Today marks the centennial anniversary of the sinking of the RMS Titanic, at the time the largest movable object built by man. Her life was brief: Striking an iceberg in the North Atlantic on her maiden voyage, the pride of the White Star line went down in two hours and forty minutes, taking 1,523 souls down with her.

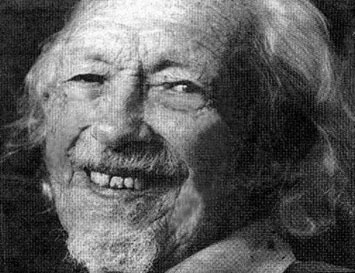

On the 100th anniversary of the Titanic’s demise, it is fitting to recall survivor Marshall Drew’s opening words in an interview with me more than a quarter of a century ago in his Westerly, R.I., home.

“This Titanic thing — it’s always been with me.”

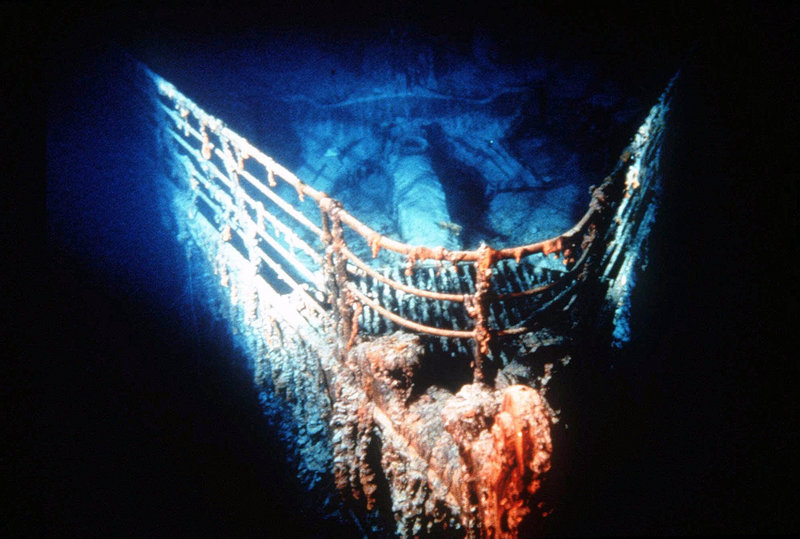

Marshall’s indelible memories were tapped after Capt. Robert Ballard from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, along with a French exploration team, discovered the elusive liner in 1985. Virtually the last survivor to have memory of the doomed ship — remaining survivors were infants, toddlers or small children at the time — Drew was able to identify many features of the underwater footage, including the area of the Grand Staircase.

Our March 1986 interview proved to be his last. The blithe, elfin man of 82, with a shock of white hair and glistening eyes, passed away six weeks later.

With his passing, a thread of history also snapped — a delicate link to the Edwardian world that sank in the darkest hours of April 15, 1912. Eight-year-old Marshall Drew was one of the 705 fortunate passengers to escape one of Neptune’s cruelest harvests.

He would never forget those haunting hours.

BAD OMEN? SOME THOUGHT SO

Young Drew’s voyage from New York to Southampton, England, on the Olympic (the sister ship of Titanic) was, in his words, “boring.” His return trip on the RMS Titanic’s maiden voyage would be anything but.

Waiting for the giant ship to sail, Drew caught the excitement of a near miss in Southampton Harbor. Titanic’s suction caused a smaller vessel, the New York, to break her lines, and the ships almost collided. But he thought nothing of it.

Others apparently did, considering it an omen. Indeed, there were 55 cancellations for Titanic’s sail, with reasons ranging from omens to illness.

Traveling with his aunt and uncle, the energetic British-American lad was visiting his Grandmother Drew in Cornwall, England. Granny was hardly overjoyed with Marshall’s presence, however, admonishing his aunt “to get that kid out of the house.”

Carted off to a farm to stay with his cousins, the boy enjoyed his stay immensely.

But all good times must end, and Marshall, Aunt Lulu and Uncle Jim Drew booked second-class passage on the much heralded new star of the White Star Line.

Because the Drews were in second class, Uncle Jim and Marshall were allowed to tour the Titanic. They poked their heads in the gymnasium where a mechanical camel provided a novel form of exercise, as did a swimming pool, the first of its kind on a luxury liner.

Ducking into the exotic Turkish bath, Marshall was quickly redirected to the barbershop, which sold souvenirs. Uncle Jim bought Marshall a ribbon which read “RMS Titanic”: It was the only thing the boy saved when rushed to the lifeboats that fatal night.

Uncle and nephew gazed upon the Grand Staircase, where the “who’s who” list of 1912 — Astors, Guggenheims, Strauses and even the Gibson girl herself, silent film star Dorothy Gibson — would make their bejeweled entrances to dinner under the ornate statue, “Honor and Glory Crowning Time.”

Four city blocks long and 11 stories high, the Titanic represented one of humankind’s finest accomplishments. But the boy’s reaction to this floating horn of plenty was short and not so sweet: “I was not impressed with the expense.”

As the Edwardian lad settled in for a lonely, boring trip to the States, he sized up his situation: No cousins or friends to play with, no running, jumping or just plain having fun. Not that there weren’t other children on board; but in 1912, social dictum required them to act like little men and women.

That same social etiquette translated into family reactions to the disaster. Once in New York, Aunt Lulu forbid her nephew from ever mentioning Titanic again.

“Ever” meant “one day” to Marshall, a mistake he wouldn’t repeat until Walter Lord’s book, “A Night to Remember,” was released in 1955.

ICEBERG WARNINGS GO UNHEEDED

It was approaching midnight on the eve of April 14, and the Titanic was racing through the iceberg-packed North Atlantic at 22.5 knots. Six ice warnings had been issued that Sunday, issued but not heeded. A lifeboat drill had also been scheduled, but Capt. Edward J. Smith, a seasoned seaman and preferred captain of yesteryear’s “1 percent,” was talked out of it. Seems that some first-class gents wanted an uninterrupted squash game.

At 11:40 p.m., the crow’s nest rang the bell cord three times with the alert “iceberg ahead.” As the looming black shield of ice grew nearer, lookout Fred Fleet again rang a warning.

It was too late. The bridge overcorrected to a hard a starboard, and the Titanic’s fate was sealed. In first class, an unexpected stash of ice appeared for drinks; in second class, motion ceased; and in third class, water rushed in immediately.

A steward rapped at the Drews’ cabin door and told them to dress and put on their life-belts. As Marshall walked up to the deck with his aunt and uncle, he looked over his shoulder and saw armed officers guarding a locked gate.

He also heard pistol shots.

“Even at 8, I knew what was happening,” he recalled, referring to the steerage passengers locked below deck.

Drew was struck by the tearful farewells and how calm everybody was as he and his aunt were loaded into lifeboat number 11. It was the only lifeboat to be filled to capacity: 70.

Drew was scared now — not so much of the ship sinking, but of the lifeboat itself. Nothing worked: The pulleys stuck, and the boat jerked right, then left, almost dumping its occupants into the 28-degree water.

As lifeboat number 11 finally rowed out to safety, Drew remembers “not being able to tell the difference between the sky and the sea.” The moonless night was pitch black, and the boy watched row after row of porthole lights disappear into the abyss.

What the boy couldn’t see, he heard. He vividly recalled the sound and fury of machinery tearing loose, and steam, sparks and fire spewing from its giant funnels.

He also never forgot the screams of passengers when the liner’s bow plunged and her stern rose perpendicular before breaking in two.

“I wore a chinchilla coat in the lifeboat,” said Drew. “That tells you the circumstances.”

Being a child, Drew dealt with the horror by stretching out in the bottom of the lifeboat and going to sleep.

NEW DAY DAWNED, AND TITANIC WAS GONE

Drew’s next recollection was waking up and seeing the rescue ship, Carpathia, alongside the bobbing white lifeboat. It was early morning, and ice was everywhere. Nowhere was the Titanic, however — only floating, grisly testaments to its existence.

Marshall counted 25 icebergs while he waited to be lifted onto the Carpathia. Other children screamed at the prospect of being hauled on board in canvas sacks, but he considered this part “a pretty good ride.”

“When the sailor dumped me out, I took off to get breakfast,” he said. “I figured my aunt could take care of herself.”

Drew and his aunt were put up in Blake’s Hotel in New York City, and he remembers his aunt and other family members going shopping and leaving him alone.

“You could do that then,” he observed casually.

Left to his own devices, the 8-year-old found some stationery and a penknife in a desk drawer, and set about pen-pricking an outline of Titanic as she sank. Held up to the light, it resembled a tintype.

The next day, a reporter from the New York World discovered the artwork and interviewed the young survivor before his aunt could stop him. The article ran with the heading, “Young Drew’s Account of the Sinking of the Titanic.”

An artist and teacher was born.

Drew would go on to graduate from the Pratt Institute and teach fine arts in New York schools for more than 35 years. Art, he believed, was a universal language, and a way he could give back.

The 8-year-old boy who realized the chinchilla coat in the lifeboat defined his survival also believed that art knew no social standing, no rigid social class.

“Teaching I did on purpose. The Titanic was purely accidental,” concluded the survivor. “I’ve had a good life, an active life. Guess you could say I’m lucky.”

Karen M. Lemke is associate professor of education at Saint Joseph’s College of Maine in Standish, and a member of the Titanic Historical Society Inc.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.