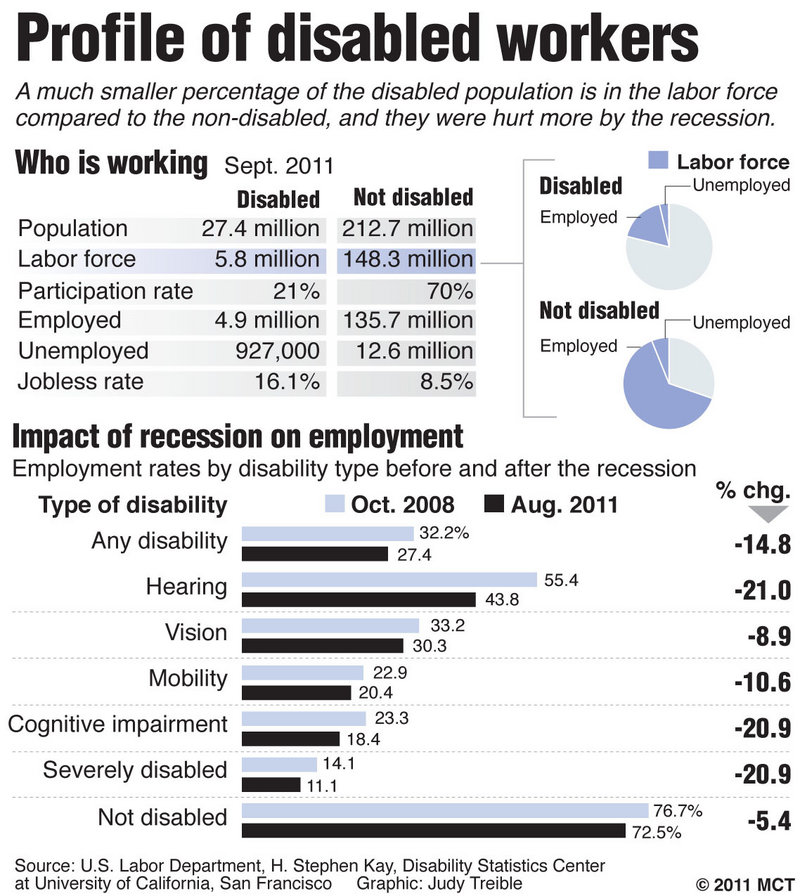

Increasingly, jobless disabled workers are winding up on SSDI. When they lose jobs, disabled workers typically look for other employment because it pays more than SSDI benefits, said Social Security Administration spokesman Mark Hinkle. But in economic slumps, the program sees a rise in applications when work opportunities dry up.

The wave of baby boomers hitting their disability-prone years is also fueling the enrollment surge. So is the growth of the working-age population and more females in the labor force, said David Stapleton, who directs the Center for Studying Disability Policy at Mathematica Policy Research, a social research organization based in Princeton, N.J.

Said Richard Pierce, a law professor at George Washington University: “Imagine some poor guy out of work for two years,” Pierce said. “Almost certainly he’s both anxious and depressed. He’s also desperate, and that’s what a lot of these cases are about. … ‘I’m giving up. I’m just going to file for permanent disability status.’

“There may be some fraud in there, but I think that’s a small part of the story. I don’t think it’s the core of the problem.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.