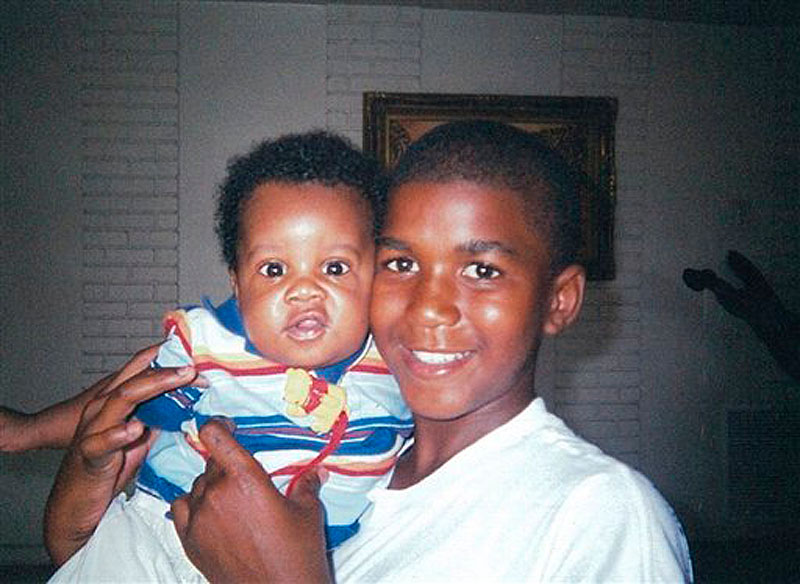

MIAMI — George Zimmerman persuaded the police not to charge him for killing unarmed teenager Trayvon Martin, but the prosecutor has accused him of murder. Soon, armed with unparalleled legal advantages, Zimmerman will get to ask a judge to find the killing was justified, and if that doesn’t work, he’ll get to make the same case to a jury.

The wave of National Rifle Association-backed legislation that began seven years ago in Florida and continues to sweep the country has done more than establish citizens’ right to “stand your ground,” as supporters call the laws. It’s added second, third and even fourth chances for people who have used lethal force to avoid prosecution and conviction using the same argument, extra opportunities to keep their freedom that defendants accused of other crimes don’t get.

Martin’s shooting has unleashed a nationwide debate on the validity of these laws, which exist in some form in most of the country and which prosecutors and police have generally opposed as confusing, prone to abuse by criminals, and difficult to apply evenly. Others are concerned that the laws foster a vigilante, even trigger-happy mentality that might cause too many unnecessary deaths.

An Associated Press review of federal homicide data doesn’t seem to bear that out. Nationwide, the total number of justified homicides by citizens rose from 176 in 2000 to 325 in 2010. Totals for all homicides also rose slightly over the same period, but when adjusted for population growth, the rates actually dipped.

At least two-dozen states since 2005 have adopted laws similar to Florida’s, which broadly eliminated a person’s duty to retreat under threat of death or serious injury, as long as the person isn’t committing a crime and is in a place where he or she has a right to be. Other states have had similar statutes on the books for decades, and still others grant citizens equivalent protections through established court rulings.

While the states that have passed “stand your ground” laws continue to model them loosely after Florida’s — Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and New Hampshire put expanded laws on the books last year — Florida is unique.

One area that sets Florida apart is the next step Zimmerman faces: With the police and prosecutor having weighed in, a judge will decide whether to dismiss the second-degree murder charge based on “stand your ground.” If Zimmerman wins that stage, prosecutors can appeal.

But in another aspect peculiar to Florida, if the appeals court sides with Zimmerman, not only will he be forever immune from facing criminal charges for shooting the 17-year-old Martin — even if new evidence or witnesses surface — he could not even be sued for civil damages by Martin’s family for wrongfully causing his death.

“You get even more protection than any acquitted murderer,” said Tamara Lawson, a former prosecutor who now teaches at St. Thomas School of Law in Miami. “This law seems to give more protection than any other alleged criminal could dream about.”

If Zimmerman can’t convince the judge of his innocence, he still can use “stand your ground” to convince jurors.

Zimmerman, 28, is facing up to life in prison if convicted of second-degree murder for shooting Martin on Feb. 26. A neighborhood watch volunteer in the central Florida town of Sanford, he said he fired his 9 mm handgun after Martin attacked and beat him. Martin’s family and supporters claim Zimmerman was the aggressor, targeting Martin for suspicion mainly because he was black. Zimmerman’s father is white and his mother Hispanic.

His attorney, Mark O’Mara, said Zimmerman will plead not guilty and seek dismissal of the charge using “stand your ground.” Many legal experts think he’s got a good case, particularly if there are medical records backing up his claim that Martin broke his nose and slammed his head on a sidewalk. Other experts say, however, that the law will not protect Zimmerman if he was the aggressor.

The special prosecutor in the case, Angela Corey, said she fully expects a fierce battle over the self-defense claim.

“If ‘stand your ground’ becomes an issue, we fight it if we believe it’s the right thing to do,” she said.

The U.S. Supreme Court has never weighed in on the constitutionality of such laws, and none has been struck down by a lower court. Defendants have sought dismissal of charges based on “stand your ground” claims in all kinds of cases, and defense lawyers say its use is growing.

Last month, a Miami-Dade County judge ruled that Greyston Garcia was immune under the law even though he chased down a suspected car stereo thief and stabbed him to death, then went home and went to sleep. The judge ruled Garcia used justifiable force because the thief swung a bag of radios at him that could “lead to serious bodily injury or death.” Prosecutors are appealing.

In Tampa last year, investigators decided not to file charges against 62-year-old Alcisviados Polanco, who used an ice pick to fatally stab 20-year-old Wathson Adelson following a road rage confrontation. Authorities said there was no evidence to disprove Polanco’s claim of self-defense.

Two years ago in Miami, a pair of Florida Power & Light workers were accosted by a mobile home resident armed with a rifle. The resident, Ernesto Che Vino, struck one utility worker on the head and fired shots in the air as they fled to their vehicle. A judge ruled that Vino’s actions were justified because he was in fear for his life.

Numbers compiled by the FBI suggest many states saw modest or even sharp increases in the number of homicides by private citizens that were classified as justifiable after enacting a “stand your ground” law or amending existing self-defense laws.

The trends are most pronounced in larger states like Texas, which expanded its law in 2007. Between 2008 and 2010, Texas averaged 47.7 justifiable homicides per year for a total of 143 — up from an annual average of 33 and a total of 99 justifiable homicides between 2005 and 2007, according to the FBI data.

Still, justifiable homicides by citizens remained a tiny fraction of all homicides in Texas before and after the law was enacted — 2.2 percent between 2005 and 2007 and 3.3 percent between 2008 and 2010.

Arizona and Georgia also reported increases in justifiable homicides after enacting their respective laws in 2006. Arizona averaged 18 justifiable homicides per year between 2007 and 2010 for a total of 72 — up from a total of 38 and an annual average of 9.5 between 2003 and 2006. Georgia averaged 7.5 justifiable homicides per year between 1995 and 2006 and averaged 14.8 annually between 2007 and 2010.

The FBI data for some states didn’t significantly change after the new laws took effect. Louisiana, which enacted its law in 2006, averaged 12.3 justifiable homicides per year between 2007 and 2010. Between 2003 and 2006, it averaged 11.5.

The FBI numbers are based on voluntary reporting by law enforcement agencies and aren’t comprehensive, which means they can’t serve as ironclad evidence that expanding a person’s right to protect life, limb and property leads to increases — or decreases — in the numbers of homicides deemed justifiable.

Small sample sizes in many states make it difficult to determine if the new or amended laws have had a practical effect. The way law enforcement agencies report the data also could explain why some states report increased numbers of justifiable homicides. For instance, yearly comparisons could be skewed if larger agencies in a state changed their reporting systems or only recently started reporting the data to the FBI.

Florida’s justifiable homicides nearly tripled after the state enacted its law in 2005, according to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, from an annual average of 13.2 between 2001 and 2005 to an average of 36 between 2006 and 2010.

With prosecutors and police raising concerns about misuse and unintended consequences, the Martin case has spurred Republican Gov. Rick Scott to create a task force to examine whether “stand your ground” needs changes. Both the law’s original legislative sponsor in Florida and former Gov. Jeb Bush, who signed it into law, have said the law wasn’t intended to apply in cases such as the Martin shooting.

The Florida shooting has sparked a national campaign against such laws as well. New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, along with several civil rights organizations, is leading an effort to repeal or reform laws similar to Florida’s, though it’s too soon to say if that movement will gain traction.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.