Theodore Roosevelt busted trusts, charged up San Juan Hill and helped shape modern America. Along the way from Oyster Bay to Mount Rushmore, he also went looking for trouble.

In the 1890s, “New York reigned as the vice capital of the United States, dangling more opportunities for prostitution, gambling and all-night drinking than any other city in the United States,” writes Richard Zacks.

And Roosevelt was its vigorous, high-minded, infuriating, crusading police commissioner for two more-than-colorful years. It’s a period given comparatively little attention by his biographers. But his turbulent stint in that job presages the leader he’d become.

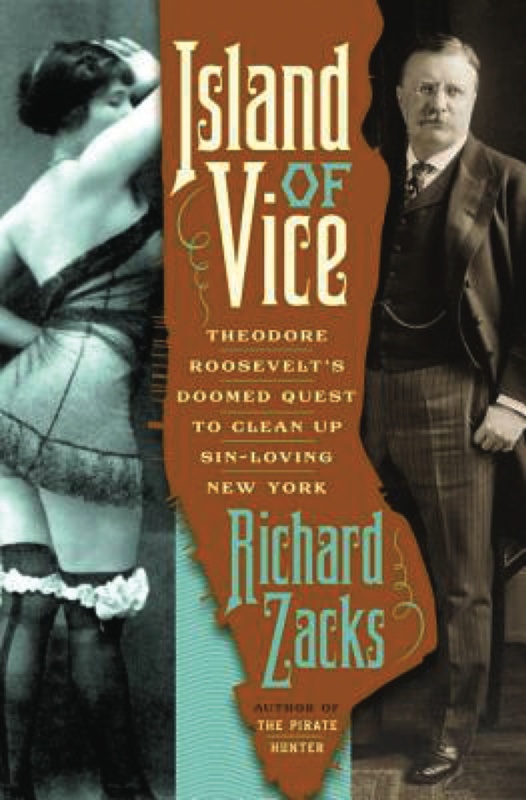

In “Island of Vice,” an entertaining, enlightening chronicle of New York City in that raucous, seedy decade, Zacks presents a cinematic saga about one of the reformer’s early battles: trying to clean up the city that definitely never sleeps. It was an era with symbols and realities far more dramatic than broken windows and squeegee men.

Zacks, author of “The Pirate Hunter” and “History Laid Bare,” tells a sharp, clear-eyed immorality tale, with cameo appearances by Stephen Crane, Lincoln Steffens, exotic dancer Little Egypt, plus a cast of real locals who’d have pleased Damon Runyon.

“Island of Vice” addresses the ongoing issue of policing morals. Overreaching was the inevitable outcome. The campaign exposed more hypocrisy and led to further lawbreaking.

New York was “a city of silk top-hats on Wall Street and 16-year-old prostitutes trawling Broadway,” Zacks writes, “of Metropolitan Opera divas performing Wagner and of harem-pantsed hoochie-coochie dancers grinding their hips on concert saloon stages.”

Yes, Fun City, 19th-century version.

Zacks evokes a New York where there was more horse theft than in all of California or Texas. More than 30,000 prostitutes worked the island of Manhattan. An informal estimate: “One of every six adult men in New York City paid for sex.”

Overseeing, or overlooking, all this was Tammany Hall and a corrupt police department defined by brutality, bribes, collusion and shakedowns. To change it, new mayor William L. Strong appointed Roosevelt, who’s generously described by Zacks as “energetic, stubborn, opinionated.”

Roosevelt pursued vice with the tenacity and single-mindedness that would mark his entire public life. He and friend Jacob Riis, the muckraker and social reformer, would go on post-midnight missions to see whether cops were doing their duty. They found out in a hurry.

He also got saloons closed on Sunday, enforcing the law at 12:01 a.m., “trying to shut down Saturday night for the city at the stroke of midnight.” But those with means still drank in their residences and clubs. Roosevelt would acknowledge privately that the law was “altogether too strict.”

An irritated citizenry never heard that, and found ways to obtain alcohol, a preview of creativity during Prohibition. Challenged, Roosevelt extended crackdowns beyond saloons to gambling and prostitution. “Ultimately, his fix for vice was simply virtue,” according to Zacks.

But New York wasn’t for puritans. Roosevelt’s popularity tanked. Republicans rumbled. Tammany would win elections. Roosevelt went to Washington. Yes, he’d helped spur the righteous. But, Zacks adds, “As in ancient Rome, the vitality of New York City sometimes seems to come more from the crooks than the do-gooders.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.