Some shows strike me as compulsory, and they get reviewed. Others strike me as major efforts of their type, and they get reviewed too. A third category offers me personal enhancement, and I sometimes write about them.

A final group floats in from out of the blue. Catalogs, announcements, requests and notes from informed people nudge me in its direction and, sometimes, to pay dirt.

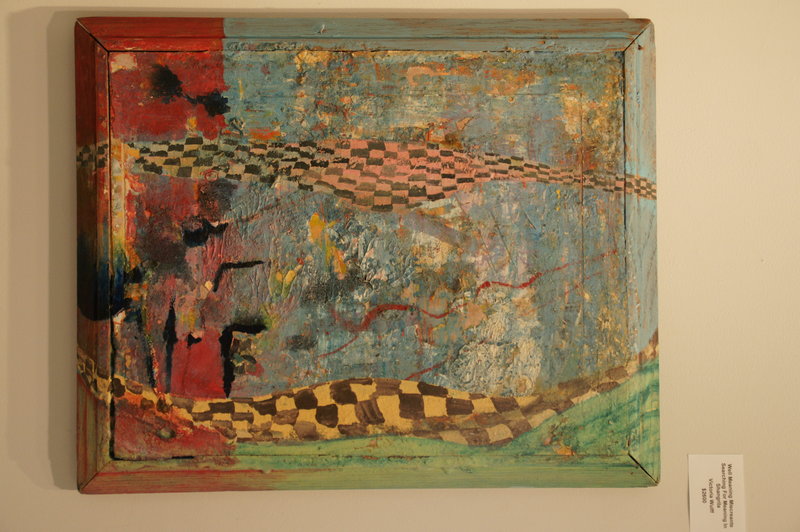

Take the paintings of Victoria Wulff at Studio 53 in Boothbay Harbor as an example of the last breed. An email from an old prior-to-email friend introduced Wulff as an “original, intuitive and very painterly” artist. I’ve seen the show, and I concur. Her work is original, obviously intuitive and fluid. It is also mystical, seductive in its narration, and often presented as a seat at a performance.

Work of its kind does not find itself into Maine galleries easily, and the closest in sympathy that I can suggest are the paintings of Robert Hamilton. Like Hamilton, Wulff stages ongoing dramas in faraway places, gives them imponderable titles and can be lightly notational in form. Here, too, the drama can end, to be replaced by another or by nothing. It is all ephemeral.

The sense of ephemerality is accentuated by Wulff’s extension of the painted narrative beyond the bounds of the canvas, up onto the beveled surfaces of her frames and then allowing it to float off into space. The frame does not enclose or furnish the work; it either enlarges it or acts as a conduit on its behalf.

In works such as “Refugio” and “Isolas,” the viewer is able to maintain a sense of reality when confronting dream-altered Italian landscapes. But in “Well Meaning Miscreants Searching for Meaning to Shangrila” and “The New Dawn Ambassadors,” the image is abandoned to the surreal.

In the latter — a study in black, white and gray — a great landscape has been vacated to indistinct dog-like forms that are made allusive, more suggested than formally expressed. But they very clearly possess the world to its rocky edges.

It’s a pleasure to see invention and fantasy offered so candidly and without elaborate philosophic justification. This show does not have a formal title, but “The Altered World of Victoria Wulff” would fit nicely.

“ACCORD” IS MAKING its eighth appearance at the George Marshall Store Gallery in York. Its special blending of fine arts with the decorative arts has given it longevity when similar efforts by others have failed.

The usual fine arts/objects exhibition is a field day for decorators, and doesn’t deserve to survive. I can say this because my passions extend to anything good you can cram into a house, fine or not. In the resulting melee, the fine arts have to struggle, and the furniture usually wins out.

And so it is with fine arts/objects exhibitions. The good pictures — if there are any — are apologetic. They don’t belong, and they know it.

The archness of this declaration does not apply to the “Accord” dynasty. In its seven previous manifestations — this one is formally titled “Accord VIII” — the show established itself as a polite flirtation between bygone vernacular culture and modern art. It sought out visual parallels between the 18th- and early 19th-century physical culture of Maine and the imagery of contemporary regional artists.

It didn’t propose a discourse between an 18th-century black banister back side chair and the slashes of geometric modernism, and didn’t imply that Maine painters were even aware of such chairs. It was content to show a parallel of attitudes — the discipline of early Calvinist Maine and, say, the discipline of intellectualized modernism. At least, that’s what I came away with.

It was able to do this with panache, because it had the bounty of the Museums of Old York’s Collection to draw upon. Its chambers are one of the treasures of Maine. Whether that trove provided the inspiration or whether the art probed the collection I cannot say, but I’d guess the latter. They were art-oriented shows displayed in tiny austere spaces, and utterly charming.

“Accord VIII” has a similar format, but its basis is not solely Colonial or post-Colonial Maine, and is more object directed than fine art directed. The objects are not extracted from Old York, but rather from antique dealers along lower coastal Maine.

And so the gates have opened, and among the svelte old sideboards and highboys have come floor lamps from the 1930s and 1940s, a terrific lawn sprinkler from the same period, a beautiful small cabinet with Japanese overtures from the late 19th century, a prickly-looking device for holding tools that reminds me of one of the great mosques of Mali, bits of architecture, a Southwestern horn chair, a late weathervane and the like.

While the flow is still mainly 19th-century American, the range of material has warmed the show to some more emotionally demonstrative painting, and has given curators Tom Johnson — here, a guest — and Mary Harding a wider range in which to suggest pairings.

I note the non-related but distinguished work of ceramic artist Maureen Mills in the lower gallery at the Marshall Store. It will be on exhibition through Sept. 30.

THE ELEVATION OF PHOTOGRAPHY into the realm of the arts is an oft-told tale. It has to do with the crossing of an imaginary dividing line once so firmly embraced by critics that, as one said, “the worst painting possible and the best photograph possible” fell on opposite sides of that line.

It wasn’t that photographs didn’t have aesthetic merit; it was the fact that they were made with a technologic instrument called a camera and not with a brush or a burin.

The story of photography’s legitimization can be told in various ways. One enchanting account is “Making a Presence,” an exhibition at the Bowdoin Museum of Art in Brunswick. Its subtitle, “F. Holland Day in Artistic Photography,” introduces its principal character, Day (1864-1933). It is also a particularly apt event for New England.

Day was wealthy, cultured and ultra-sophisticated, and flourished in Boston. I suppose we should grant him the approbation of Renaissance man. He was a critic, a writer on the arts, a committed bibliophile, a publisher of good and handsome books, and one of the significant photographers of his time.

Day’s efforts on behalf of the acceptance of photography are, in effect, told in the 80-plus images at Bowdoin. Some are by him; more are of him. Of the latter, many were made by some of the most distinguished photographers of his era.

To put a finer point on it, in December 1902, Day presented an exhibition in his Boston studio titled “Portraits by a Few Leaders in the Newer Photographic Methods.” The leaders totaled 21 and included Edward Steichen, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Clarence White, Gertrude Kasebier and Frederick Evans. Their works totaled 54.

It is assumed that Day supplemented the event with work of his own. Among other things, each of the 54 prints by the invited artists were portraits of Day. He was there in Algerian costume, in robed medieval costume, in some kind of darkroom regalia and in other guises. He was also there as an artist, as a man of deep solitude, as an elegant connoisseur and more.

Images from Day’s 1902 show make up the central portion of the show at Bowdoin. It is an astonishing performance, and raises so many thoughts about the man himself that the viewer is apt to lose sight of the importance of Bowdoin’s show.

The intent of the event is to present a large and richly selected group of photographs by accomplished artists committed to the doctrines of pictorial photography.

They clearly descend from paintings of bygone ages, from Victorian sentimentality, from the urge to idealize, from a sense that adding allegory adds weight, and from a conviction that making images that are softly focused or even slightly out of focus gives them philosophic intensity.

We washed ourselves of all of that a decade or so before Day died, and embraced straight or modernist photography in its place. Bowdoin suggests we take another look — a look at great craftsmanship under basic conditions, at beautiful imagery for beauty’s sake, at a sense of mission and — for the wistful — glorious printing in heroic platinum.

This show is a beautiful and idiosyncratic aesthetic adventure.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 47 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.