Roscoe Filburn was a farmer. He sold milk and eggs to 75 regular customers every day. But it was his wheat crop that got him in trouble with the law.

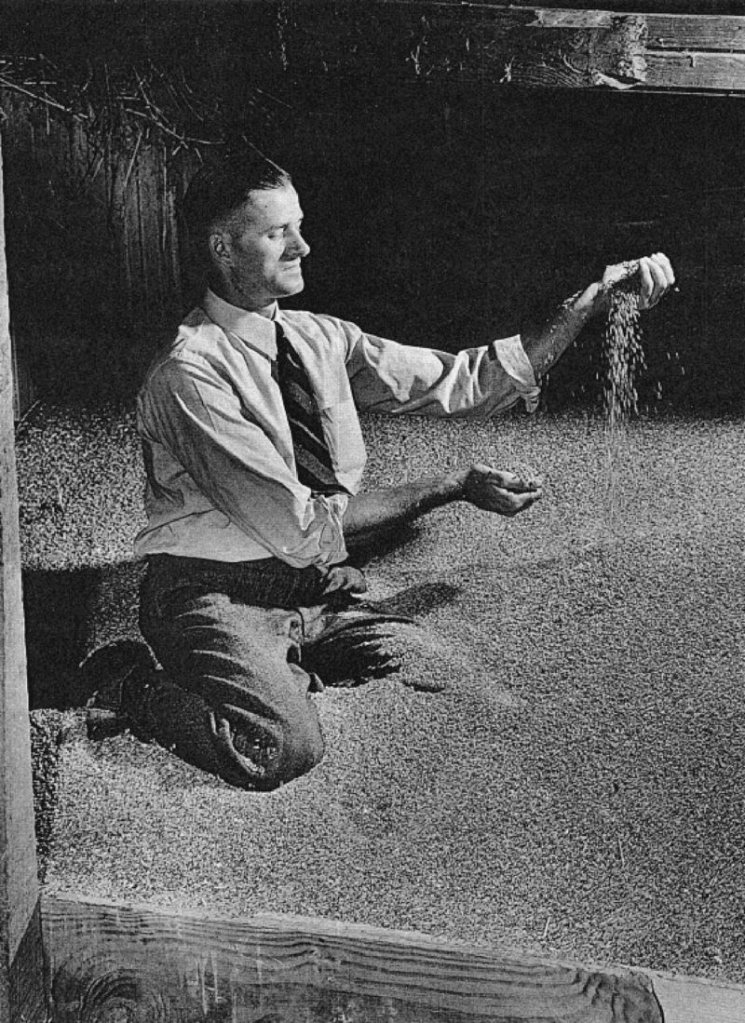

Filburn’s farm in Ohio sported some 95 acres of good fertile land. In 1940, he planted 23 acres of wheat and harvested 462 bushels the following July.

He had no interest in putting his crop on a train and sending it to California or Maine. He grew grain only to feed his own livestock. Besides, because of a surplus, farmers could not get a good price for wheat in 1941. A few years earlier Congress had passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act, imposing price controls and strict quotas on wheat farmers.

Roscoe Filburn’s crop was a few bushels over the line. So the federal government came down on him. His case went all the way to the United States Supreme Court, and in a unanimous 1942 ruling the court concluded that the federal act passed constitutional muster under the Commerce Clause, stating:

“That the production of wheat for consumption on the farm may be trivial in the particular case is not enough to remove the grower from the scope of federal regulation where his contribution, taken with that of many others similarly situated, is far from trivial.”

It is Roscoe Filburn’s case that the Supreme Court will grapple with as it decides whether the Affordable Care Act — including the mandate that Republican lawmakers for years proposed as a question of individual responsibility — is constitutional.

If Congress can prevent each of us from growing a bushel of wheat (or, in a later case, a marijuana plant), can it also require health insurance coverage for 45 million uninsured people — 15 percent of the population, helping hospitals survive and preventing personal bankruptcies? Can it regulate a $43 billion-plus industry that makes up more than 17 percent of our gross domestic product?

Opponents say, “Maybe Congress can prevent me from doing something that affects the economy, but how can it make me do something I don’t want to do!”

Some say, “How can the government make me buy insurance?” Others ask, “Why do I have to pay more for insurance because people who can afford it choose not to buy it?”

The question is not simple, and the consequences of the court’s ruling may be far-reaching. Let’s look at history:

• In 1937, George Davis did not want to pay the payroll tax funding Social Security. He argued that providing for the welfare of the elderly was a power reserved to the states. The Supreme Court disagreed and the Social Security mandate was upheld.

• A few years later, the Darby Lumber Company did not want to pay the new federal minimum wage or restrict its employees’ hours; in 1941 the Supreme Court ruled that Congress had a right to enforce the Fair Labor Standards Act against Darby Lumber.

• In 1964, the folks at Ollie’s Barbecue in Birmingham, Ala., and the Heart of Atlanta Motel in Georgia refused to serve people of color; the Supreme Court said Congress could make Ollie’s serve barbecue and the Heart of Atlanta rent rooms to people regardless of race, creed, religion or national origin.

What about paying premiums for Medicare? Unemployment compensation insurance? Requiring people convicted in state courts to register on a federal sex offender database? What about federal health and safety mandates?

Some judges have said that the question is not about acting or not acting; rather, it is the many individual decisions not to buy insurance that, in the aggregate, shift the costs of health care all across the country, with a pronounced effect on interstate commerce.

As Charles Fried, President Reagan’s solicitor general, put it, “My copy of the Constitution doesn’t have an individual right not to be insured.”

“I’m prepared to say it’s complete nonsense,” he added, referring to the challenges to the reform law. “If you don’t sign up for insurance, then you’re going to be some kind of drag on the system,” he said, arguing that the federal government has a right to impose a tax on behavior that costs society as a whole.

When the court rules this summer, the ghost of Roscoe Filburn may be sitting with the justices. But there is a lot more than health care at stake. It is entirely possible that many of the individual rights and privileges we take for granted in this country will also be in jeopardy.

Janet Mills is the former attorney general for the state of Maine.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.