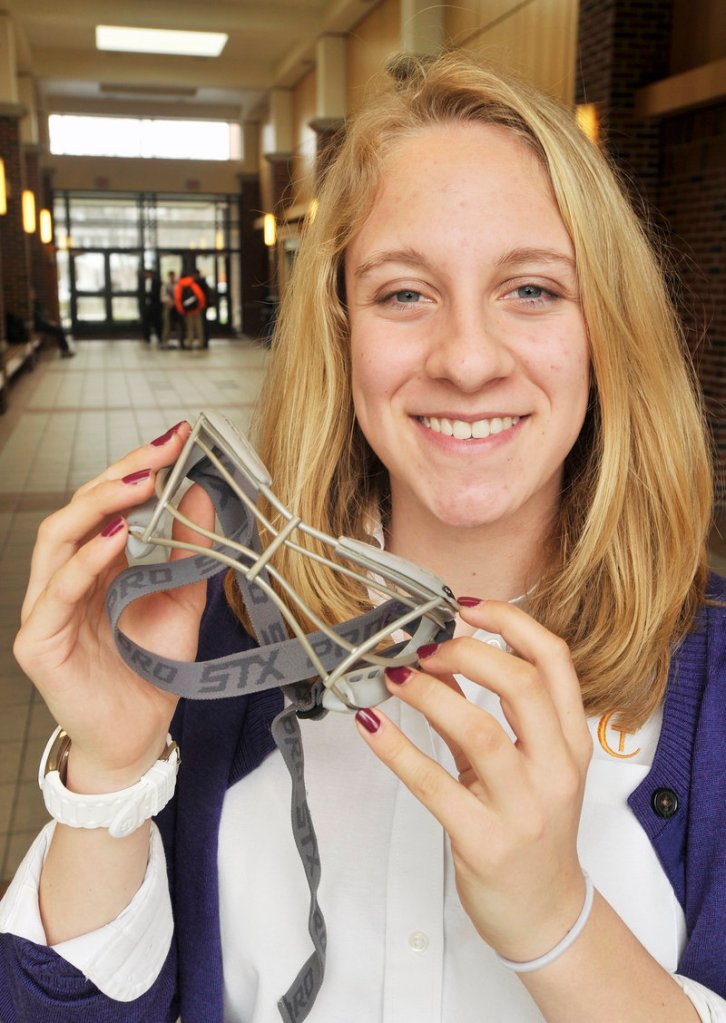

Alex Logan never thought much about the protective goggles she wears while playing field hockey. At least until they saved her face.

In a game played last September, Logan, a sophomore at Cheverus High in Portland, took a hard drive to the face that struck her goggles.

Play immediately stopped but Logan was fine, save for a scratch on her nose, and returned a couple of minutes later.

“Honestly, I don’t know what would have happened if I wasn’t wearing goggles,” said Logan. “It could have been very serious. … I could have lost an eye.”

Logan’s experience is at the heart of a debate — whether the goggles are more harmful than they are protective — that has divided the field hockey community.

Last fall, the National Federation of State High School Associations mandated the use of protective eyewear for field hockey players on its member teams — the Maine Principals’ Association had required it for Maine high schoolers four years earlier. The NCAA, which oversees college sports, is now researching whether to mandate goggles for its players.

Proponents say the goggles protect players against catastrophic eye injuries.

“There is no real downside to (goggles), other than being a little uncomfortable,” said Dr. William Heinz, an orthopedist at Orthopaedic Associates in Portland who serves on the national federation’s medical advisory board. “It’s not a huge cost to buy them. But there is an enormous benefit to having them when you think about the cost of losing an eye.”

But many coaches say safety concerns are misplaced and that goggles cause as many injuries, such as facial lacerations and concussions, as they prevent because they restrict a player’s vision.

In New Jersey and Pennsylvania, coaches last fall publicly decried the high school mandate, citing numerous instances of their players running into each other and ending up with either cuts or concussions because their vision was restricted.

Even in Maine, where wearing goggles has been required since 2007, some coaches don’t care for them.

Paula Doughty, who has coached Skowhegan to 10 Class A state championships in the past 11 years, said her players — many of whom play on U.S. Field Hockey national teams — wear them only during the high school season.

“They’re dangerous,” she said. “They restrict the vision of the kids. I’ve had more injuries with them since we’ve had to wear them. Kids run into each other all the time. They just lose the ball where they never used to lose the ball.”

Kaylee Heath, who played at Gardiner Area High School and just finished her freshman year at Saint Joseph’s College in Standish, said she suffered a gash on her forehead from a collision while wearing goggles in high school.

“I was kind of looking forward to playing in college because I wouldn’t have to wear the goggles,” she said. “I’m sure there are benefits — say, a girl swings her stick high and it hits you in the face, or the ball comes flying up. But for me, the whole thing is seeing the ball. And it’s very difficult with the goggles.”

SUPPORTERS CITE EYES’ VULNERABILITY

According to the national high school federation’s latest statistics, there are 61,996 girls playing high school field hockey in 19 states.

Until last fall, players had been allowed, but not required, to use eyewear meeting safety standards set by the American Society for Testing and Materials. On April 13, 2011, the federation approved a requirement that all field hockey players wear protective goggles starting with the 2011 fall season.

The federation’s Field Hockey Committee had voted 9-0 against requiring goggles but was overruled by its Executive Committee, which sided with recommendations made by its Sports Medicine Advisory Committee.

That group concluded that goggles would not hinder players or cause more injuries, citing data drawn from a national injury study by Dawn Comstock of the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Ohio State University.

“We had long discussions about what might happen,” said Heinz, the Portland orthopedist and Sports Medicine Advisory Committee member.

“We worried about unintended consequences. We looked at several sports where they went from non-goggles to goggles, such as lacrosse. There really weren’t any increase of injuries from non-goggles to goggles.

“The feeling of the advisory board is that an eye injury is such a catastrophic injury, put a goggle on it so we can prevent (players) from losing an eye.”

Comstock, who has been providing injury data to the national federation for the past seven years, agrees. She said her research, which is based on information submitted from athletic trainers across the nation, indicated that eye protection was something the national federation should consider.

While eye injuries are rare in field hockey, Comstock’s annual injury study — the High School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study (injuryresearch.net/highschoolrio.aspx) — indicated that there were a higher percentage of injuries to the head or face in field hockey than to any other body part over each of the past three seasons: 25.9 percent in the 2010-11 school year, 24 percent in 2009-10, and 24.9 percent in 2008-2009.

“A catastrophic eye injury is a permanent injury,” she said. “An ankle injury, you can come back from. A knee blowout might cause an athlete to retire from the sport, but it probably would not affect the rest of his or her life. You can still walk. An eye injury? There’s no way to replace it.”

And that’s why the goggles rule will stay in place, despite calls to revoke it after just one year, according to Bruce Howard, a spokesman for the national federation.

CRITICS POINT TO INJURIES FROM COLLISIONS

Maine has been at the forefront of the issue. Many players wore goggles even before they were required.

In 1999, a Marshwood High freshman field hockey player lost an eye after getting hit in the face by a teammate with a hockey stick during a drill before a game. Her parents sued the school, which was not found liable for the accident but agreed to pay medical expenses.

That fall, Marshwood had its players wear wire-framed goggles designed for lacrosse players, which are similar to the type worn for field hockey. Maine was among several states to require the protective eyewear for the 2007 season.

“I have mixed emotions about them,” said Barb Marois, York High coach and former U.S. Olympic field hockey player (who never wore goggles when she played). “I wasn’t sure of the necessity of them. And we went through some growing pains at first. We had a lot of girls bonking heads. I guess I should have put them on myself to see what the girls were going through.”

Moe McNalley, the veteran coach at Gardiner, said that she still sees those collisions five years after the goggles were first mandated.

“I don’t see any serious injuries,” she said. “But injuries that we would not have had otherwise if the kids had been able to keep their heads up. The kids run into each other. Those are the types of issues we still battle with.”

Those types of injuries, as well as concussions, were cited by field hockey coaches in states that did not previously require goggles.

Coaches in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, two marquee field hockey states, said their players were suffering more facial cuts and concussions caused by head-on collisions between players whose vision was impaired by goggles.

Cris Mahoney, a New Jersey field hockey official, established the website goggleinjury.com to collect reports of field hockey injuries caused by goggles from parents, coaches, players and trainers.

Last year, 75 injuries were reported in 12 states. Of those, 47 were to the face, including cuts that required stitches, bruises and concussions. While the reports are anecdotal, Mahoney said the results are conclusive.

“In the face of the (National Federation of State High School Associations) saying goggles are not dangerous, this clearly shows they are dangerous,” he said.

COLLEGE COACHES LEERY OF REQUIREMENT

Field hockey is an international sport, played competitively at many different age levels. Yet only U.S. high school players are required to wear protective eyewear. It is not mandated at the collegiate level, the national level (for U.S. Field Hockey events) or the international level.

“I was at the (national) festival this year, and I saw one team wearing goggles,” said Pam Stuper, field hockey coach at Yale University and an executive board member for the International Hockey Federation (the worldwide governing body for field hockey). “We had 26 fields being used, and only one team wore goggles. And these were kids who just stepped off the (high school) playing field a couple of weeks earlier.”

Skowhegan’s Sarah Finnemore, a junior midfielder who has committed to play at Harvard, is on this year’s U.S. Field Hockey junior national indoor team. She doesn’t wear goggles in U.S. Field Hockey events and notices a big difference when she plays high school games.

“When you start the preseason, it takes a while to get used to it,” said Finnemore. “You have to learn to adapt to vision you lose with the goggles. You have to keep your head down more to focus on the ball and what you want to do is look up so you can scan the field for the next play.”

For those reasons, college coaches aren’t eager to see them come to their sport.

“I think it’s a good thing for the high school level because I don’t think those student athletes are at the (talent) level we play at,” said Rupert Lewis, the head coach at Saint Joseph’s College. “I think that once you get to college, because you’re competing at a higher level, you don’t find the incidence of injuries at the same level as you do in high school.”

Yale’s Stuper, who was a teammate of York’s Marois at the international level, said the international community is watching events closely.

Three times a year she meets with other members of the International Hockey Federation and, she said, “We are the laughingstock of the world when it comes to this. They look at me, as a representative of the United States, and say, ‘What are you guys doing?’ I have no idea.”

Stuper said that field hockey will be affected adversely if the NCAA mandates the use of protective goggles.

“We have a lot of internationals come to play because our college system is one of the premier systems in the world,” she said. “Those international players will not come if they have to wear goggles. They haven’t had to wear them their entire life. … It will hurt the level of field hockey.”

NCAA WEIGHING GOGGLE MANDATE

It is not surprising that coaches who never wore goggles are opposed to them. Opposition to protective gear has always been strong, said Comstock, the Ohio State researcher.

“Whenever new pieces of protective equipment have been introduced to a sport, there’s always a group of people saying, ‘You’re going to ruin the culture of the sport,’ ” she said.

“The introduction of the football helmet … the face mask to the helmets … the introduction of ice hockey helmets … Every sport resists change when there’s an introduction of protective equipment,” she said. “It’s nothing new. It’s always interesting that people say, ‘We can’t do this.’ If you look at every sport, it has evolved over time, including field hockey.”

College coaches point out that recent rules changes have made the game safer, eliminating the need for the goggles.

“Defenders are not stationary anymore,” said Josette Babineau, head field hockey coach at the University of Maine. “They are moving when the ball is hit. They’re not reacting to people hitting the ball at them.”

But that might not be enough for the NCAA, which is now considering whether it will mandate the use of goggles for its field hockey players. It won’t happen next year, according to NCAA spokesman Cameron Schuh. “But it is being heavily discussed.”

“There has been a big push from the NCAA as far as safety goes,” said Nicky Pearson, coach at Bowdoin College, which has won NCAA Division III national championships in three of the past five years.

“And I think it’s very much a point of debate at the moment. I don’t think there’s a coach out there that wants to see any injuries to any of their athletes, especially to the face or head,” she said.

But coaches want the NCAA to thoroughly research the issue before mandating anything.

For those who have experienced a hard shot off the goggles, that means only one thing.

“There’s no way,” said Faith Logan, the mother of Alex Logan, “that goggles cause more injuries than they prevent. That’s my opinion.”

“When she got hit, those were the worst 10 seconds of my life.”

Staff Writer Mike Lowe can be contacted at 791-6422 or at:

mlowe@pressherald.com

Twitter: MikeLowePPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.