Now on view at Art House in Portland, Alina Gallo’s “Rising” is one of those shows that immediately forces a sense of caution — even danger.

The style takes its technique and aesthetic from Persian miniatures, and the subjects are steeped in Middle Eastern controversy: The enlightenment of Mohammad, a massacre in Kandahar, the destruction of Homs, the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, and so on.

Americans have developed a fearful reflex regarding the appropriation of Islamic imagery in the wake of the well-publicized fatwa issued against Salmon Rushdie in 1989 and the 2005 Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy that led to the bombing of the Danish embassy in Pakistan and violence at Danish embassies throughout the Middle East.

What we Americans know in general about Islamic art is just enough to make us nervous. For example, many people who think they know a great deal about art believe (wrongly) that figurative art is completely verboten for Muslims.

Gallo’s style only complicates such questions. Her newest work features a highly refined egg tempera technique associated with Persian miniatures. Muslim miniatures, however, represent a syncretism of Arab decorative styles with Christian and Byzantine manuscript illumination — something like an early post-modernism.

“Rising” comprises 14 small works in a very small space, but their miniaturist scale, technique and sense of detail benefit from the intimacy of the space. Between the visual density of the paintings and the anxiously complex conceptualism of their content, there is a lot to see. In a very real sense, “Rising” is a big show. It’s also tantalizingly unresolved — it wears its tensions well.

Gallo’s works self-divide into three modes: Three works from 2010 have an un-ironic take on classical Islamist narrative images, five use the miniaturist style to depict newsworthy current events from the Middle East and five use quilt-like blocks of Persian decorative patterns to build up images of the U.S. Capitol building, the Colosseum, a “McMansion” amalgam, the sinking Costa Concordia and the last remaining maritime signal station in America — the 1807 Portland Observatory.

This last group of works in particular underscores how using any particular style creates a perspective with an implied history or ideology. Next to the Roman Colosseum, the U.S. Capitol appears not only as Western “other” but rather aptly as the beacon of republicanism. The “McMansion” image takes full advantage of the implied repetitive endlessness of the decorative patterns.

The 2010 paintings, however, could hardly be more different than the coolly post-modern pictures. They feel genuine in part because of the awkwardness of the painting but also because there is nothing ironic, critical or witty about them.

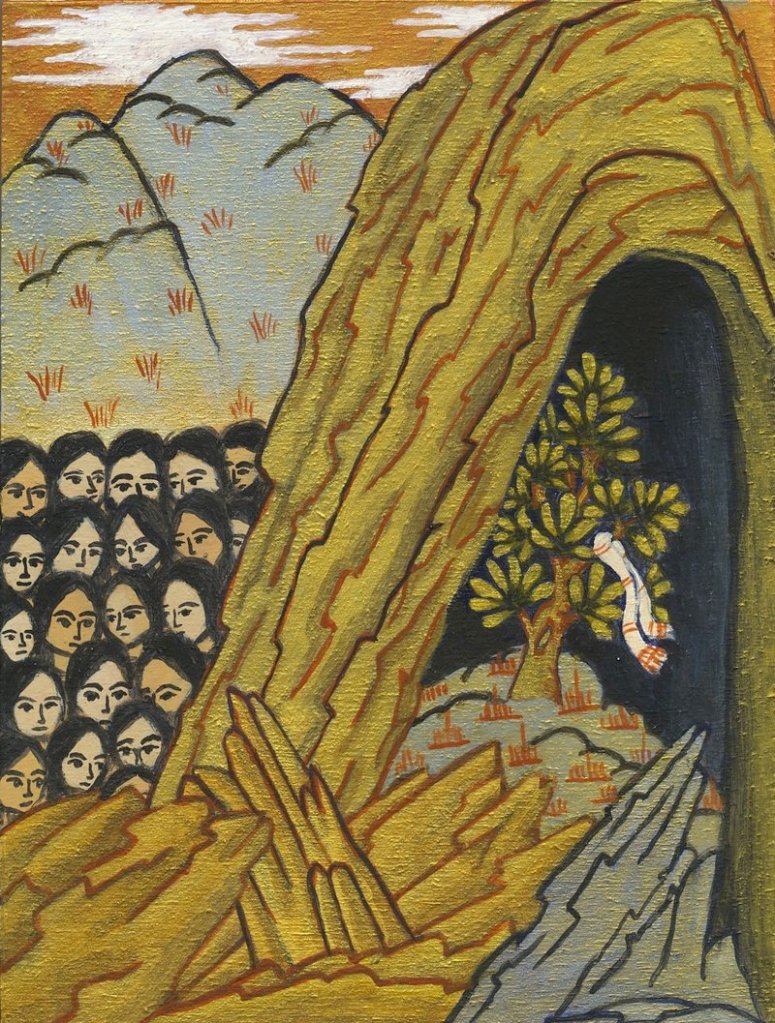

I was particularly intrigued by “Waiting.” Of the earlier pieces, it has the strongest miniature style. It shows a sea of stylized women looking onto the scene in which a tree grows inside of a cave. It’s a hauntingly strange image, but also one non-Muslims have a chance of recognizing: It’s the Cave of Thor in which Mohammad hid for three days and in which miraculously sprang up an acacia tree.

The tree in the stylized cave immediately gives the scene an iconic feel that jolts you into trying to recognize it. A scarf left on a branch hints of past human presence, and the onlookers create the idea that something important has happened.

When I saw the title and the throng of women, what first came to mind is the Iddah — the scripted period of mourning during which a widow cannot take a new husband. In the context of the show, this makes sense (read: war widows). I doubt it’s what Gallo intended, but her creative handling of the scene opens this kind of door.

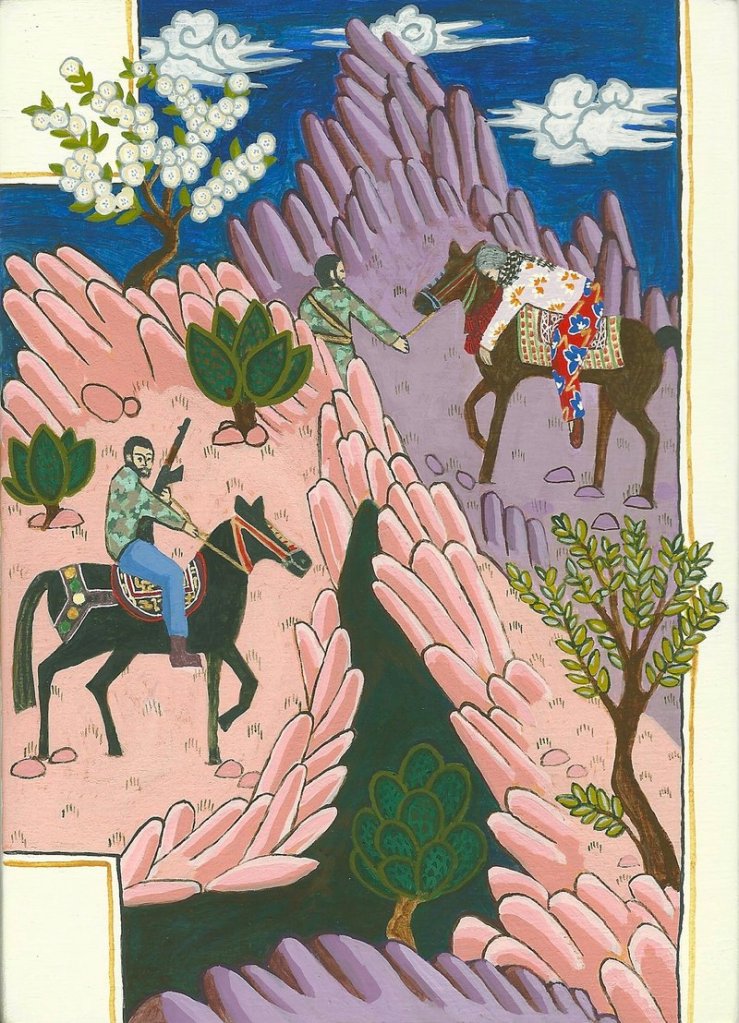

“Last Supper” is an image from the published account of New York Times photographer Tyler Hicks. The traditional style and classical subject might be invisible if not for the context of the show.

Gallo employs an illustration tool by later showing Hicks bringing his colleague’s body (Anthony Shadid) to Turkey in “Out of Syria.”

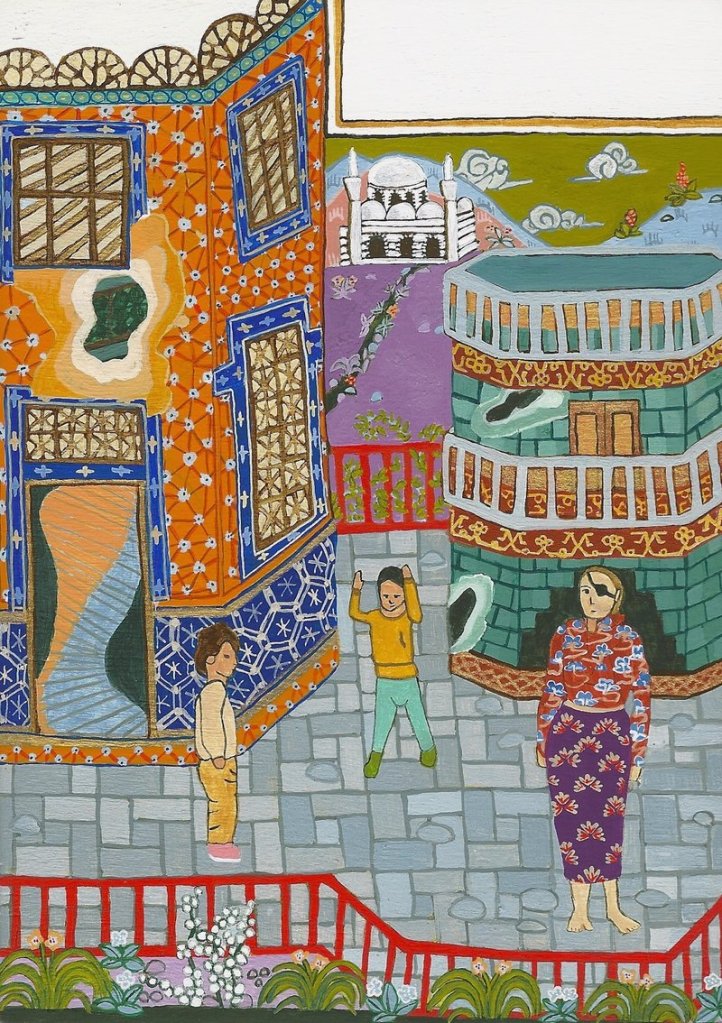

“The Destruction of Homs” depicts journalist Marie Colvin and several children in a shell-pocked but otherwise idyllic urban setting before they were killed.

Gallo’s adopting the point of view of Western journalists is particularly interesting. Maybe they were the simplest sources, but matching their tales to a classical technique used for historical and religious texts makes some significant ripples in the pool we usually use as a mirror.

Are these historical events, or examples of the eternal narcissism of those telling the stories thinking that they are the story? Whereas we used to hear from historians, scholars, priests and kings, we now hear from journalists.

One of the images shows Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi immolating himself in an act widely seen as kick-starting the Arab Spring uprisings. Heavy on well-handled traditional conventions of Muslim manuscripts, it seems to show a major historical moment.

“Rising” raises far more questions than it answers, but the perspectives it presents are richly rewarding. Witnessing Gallo’s mastery of her technique and the pictorial conventions over time is impressive as well as enlightening.

Finally, as worldly as the scope of the work is, Gallo never loses sight of our perspective. This is why it is art rather than cultural critique or simple illustration. And it is why “Rising” is worth seeing.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.