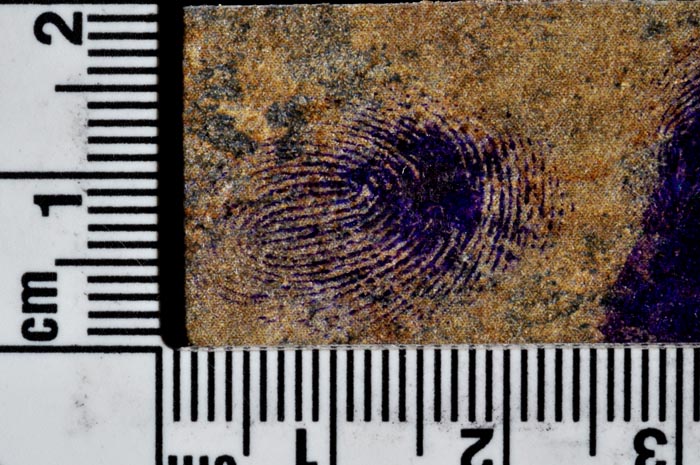

When Keith Cook lifted his first fingerprint as a Cumberland County sheriff’s deputy a decade ago from a window pushed open during a home burglary, he used his own kit composed of clear tape and index cards bought at Walmart along with standard-issue fingerprint powder.

Now enrolled at the National Forensic Academy at the University of Tennessee, Detective Cook is learning to use a magnetic wand and Sled Red powder, which glows under ultraviolet light, then digitally photograph the print so it can be uploaded to the Automated Fingerprint Identification System.

The technique enabled Cook and the other two dozen students to pull a usable print off a feather, something almost unheard of in old-school forensics.

At the university’s Law Enforcement Innovation Center, Cook is taking a 10-week class that covers a broad range of topics, including finding and recovering skeletal remains, blood spatter analysis and bullet trajectory calculations.

“There’s a lot of science behind the processes we use, and it’s all the scientific side of it I’m really most interested in,” said Cook, whose favorite subject at Mt. Ararat High School in Topsham was science.

Part of the forensics class is taught at the university’s Anthropological Research Facility, commonly called the “body farm,” where human remains that have been donated to science are buried or otherwise maintained at various stages of decomposition.

That’s where Cook and his fellow crime scene investigators recently were trained on techniques for finding and exhuming a body.

“They’ve got over 200 bodies at any given time at the research center, some above ground, below ground, hanging in trees, some sitting in chairs,” Cook said Monday. Instructors seek to replicate the circumstances police might encounter while investigating a possible homicide. Cook’s class was assigned to an open area and instructed in techniques to help locate a burial.

The students – from Alaska to Florida, small rural departments to the New Jersey State Police – scoured the ground looking for a depression in the earth and for variations in the color of dirt. Then they probed the area with fiberglass rods. As the rods plumbed down into the soil, a sensitive hand could feel variations in the density of the dirt, Cook said.

Areas of lighter density – indications of earth that had been shoveled out, then replaced – were flagged, and when the students stood back, the flags resembled an oval.

“We used trowels and scraped the dirt away millimeters at a time … and ultimately revealed our entire skeleton. The body had been in the ground around 2 years,” he said.

Once the skeleton was revealed, it was mapped, measured and photographed, then slowly extracted bone by bone, coming up short by only the bone of one finger, he said. It was frustrating, Cook said, because that bone could be the clue to how someone died.

It’s hard to anticipate when Cook’s training will be needed, but there is a good chance it will, said Sheriff Kevin Joyce.

“If he never has to use it, that’s fine,” Joyce said. “At some point, something is going to happen in our area that’s going to be closely related to what he’s been able to experience down there.”

The department spent $7,500 for the course, which also is subsidized by the federal Bureau of Justice Assistance. The advanced training will benefit the sheriff’s office and also could benefit local departments through collaborations that occur at the regional forensic lab housed at the Portland Police Department, Joyce said.

Cook also has been filing regular briefings with the department, some geared to the patrol deputy on the beat. An example related to a recent case involved carbon monoxide poisoning.

Investigators discovered high levels of carbon monoxide in a Raymond home where the bodies of an elderly couple were found last August, but the bodies lacked the telltale cherry-red skin pallor of a carbon monoxide poisoning. Cook learned, and related to the department in his weekly briefing notes, that someone can die from extremely high levels of carbon monoxide before enough is inhaled to infuse the bloodstream.

That can be important, both in investigating a death in such circumstances, and in being aware of the hazard that carbon monoxide can pose to the first deputy on the scene.

Cook said he has enjoyed the class, but it is a lot of work – more than his usual job of detective.

“I’ve done nothing but study nonstop,” he said. “It’s not just class time. We work nights and weekends doing homework and research projects. It’s definitely not been a vacation.”

Staff Writer David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

dhench@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.