Oscar-winning actor Henry Fonda was a haunted man? The distinctly American characters he played in films and on stage — young Abraham Lincoln, Tom Joad, Wyatt Earp, Mister Roberts, the president of the United States — certainly dealt with their share of ghosts. But Fonda himself?

Self-destruction, if not specters, did seem to trail Fonda.

His wife Frances killed herself, and a former wife, actress Margaret Sullavan, may have ended her own life as well. The author of the novel “Mister Roberts,” which led to Fonda’s Broadway triumph, committed suicide. There’s even the possibility that it wasn’t an accident in 1935 that put Fonda, his film career under way, in a garage and at the wheel of a car, its engine running.

Fonda appears to have been drawn to real people and fictionalized characters who destroy themselves or cannot resist a path toward death. To ascertain why, author Devin McKinney relies heavily on books by Fonda and children Peter and Jane as he explores the actor’s psyche.

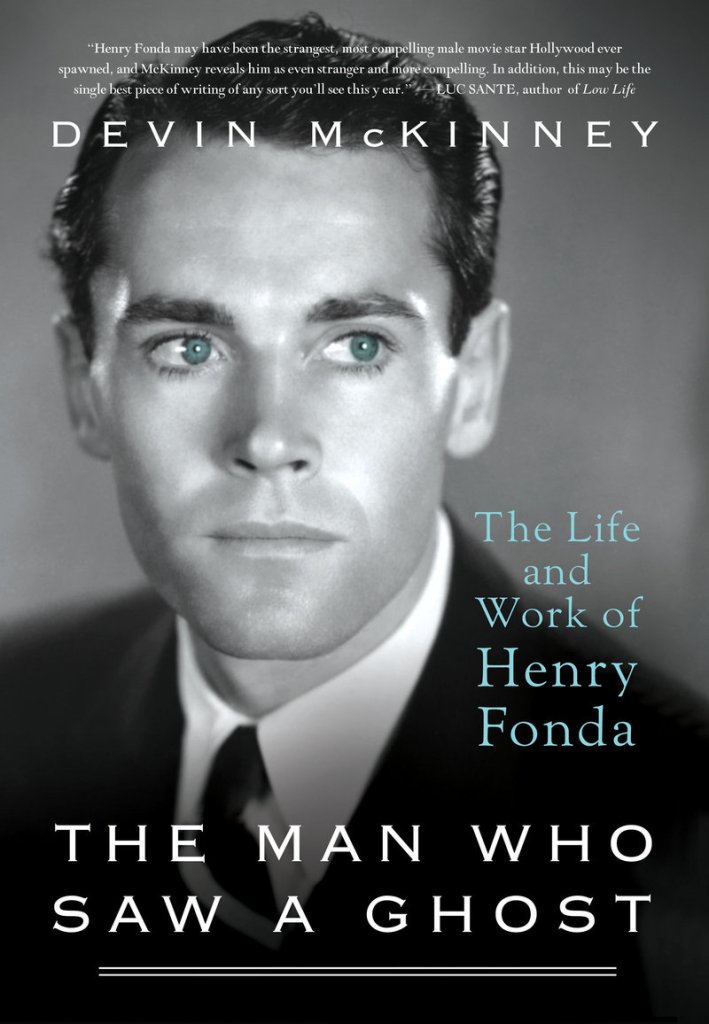

“The Man Who Saw a Ghost” is as unusual and intriguing a Hollywood biography as its title suggests. Fonda has long been described as a cold, emotionally distant father and self-centered husband — he was married five times. McKinney is less interested in Fonda on the set than trying to explain the man and the masks he chose to wear for the public’s amusement.

McKinney’s narrative often carries the tone of a psychiatric report — grave, humorless and bent on connecting Fonda’s off-screen actions to his on-screen work. Sometimes, McKinney gets lost in the actor’s head in his search for meaning. Yet, he can be persuasive.

For example, McKinney argues that Fonda’s role in “The Wrong Man” as an innocent musician whose incarceration drives his wife insane is uncomfortably reminiscent of wife Frances’ mental decline.

McKinney also sees Fonda’s role in the play “A Gift of Time” — the protagonist kills himself rather than continue a slow death from cancer — as his way of dramatizing “an obligation” to his late wife and achieving some kind of understanding.

Still, as Freud might have said, sometimes a role is just a role, especially when an actor is under contract to a studio, seeking a challenge or just out to make a dollar. McKinney is on firmer ground when he cites Fonda’s efforts to see to the screen the anti-lynching Western, “The Ox-Bow Incident” and the court drama, “12 Angry Men.”

Those two films connect better than others to the big reveal in McKinney’s psychiatric portrait, the ghost that might explain how Fonda lived: At 14, he saw the lynching of a black man in his hometown of Omaha, Neb.

“It suggests the seeds of so much sorrow, anger and solitude in Fonda,” McKinney writes. But he says it’s only context, not an explanation. “All we may claim is that it happened, and all we may justifiably imagine is that a boy witnessed it, remembered it, and carried it with him through all the years of a long, difficult, meaningful, magnificent American life — until he too was dead, his bones burned, his body released from all pain, all memory, ashes to ashes.”

Overwrought prose aside, McKinney offers a unique portrait of an actor who hid so much emotionally but trusted his audience to see what he couldn’t show them.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.