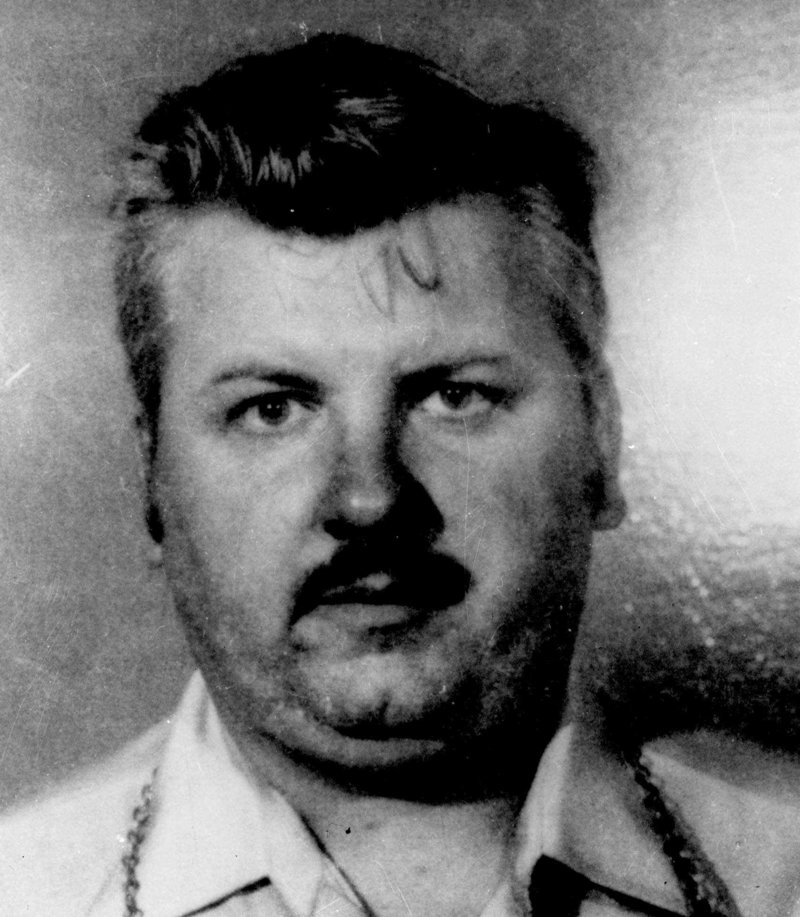

CHICAGO – Detectives have long wondered what secrets serial killer John Wayne Gacy and other condemned murderers took to the grave when they were executed — particularly whether they had other unknown victims.

Now, in a game of scientific catch-up, the Cook County Sheriff’s Department is trying to find out by entering the killers’ DNA profiles into a national database shared with other law-enforcement agencies. The move is based on an ironic legal distinction: The men were technically listed as homicide victims themselves because they were put to death by the state.

Authorities hope to find DNA matches from blood, semen, hair or skin under victims’ fingernails that link the long-dead killers to the coldest of cold cases. And they want investigators in other states to follow suit and submit the DNA of their own executed inmates or from decades-old crime scenes.

“You just know some of these guys did other murders,” said Jason Moran, the sheriff’s detective leading the effort. He noted that some of the executed killers ranged all over the country before the convictions that put them behind bars for the last time.

The Illinois testing, which began in the summer, is the latest attempt by Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart to solve the many mysteries still surrounding one of the nation’s most notorious serial killers. Dart’s office recently attempted to identify the last unnamed Gacy victims by exhuming their remains to create modern DNA profiles that could be compared with the DNA of people whose loved ones went missing in the 1970s, when Gacy was killing young men.

That effort, which led to the identification of one additional Gacy victim, led Dart to wonder if the same technology could help answer a question that has been out there for decades: Did Gacy kill anyone besides those young men whose bodies were stashed under his house or tossed in a river?

“He traveled a lot,” Moran said. “Even though we don’t have any information he committed crimes elsewhere, the sheriff asked if you could put it past such an evil person.”

Dart’s office said Monday that it believes this is the first time DNA has been added to the national database for criminals executed before the database was created.

“This has the potential to help bring closure to victims’ families who have gone so long without knowing what happened to their loved ones,” Dart said in a news release.

Receiving permission to use the database posed several challenges for Dart’s detectives.

After unexpectedly finding three vials of Gacy’s blood stored with other Gacy evidence, Moran learned the state would only accept the blood in the crime database if it came from a coroner or medical examiner.

Moran thought he was out of luck. But then the coroner in Will County, outside Chicago, surprised him with this revelation: In his office freezer were blood samples from Gacy and at least three other executed inmates, all of whom had been put to death there in the period after Illinois reinstated the death penalty in the 1970s. The executions were carried out between 1990 and 1999, a year before then-Gov. George Ryan established a moratorium on the death penalty.

So it was the Will County coroner’s office that conducted the autopsies and collected the blood samples.

That was only the first obstacle.

The state sends to the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System the profiles of homicide victims no matter when they were killed. But it will only send the profiles of known felons if they were convicted since a new state law was enacted about a decade ago that allowed them to be included, Moran said.

That meant the profile of Gacy, who received a lethal injection in 1994, and the profiles of other executed inmates could not qualify for the database under the felon provision. They could, however, qualify as people who died by homicide.

“They’re homicides because the state intended to take the inmate’s life,” said Patrick O’Neil, the Will County coroner.

Last year, authorities in Florida created a DNA profile from the blood of executed serial killer Ted Bundy in an attempt to link him to other murders. But the law there allows profiles of convicted felons to be uploaded into the database as well as some profiles of people arrested on felony charges.

Florida officials said they don’t know of any law-enforcement agency reaching back into history the way Cook County’s sheriff’s office is.

“We haven’t had any initiative where we are going back to executed offenders and asking for their samples,” said David Coffman, director of the Florida Department of Law Enforcement’s laboratory system. “I think it’s an innovative approach.”

O’Neil said he is looking for blood samples for the rest of the 12 condemned inmates executed between 1977 and 2000. So far, DNA profiles have been completed on the blood of Gacy and two others.

Among the other executed inmates whose blood was submitted for testing was Lloyd Wayne Hampton, a drifter executed in 1998. Hampton’s long list of crimes included some outside the state — one conviction was for the torture of a woman in California. But shortly before he was put to death, he claimed to have committed additional murders but never provided details.

So far, no computer searches have linked Gacy or the others to other crimes. But Moran and O’Neil suspect there are investigators who are holding aging DNA evidence that could help solve them.

That is what happened during the investigation into the 1993 slayings of seven people at a suburban Chicago restaurant, during which an evidence technician collected and stored a half-eaten chicken dinner as part of the evidence. There was no way to test it for DNA at the time, but when the technology did become available, the dinner was tested and revealed the identity of one of two men ultimately convicted in the slayings.

Moran wants investigators in other states to know that Gacy’s blood is now available for analysis in their unsolved murders. He hopes those jurisdictions will, in turn, submit DNA profiles of their own executed inmates.

“That is part of the DNA system that’s not being tapped into,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.