In a recent interview with me, Jamie Wyeth talked about painting as a struggle that, for him, is “not particularly enjoyable” until, after so much work, “that certain moment when it comes alive.”

This might sound a bit odd in light of Wyeth’s facility and incredible chops, but it seems reasonable enough considering his work is representational and tends to feature animals and/or people.

Yet I think Wyeth was talking about something much more fundamental than canny depictions of living creatures — the fleeting “thing” of alchemical, spiritual or even Faustian potential that has made painting the virtual religion of so many artists and art lovers over centuries.

The understanding of this “thing” exploded with the birth of abstraction, which first appeared in our culture with spiritual explanations.

Many of the earliest abstract painters were deeply mystical (Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich, Delaunay, Kupka, etc.), and the fact that abstraction erupted rather simultaneously throughout Europe makes it seem more about the zeitgeist than any individual discovery or invention.

If you’re not exactly sure what I mean by this “thing,” go see Harry Nadler’s paintings at Elizabeth Moss Gallery.

While it usually takes a little while to get a feel for what is going on in abstract paintings, every once in a while they hit you with all the subtlety of a speeding train — which is what happened to me when I stepped into the gallery and found myself facing “Sea Rhythm 4” (1977).

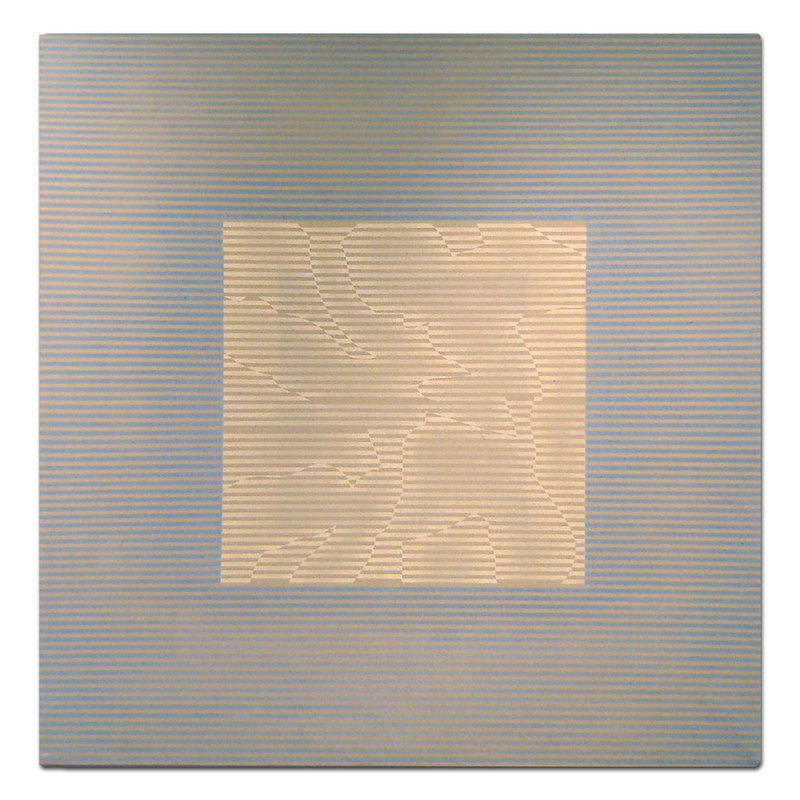

The piece is a 60-inch square canvas hung like a diamond that pulses with swimming blue and gray forms echoing the geometry of the format deeper and deeper into the middle of the canvas.

It’s a phenomenal painting in formal terms: the tones and handling of the paint, the interweaving of the wave-like forms into the geometrical lattices, the relation of detail to the whole, the tiny pencil marks that insist on a diagonal logic, are all beautifully handled.

But “Sea Rhythm 4” quivers with something palpable and undeniable — that “thing.”

The power of art (just like religion) is often the ability to conjure the ineffable. We tend to think of this power — the numinous — as spiritual or religious, but experiencing it doesn’t require any kind of faith whatsoever, which is probably why the church historically sought to maintain absolute control over art and music and the way we have talked about them for centuries.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence abstraction appeared as ecclesiastical cultural hegemony waned.

While it’s painful to see so many powerful Nadler paintings crammed into such a small gallery, it makes you appreciate their strength. Nadler might deserve more (and more vaunted) space, but I commend Moss for bringing this work to Maine.

Most of Nadler’s paintings in the show follow a strong linear and geometrical logic. They also proudly announce their reverence for Mondrian, Matisse, Cezanne and many other great modern painters.

Some are extremely elegant and subtle, such as the minimally horizontal graphite lines on the large white “Amagansett #2” (1974). Others, such as “Inscape #8” (1979), feature labyrinthian complexity with jaunty, cubist overtones.

The most substantial group of works, however, relies on the golden ratio and golden rectangles. These works start with a Euclidian framework and take off step by diagonal step on their own geometrical narratives as though drawn by some process of folding in on themselves.

Yet Nadler mirrors the seemingly arbitrary linear narratives across a diagonal axis so they attain a subtle symmetry that is easy to miss despite his reinforcing the bilateral symmetry with bold, Matisse-like colors.

While nothing in the show can match the elegance of the gorgeously striated “Night Window #5” (1974) with its mysteriously roiling interior square, my favorite painting in the show is the very large (72 by 84 inches) “White Series #5” (1972). In this piece, Nadler presents a grid of 42 square cells with biomorphic forms barely visible in four shades of white.

The forms look like details of female figures from Matisse cutouts, especially with their stencil-like edges among the layers of paint. It is a quiet and deliciously calming painting.

I am not sure what to make of Lori Ingraham’s mixed-media leaf paintings in Moss’ front gallery. Up close, you can see the effort, skill and technique that go into them, but from any distance they start to look like bunches of leaves stuck to canvases — which is what they are.

One alone in a home might be gorgeous, but altogether they have too much of a factory effect. And it probably doesn’t help Ingraham to have been paired with a heavy hitter like Nadler.

Nadler’s work is brilliant, intense, self-aware and deeply in love with the culture of painting. (In fact, he once had several paintings celebrating Ingres in a show at the Louvre).

But above all, it’s got that “thing.”

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.