A long time ago, Pat Nick invited me to come to the Vinalhaven Press and make a print. It was an aberration on her part and an epiphany for me. Deprived of functional skill in the arts, I fumbled my way through two etchings. One was a disgrace; the other so fills me with wonder that it hangs in my bedroom and I look at it every day.

The point of the invitation was to give me a sense of the technology of printmaking. As venerable as prints are, the vocabularies of their manufacture so obscure the processes behind them that the usual observer is helpless. If he can distinguish a classical wood engraving from an equally age-sanctioned etching, he is ahead of the pack.

It adds immeasurably to the pleasure inherent in a print if you can understand the method used to create it. The print’s image once floated somewhere between the psyche of the artist and the paper on which it appears. The method of depicting or amending the image, whether through cutting into wood, drawing on a stone or penetrating the surface of a sheet of metal, makes all the difference in what we see.

The choice of exposition by the artist is the nub of the matter. Cutting a woodcut is physical and exhausting and results in a harsh fluency; lithographs are at ease but aloof; and etching offers the mind and hand of the artist the universe. In each of them, an artist using a poverty of means can play out his destiny.

These thoughts about classic disciplines ignore the technologic expeditions of contemporary printmaking. I find their brilliance bewildering.

In both Lewiston and Portland, this is a felicitous time to look at some splendid prints.

The Lewiston event is at Captive Elements, a new gallery in that city. It presents work by Kyle Bryant, Dan Coulombe and Edward Trujillo.

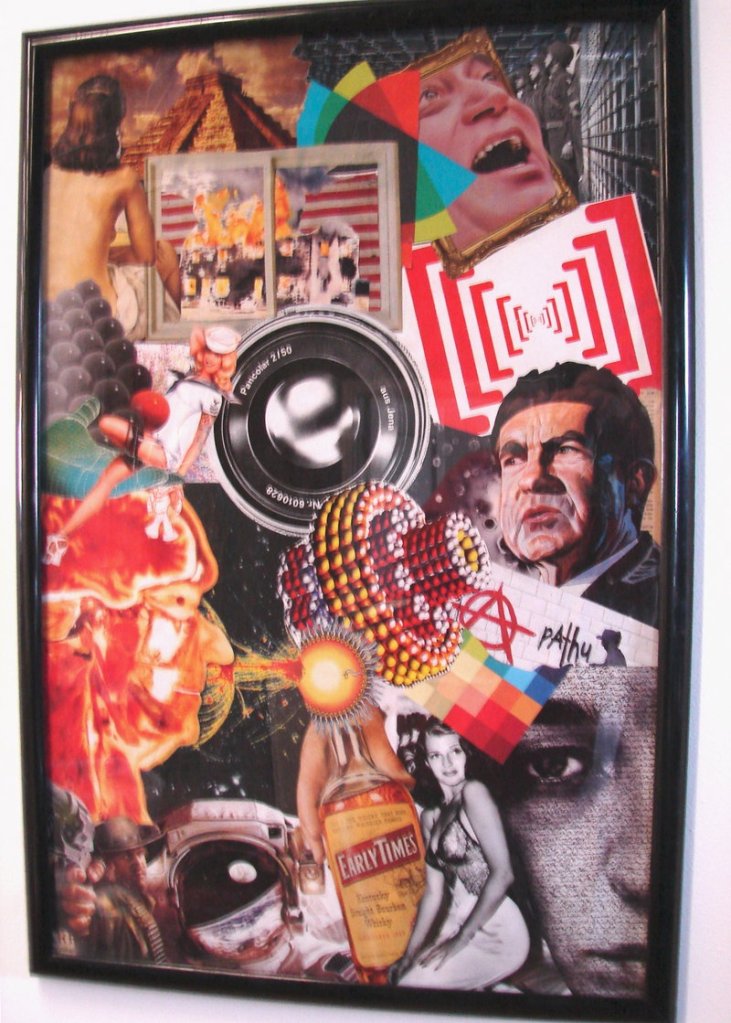

Of the three, only Bryant is a printmaker, but I mention Coulombe’s collages for their graphic impact and avoidance of artiness. The images are excerpted from popular sources — old magazine covers, ads, etc. — and presented in your face.

The work relies on the removal of forms from the original sources and reforming them as abstractions while preserving the abstractee’s narrative content. In other words, you can still read the images on the skillfully torn sheets.

I point this out because in one collage, “Early Times,” a circa-WWII image of actress Rita Hayworth appears. With the possible exception of a certain view of Betty Grable, that picture of Hayworth was posted on more footlockers than any other wherever American boys marched. It reminded them that they were fighting for more than Mom, apple pie and the Brooklyn Dodgers. It’s a pleasure to run into an old friend.

Bryant’s woodcuts are spectacular achievements. They are large and formally complex, and have exceptional fluidity for a medium that tends to hit the paper and achieve an instantaneous knockout. They are so animated that I needed assurance from the staff that I was looking at a woodcut printed directly from the block rather than at a drawing.

I note in particular the huge “A Long Break From Love” and “Can’t Stop Won’t Stop.” Each is an impressive technical achievement and, in lineal terms, explosive.

THE PORTLAND VENUE is at A Fine Thing, otherwise known as Edward T. Pollack Fine Arts, where prints by Don Gorvett and Sean Hurley are on exhibit. Hurley is an etcher, and Gorvett a maker of a rare and complex form of woodcuts.

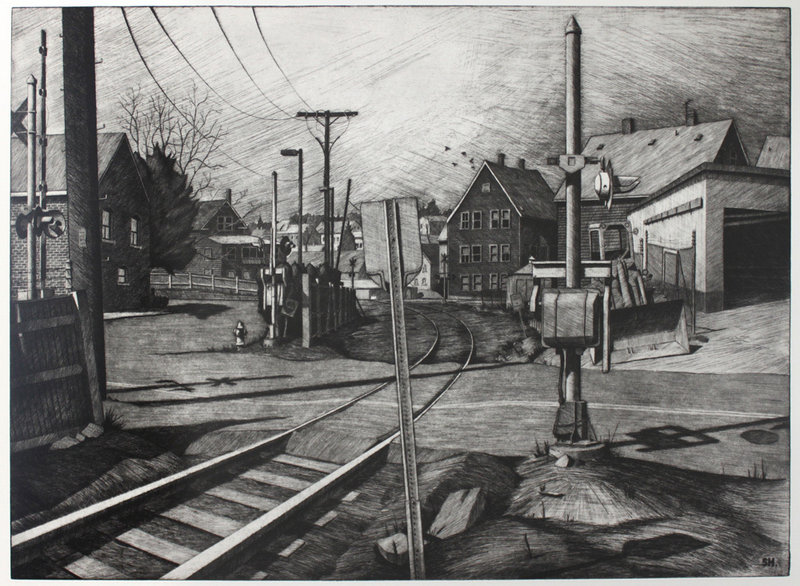

Speaking as an architectural fanatic, a would-be photographer and as a person responsive to geometric abstraction, Hurley’s bounteous etchings fill me with great joy. They begin where photography would end and make a photographer yearn to become a printmaker, yearn to make a fixed world conform to the improvement imbedded in his vision.

To put it otherwise, in their embrace of derelict buildings, the rough deposits of industry and the restlessness of the modern landscape, the etchings move beyond the limits of a photographic eye into the agitated eye of a graphic artist. The embrace of that eye may be grim, in which case we find linearity and unyielding detritus. It may also be generous, in which case the world softens, turns introspective and offers us easy metaphors. The abundance of the images in Hurley’s etchings is thrilling.

I also point out the consistent level of Hurley’s prints. Each is admirable for its narrative, and all are admirable for the rich beauty of their printing.

The Gorvett prints are ravishing in their size, complexity and aura of accomplishment. They have the stature of works of art defined in intention and beautifully achieved. The method of that achievement is a difficult process called multi-color reduction.

Using a single wooden block, Gorvett is able to bring forth a full bravura colored edition of prints. His technique involves the carving and recarving, in succession, of a surface in the sole block that must serve for each color that is to ensue. Each prior surface in the block is destroyed in the production sequence. In the process of reduction woodblock cutting, time must be an endless vista.

Gorvett’s images are bold, sympathetic views of Gloucester and bits of Maine and New Hampshire. They are about as close to painting as a print gets, and for the geometry inherent in his subjects, they are ideal.

His physical efforts with the block descend layer after layer — as lingering ghosts — on to the final impression. You can feel them in each level. Their archaeologic presence contributes voluptuousness to the result.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 47 years. He can be contacted at: pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.