Norton T. Dodge, a University of Maryland economics professor who during the Cold War amassed the world’s largest collection of Soviet dissident art, thereby preserving a record of artistic protest that otherwise might have been lost behind the Iron Curtain, died Nov. 5 at Washington Hospital Center in the District. He was 84.

He had congestive heart failure, said his wife, Nancy Dodge.

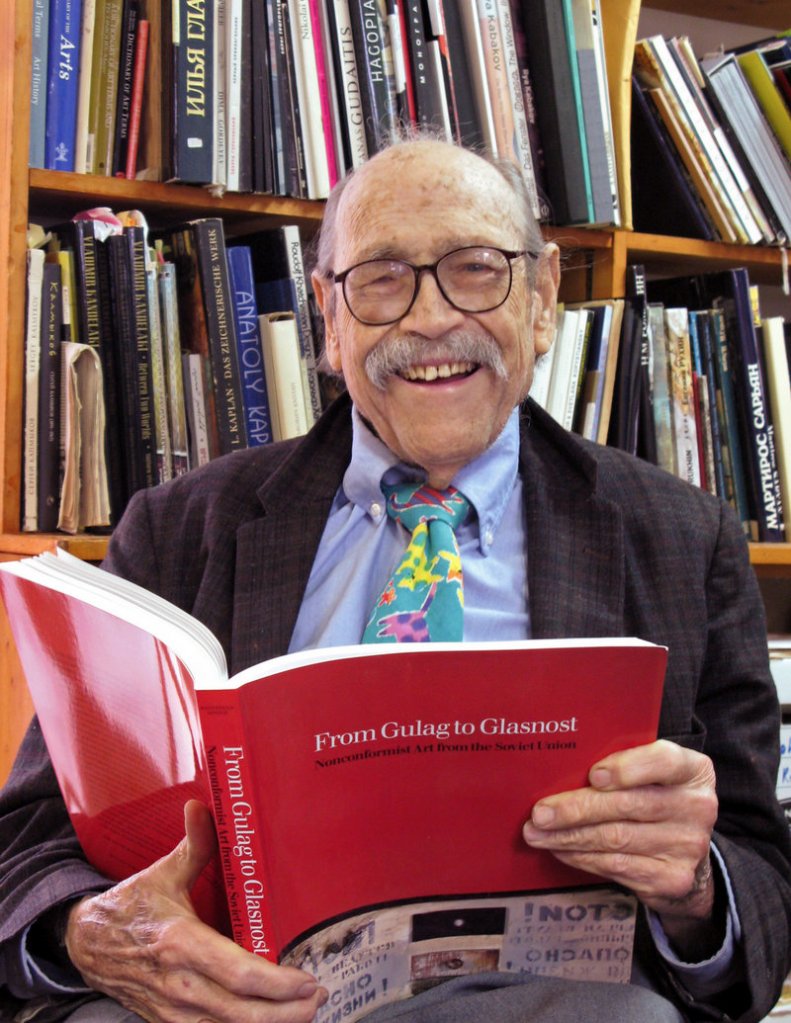

Dodge, an eccentric, somewhat disheveled man with a walrus mustache, was described in news reports over the years as an art smuggler and possible spy. To Dodge and his friends, that characterization was laughably off-base.

He spent decades, and a reported $3 million of his personal fortune, stockpiling thousands of pieces of “underground” Soviet art. The collection encompassed a swath of styles — abstract expressionism, images of nudity and religious iconography, dark satire — all made outside the state-sanctioned Socialist realism style. Many of the artists risked imprisonment, exile and even death.

“It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that Norton single-handedly saved contemporary Russian art from total oblivion,” Russian art critic Victor Tupitsyn told writer John McPhee, who chronicled Dodge’s story in a New Yorker article and the 1994 book “The Ransom of Russian Art.”

Dodge began traveling to the Soviet Union in the mid-1950s as a Harvard doctoral candidate studying the role of tractors in the Soviet economy. During his second visit, in 1962, he became friends with a student at a Moscow art institute. The man, disturbed by government restrictions on the students, introduced Dodge to the community of dissidents.

“Soviet nonconformist art expresses the power of the human spirit,” Dodge wrote in a catalog of his collection, which he and his wife donated in 1991 to the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. “I made it my mission to preserve . . . a sample of the best of this art.”

Dodge’s wealth — largely inherited from his father, who made a wise investment with a young Warren Buffett — allowed him to make himself the principal patron of underground art.

The artists Dodge supported included Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid, who parodied Soviet propaganda in the style of American pop artists. Dmitri Plavinsky flouted Communist dictates with overtly spiritual works. Boris Sveshnikov painted abstract portraits showing the shattered lives that came from Soviet prison camps.

Because of the danger the artists faced, Dodge revealed few details about the methods he used to build his collection. In part because of that reticence, his exploits were often described as worthy of a spy thriller. Dodge was depicted as meeting artists in dank apartments. He paid them in cash and sometimes with records, cameras and American-made bluejeans. Some accounts show him spiriting pieces out of the country in rolled carpets.

Dodge said that his work was far less dramatic than McPhee and others described. His wife said that most of the art arrived in the United States with suitcases bearing legal export stamps.

Dodge stopped visiting the Soviet Union after what he considered the suspicious death in 1976 of a friend, artist Evgeny Rukhin. Dodge told the Economist in 1998 that he assumed the KGB had set the fire that killed Rukhin in his Leningrad apartment.

After Rukhin’s death, Dodge continued working through the networks he had established there to bring art to the United States.

Before donating his trove to the Zimmerli museum, he housed the work in barns at Cremona Farm, his estate in Mechanicsville, Md. In 1995, The Washington Post reported that the collection was worth about $15 million. Today, it includes more than 17,000 works from the former Soviet Union.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.