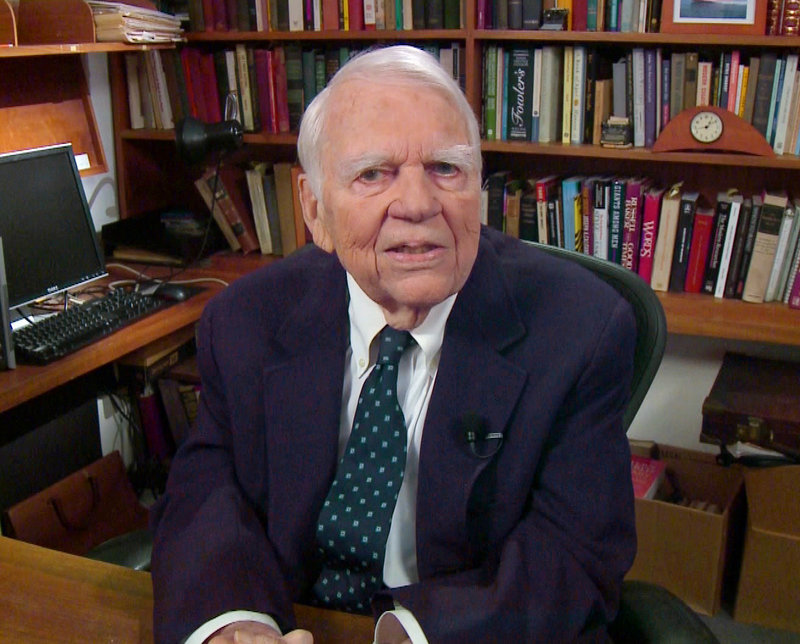

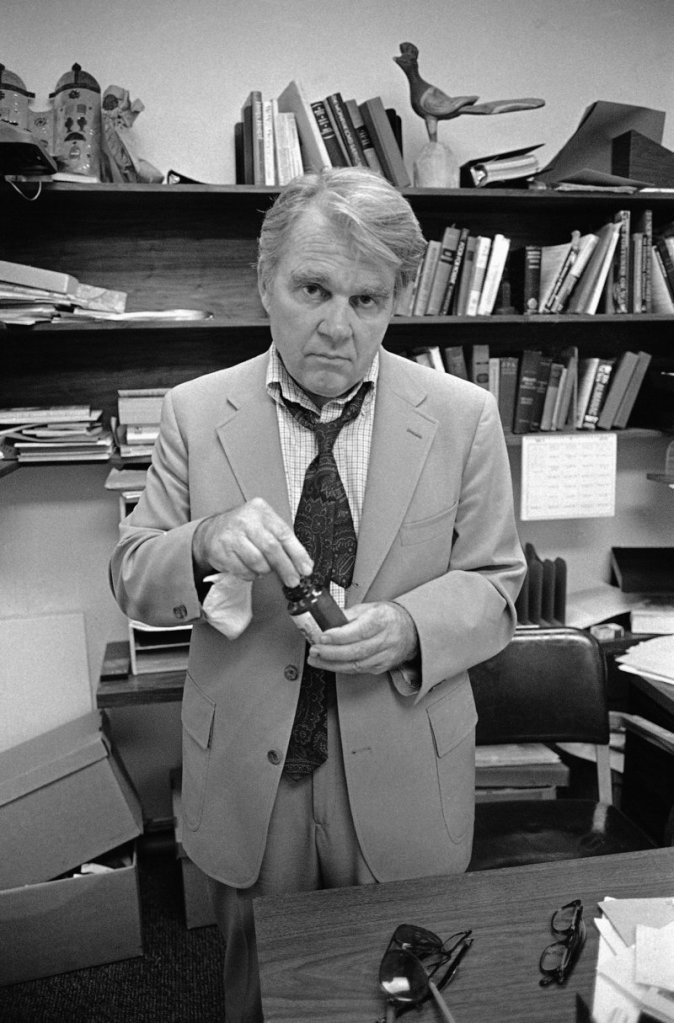

Andy Rooney, a humorist whose deadpan wit, perpetually furrowed brow and insights on the illogic and quirkiness of modern living defined his long-running commentary segment on CBS’s weekly news program “60 Minutes,” died Friday night in New York. He was 92.

The death, nearly five weeks after announcing in late September that he was ending his regular appearances on “60 Minutes,” was confirmed by CBS.

Rooney was a best-selling author and syndicated columnist but was best known for his long and celebrated career as a television essayist. The late CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite once described Rooney as an “Everyman, articulating all the frustrations with modern life that the rest of us Everymen (and Everywomen) suffer with silence or mumbled oaths.”

His three-minute segments on “60 Minutes,” which typically closed the program, brought him national recognition as the quintessential curmudgeon. For more than 30 years, he lent his exasperated take on whimsical topics, including the uselessness of the cotton insert in a bottle of pills and the sense of frustration when winter gloves go missing.

In a piece about office clutter, he sat at his desk and asked, “What’s a paperweight for, anyway? Papers don’t blow around in here. I can’t even open the window, what do I need to weigh papers down for?”

Rooney endeared himself to fans by being frank and down-to-earth, as in a 2008 piece about his distaste for modern art and its prevalence in public spaces. “When did bright-colored plastic cows, pigs and rabbits get to be art?” he began.

He called one New York street sculpture called “Two Indeterminate Lines” “pretentious nonsense” and went on to note, “Does every open space have to be filled in? Is this really better looking than nothing would be? I don’t think so.”

Rooney occasionally weighed in on more serious topics, such as a 2003 segment about the war in Iraq.

“We didn’t shock them and we didn’t awe them in Baghdad,” Rooney said less than two weeks after the war began, citing a slogan used by the Bush administration to promote the invasion. “The phrase makes us look like foolish braggarts. The president ought to fire whoever wrote that for him.”

He said later in the same essay, “I wish my America had never gotten into this war. Now that we’re in it, I want us to win it.”

No matter the subject, his television essays always served as a cultural touchstone. “In so many of his commentaries, he sort of encapsulates all of the changes that occurred in America during and after World War II,” said Ron Simon, a curator at the Paley Center for Media in New York.

Rooney, Simon said, “is like the grandfather who remembers life without television.”

Rooney, a reporter for the Stars and Stripes newspaper during World War II, had worked at CBS for almost 30 years before joining “60 Minutes.” He joined the network in 1949 as a writer for “Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts” and went on to write for “The Garry Moore Show” and various public affairs programs

In 1964, he began a celebrated collaboration with CBS correspondent Harry Reasoner on a series of television specials, including “An Essay on Doors” (1964), “An Essay on Hotels” (1966), “An Essay on Women” (1967) and “An Essay on Chairs” (1968), among others.

Rooney worked with Bill Cosby on CBS News’s “Of Black America” (1968) series, a project that focused on how blacks were portrayed in history books and Hollywood. His script for one installment, “Black History: Lost, Stolen or Strayed,” earned an Emmy Award.

In 1970, when CBS refused to air another of his specials, “An Essay on War,” Rooney quit the network. Executives told him they thought the piece was too long, but they also may have been worried about the fact that it expressed too boldly his doubts about the government’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

“A younger generation doesn’t understand why the United States went into Vietnam,” wrote Rooney, who had served in World War II. “Having gotten into the war, all it wanted to consider itself a winner was to get out. Unable to make things the way it wanted them, but unwilling to accept defeat, it merely changed what it wanted.”

He then took a job at PBS, where the piece eventually aired. He later worked at ABC before returning to CBS in 1972.

While his grouchy, acerbic style was his signature, it landed Rooney in trouble several times when his comments were perceived as insensitive or bigoted.

The most prominent example was when he was suspended from “60 Minutes” in 1990 after the Advocate, a national gay newspaper based in Los Angeles, quoted Rooney making derogatory comments about the intelligence of blacks.

Rooney denied that he had made the remarks and the Advocate had not recorded the conversation. The suspension from “60 Minutes” was supposed to last three months, but CBS cut that short after a dramatic drop in the show’s ratings.

Around the same time, Rooney drew fire from gay rights supporters after he wrote a syndicated column that said he “wouldn’t want to spend much time in a small room” with gay people, and then in a subsequent “60 Minutes” essay, likened “homosexual unions” to alcoholism and smoking, saying they were “self-induced” ills that could lead to early death.

Rooney’s career bounced back quickly after the brief rash of negative publicity. His memoir “My War” (1995) became a bestseller and he was given an Emmy lifetime achievement award in 2003. He received a prestigious Peabody Award for his hour-long CBS special “Mr. Rooney Goes to Washington” (1975), in which he professed to see “what a non-political reporter with no working knowledge of that place could find out about it.”

In interviews with an agency head who was at a loss to explain his purpose and some lavish soirees, he found a city not “being run by evil people, it’s being run by people like you and me. And you know how we have to be watched.”

Andrew Aitken Rooney was born Jan. 14, 1919, in Albany, N.Y. His father earned enough money as a salesman for Albany Felt company to send his son to private school.

He attended Colgate University in Hamilton, N.Y., before joining the Army during World War II. When he arrived in London, Rooney talked his way into a job with Stars and Stripes despite limited journalism experience; he had been a copy boy at an Albany newspaper.

In 1943, Rooney was one of a half dozen correspondents who flew with the Army Air Force on the first U.S. bombing raid against Germany. He was also among the first Americans to visit a German concentration camp. Rooney later co-wrote three books with Oram C. Hutton based on their wartime experiences, including “The Story of the Stars and Stripes.”

After his many postwar years at CBS, Rooney transitioned to the news division in 1964. His “60 Minutes” segment, “A Few Minutes With Andy Rooney,” launched in 1978 as a summer replacement for a partisan bickering feature called “Point-Counterpoint.” He soon replaced that feature.

Rooney’s pieces had a no-frills style: He was typically filmed sitting in his own office instead of a studio and the desk he sat behind is one that Rooney, an avid woodworker, carved and built himself.

As for the crabby disposition that has always been a hallmark of his style, Rooney told USA Today in 2010, “There’s an awful lot of nonsense in this world. I’m not shy about expressing a dislike when I feel it. If that’s grumpy, then I am.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.