It’s hard for us to believe sometimes that our parents had lives before they started having children.

Ann Boyce of Arundel had always known that her parents, Jean and Walt, had spent time in Afghanistan when they were in their 20s. But it wasn’t until Boyce started reading her mother’s 64-year-old diary entries and letters home that she truly began to understand her parents as flesh-and-blood people with an adventurous past.

One of her favorite discoveries was reading about her mother’s crush on an Indian journalist. The flirtation never led to a full-blown affair, but still provided plenty of shock value for a clueless daughter. When she read that her mother was traveling from Kabul to New Delhi “intending to commit adultery,” Boyce reacted by exclaiming, “Mother, you little hussy!”

“I wish I had known that woman, because she was such a live wire,” Boyce said. “She was so filled with life and wanting to understand people and wanting to experience everything, and I got a little bit of that. But the mother I knew, of course, was the mother of three small children and a faculty wife. I wish at some point that I could have gone back in time and met her at that time.”

Jean Boyce-Smith died in 2009, leaving behind a manuscript she had been working on about her life with Walt in Afghanistan. Ann Boyce, who teaches in the English department at Southern Maine Community College, decided to finish the book for her.

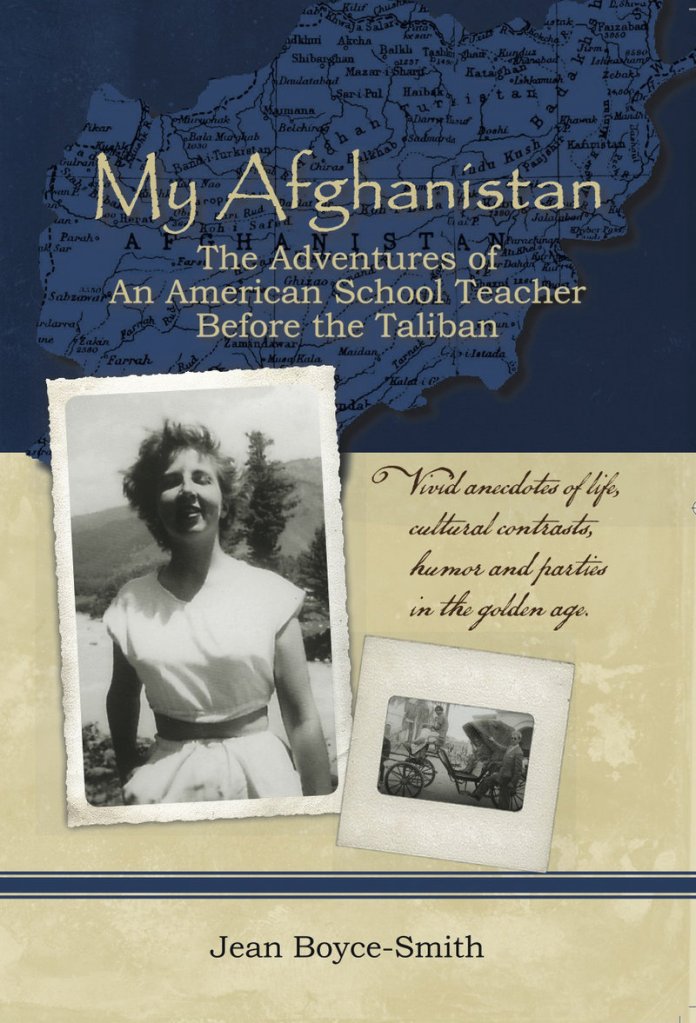

The result is “My Afghanistan: The Adventures of an American School Teacher Before the Taliban” (Aeronaut Press, $16.95). The book is available at Nonesuch Books in South Portland, at Kennebooks in Kennebunk, and through amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com.

Ann Boyce’s parents were just 22 in 1948 when they were recruited by the State Department and the Royal Afghan government to move to Afghanistan and teach. For more than a year, Jean Boyce-Smith taught male students, ranging in age from 13 to 23, at Habibia College in Kabul.

When the couple returned to the United States in 1950, they had every intention of continuing their adventures. Walt had been offered positions in India and Istanbul.

But they had their first child, and he accepted a position at Columbia University in New York instead. A year later, he was recruited to be the first dean of men at Bates College in Lewiston. Jean Boyce-Smith became an English teacher at Edward Little High School in Auburn.

Walt, who had struggled with depression his entire life, took his own life in 1968. Jean eventually remarried and moved to California.

Ann Boyce, 61, recently spoke with the Maine Sunday Telegram about her parents and what it was like to work on her mother’s memoir.

Q: Your mother worked on this book for 20 years. When did you first see it?

A: I first saw it after her death. She had actually shared a chapter with me at one point, about five years ago, I guess.

Q: So you knew she was working on it?

A: I knew she was working on it, yes. But how much she had done, that I didn’t know until after her death. And the fact that the letters had survived I didn’t know, and that she’d written a diary. Most of the information comes from the letters she wrote home to her mother, and she wrote anywhere from one or two a day to maybe two a week.

Q: Do you have a favorite story from the book?

A: Well, I’m actually relieved that the man she was going to see (in New Delhi) was in jail at the time. He was a journalist. I’m not sure I would have been here otherwise.

I think one of my favorite stories is one that she shared with me. They had just gotten to the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, and they were crossing in. This is actually when they were first coming into Afghanistan. And they’d been through all kinds of trials and tribulations on their way over. They were on a freighter that was carrying explosives, and she didn’t know until they were three days out of port.

All kinds of horror stories from the family in New England about going off to the land of the infidel and what was going to happen to them. Then they’d had this horrific car ride with a car that kept breaking down all through the Khyber Pass, and one of their fellow teachers had joined them and was filling them with horror stories about illness and problems.

So they get to the border, and all the men went into the border crossing to show them the visas and passports and whatever, and my mother was left out sitting by herself. And a Pathan tribesman approached her, and here is this very tall man, and he’s carrying a rifle. He’s wearing part of his turban over his mouth, (so) all she could see was his eyes.

And so here was this very tall tribesman with a rifle and a dagger approaching her, and she said all the horror stories that she’d been told about Westerners and about unveiled women flashed through her mind as she’s sitting there by herself.

Out of nowhere, from behind his back, he took out a bouquet of wildflowers and gave it to her. And she talks about the fact that she’s heard these stories of brutality, but everything she encountered in Afghanistan was summed up in that moment: Just this generosity, hospitality, kindness.

Q: Did she talk a lot about it when you were growing up?

A: Not really. I mean, we had things in the house that they brought back. We had a samovar. There was a lamp that came from the bazaar. There were earrings that she wore on occasion that were from Afghanistan. So there were these artifacts, but there weren’t a lot of stories told about that time, no.

Q: Your mother was only in Afghanistan for about a year, and one could certainly argue that it takes much longer than that to truly understand a different culture. Why do you think she became so captivated with the place?

A: I think it was a combination of this whirlwind social life that they led in the embassies and all the parties that they went to where they were on familiar terms with the ambassador from Iraq …

Yes, she was there for just a little over a year, but she taught, and she was working with Afghan boys who were fourth grade to just about high school. They brought their teachers into their homes so that she had an insight and a view of what home life was as well. Because she taught English, they wrote stories about their families and about the traditions.

There’s no question that she was in love with the people of that country and the incredible beauty of the country — the combination of the arid land and then these incredible lush valleys, the overwhelming beauty of the Hindu Kush. I think she felt people opened their hearts and their homes to her, and that was a very powerful experience.

Q: Did your mother closely follow political events in Afghanistan after she returned to the United States?

A: Yeah. One of the things that I discovered that my stepdad sent, was she had 20 years’ worth of clippings from various magazines and newspapers of what was happening in Afghanistan.

And the other thing is, they did — this was back in the days of the Russians — they did welcome Afghan freedom fighters into their home. Both of them were friends with the Afghan community in California up until the time of her death.

She had asked that her ashes be spread in Maine, in the Sierras in California, and in Afghanistan — which, you know, two years ago was a bit of a challenge. My stepdad was able to contact somebody who she referred to as her Afghan son, who is I believe was serving as a translator in Afghanistan, and sent him some of her ashes, and he spread them in Afghanistan by the side of a stream.

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MGoad@mainetoday

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.