In Rufus Coes’ “Coastal Route” at Elizabeth Moss Galleries in Falmouth, there are two paintings of plain boxes.

One, an open and seemingly appreciated-until-empty case of Budweiser, doesn’t purport to contain any mystery. It’s a prosaically realistic watercolor, impressively stark and textured with dry-spackled drops. It sits on a slate gray porch in colorlessly silver sun in front of an open doorway’s impenetrably dark-washed space.

The other is an acrylic painting of an Utz potato chip box handled with an ironic blend of clearly rendered textures and unexpectedly soft focus (which lends a strange, dream-like quality). The box is well-worn, and its corners are softened by long use and heavy contents.

This box looks so commonplace at first glance as to be strangely literal. But natural curiosity leads us to ask why Coes painted it.

“What’s in the box?” came first, but soon I wondered if the piece has more to do with the nationally obvious precedent of Andy Warhol’s boxes or the more local precedent of Jamie Wyeths’ paintings of chickens nesting in boxes. Wyeth was one of only two artists allowed to have a studio in Warhol’s Factory, and his repurposed chicken-house boxes constituted a response to Warhol: A boxing match, if you will.

Coes is playing a similar game, and ultimately sides with Wyeth’s conclusions of skilled style and personal experience over Warhol’s abstractly sophisticated economic cultural machinations. I don’t necessarily agree with Coes, but I am impressed by his intelligent engagement (conscious or otherwise) with such a debate.

Coes basically paints with Edward Hopper’s softly understated and coolly distant mid-century modernism while he makes watercolors like the Wyeths — driven by observational virtuoso rather than flashy technical conventions.

The dryly textural watercolors feature found objects, while the studio paintings generally engage narratives scripted by the artist.

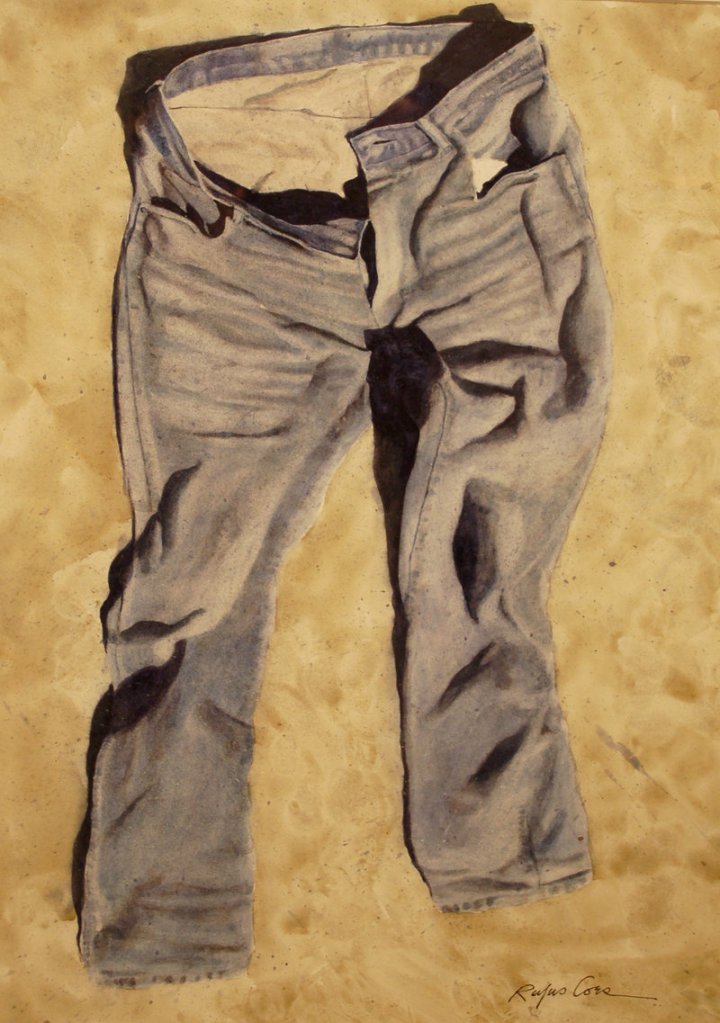

Coes’ oil painting of a white shirt on a hanger dangling from a nail doubles down with its neighbor, a watercolor of blue jeans laid out on a beach. Both are exceedingly spare and well-painted, and articulate themselves through puzzlingly different textures.

The oil “Dish Towel” is just a slightly crumpled towel seen straight on. However, if stretched tight, it could pass for an abstract, striped painting.

Its soft focus either pushes you away to resolve the blurriness or pulls you in so that you are past the rendered focus and close enough to see the actual brushwork. It’s an unusual feat for a painting, and a brilliant joke about the push-pull effect of painting championed by Hans Hoffmann.

“Linda Marketing” depicts a woman crossing a street with a grocery bag in her hand. At first glance, it looks simple and Hopper-esque. But it’s hardly simple. This fascinating oil dates to when potatoes were 99 cents for 20 pounds and knit wrap dresses were all the rage.

Linda is a looker, but she’s looking away — looking both ways, in fact, before crossing the street. That gives the viewer the chance to gaze at her unblinkingly (the title hints she’s fine with that). You are in the car reflected straight across the street.

But something isn’t right: Linda’s reflection in the window behind her is to the right, as though we were off to her right instead of placed solidly in the lower left of the painting where the car reflection and perspective place us. (We line up with the 1940s truck grill on the left, and look up at Linda.)

The conflicting reflections could simply be a mistake, but they deliver tension worthy of Andre Debus. It feels like that moment when choosing to stay or drive off has made all the difference.

Coes is a mature painter with a settled touch. He has a genuine fondness for musical intervals, modes and rhythms. He is quirky to the core, but almost absently so; in fact, it’s not clear if he is simply honest to the point of primitivism or if he enjoys messing with us for ironic effect.

I don’t like Coes’ overly stylized wave paintings, but on the other hand, I think his bivalve shell drawings are brilliant — yet again, oddly so with their stone soup simplicity.

Coes has been around for a long time, but this is the first solo show I have seen of his work. It is quietly odd, and intriguingly challenging.

PAIRED WITH “Coastal Route” is a retrospective of watercolors by the late Ethel Halsey Blum (1900-91) mounted as a benefit for her namesake gallery at the College of the Atlantic.

The solid watercolors appear as a rather worldly group of travel sketches. Their range is dizzyingly impressive: Nassau, Thailand, Provence, New York City, Tucson and then comfortably less exotic scenes of Connecticut and Maine.

It’s an unusual show for a gallery, because it has the curatorial and historic chops of a museum show.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.