BUTLER, Pa. – Four hundred miles from Sandy Hook Elementary, a Pennsylvania superintendent named Mike Strutt left a morning meeting on Dec. 14 and decided to place his schools on “threat alert.” He was concerned about a copycat attack on the day of the Connecticut shooting. But, as he read reports of the massacre, he started to worry more about something else.

For 20 years he had specialized in school safety, filling three binders with security plans and lockdown drills – all of which felt suddenly inadequate. In the case of an attack, would a “threat alert” do him any good?

He looked out his office window at the snow-covered trees of western Pennsylvania and imagined a gunman approaching one of Butler County’s 14 schools, allowing the attack to unfold in his mind. In came the gunman past the unarmed guards Strutt had hired after Columbine; past the metal detectors he had installed after Virginia Tech; past the intercom and surveillance system he had updated after Aurora.

Strutt stood from his desk and called the president of the Butler County School Board, Don Pringle.

“This could happen here,” Strutt said. “Armed guards are the one thing that gives us a fighting chance. Don’t we want that one thing?”

That question has preoccupied schools across the country since 27 people died in Newtown, Conn., last month, and the emerging solutions reflect the nation’s views on gun control. In a divided America, guns are either the problem or the solution, with little consensus in between. A dozen states have proposed legislation to put armed guards in schools; five others have drafted plans to officially disallow them.

Groups in Utah are training teachers to carry their own guns, Tennessee is hiring armed “security specialists” for $11.50 an hour and the National Rifle Association is working on a plan to arm school volunteers even as teachers gather in protest outside the group’s headquarters.

At stake in the debate are basic questions about the future of gun control in the United States. Do guns in schools assuage fears or fuel them? Do they keep students safe or put them at risk?

Here in Butler, a shale-mining town in the woodsy hills north of Pittsburgh, Strutt and the school board decided their reaction to Newtown could allow for neither hesitation nor ambiguity. No local school had ever experienced a gun-related threat, but neither had Sandy Hook Elementary. The district was running on a $7 million deficit, but some priorities demanded spending.

The school board worked out details with a solicitor, who submitted a proposal to a judge, who came into work on a Sunday to sign an emergency order. Before the first funeral began in Newtown, Butler’s head of school security began calling retired state troopers to ask two questions with major implications for the future of public education:

Did they own a personal firearm?

Would they be willing to carry it into an elementary school?

Frank Cichra owned a gun that he was willing to carry, so he arrived early last week at a shooting range in the mountains outside Butler, hoping to qualify as an armed school policeman. He wore snow boots, a heavy jacket and earmuffs that doubled as ear protection from the cracking sound of gunfire. He slipped on gloves and cut the black fabric away from his right index finger.

“Won’t hit the target unless I can feel the trigger,” he said.

He loaded the magazine of his .40-caliber Beretta as a half-dozen other men arrived at the range. Like Cichra, they all were retired Pennsylvania state troopers who had been recruited as guards.

Butler County had cut 75 teaching and administrative positions in the last five years because of a shrinking budget, but now the district of 7,500 students couldn’t hire armed guards fast enough. It had added a new insurance policy and $230,000 to the annual security budget in order to arm and employ at least 22 former state troopers – enough to station at least one guard at each school and every after-school event. In a town where hunting guns hung on the wall of the prosecutor’s office and the rifle team won championships, the decision to arm guards had elicited a single protest. One family boycotted school for a day before returning the next.

The district’s hiring requirements for guards were at once simple and absolute: only retired state troopers with 20 years of experience who owned a gun and could pass a 60-round shooting test.

Cichra, 46, paced in the snow to keep warm and watched the first few troopers begin the test. He had been retired for exactly seven months on the day of the shooting in Newtown and that had felt like long enough. He couldn’t stand watching TV. Home improvement bored him. He had spent four years in the Army and 21 more on patrol – a career built on the hard reality of “good guys versus bad,” he said, and Newtown offered him another mission. He had three kids, ages 5, 14 and 17, attending schools near Butler.

“We might not like it, but the modern reality is our kids are vulnerable, and they need our help,” he said. “Nobody’s doing this job for money.”

In front of him on the range was a trooper who had retired four days earlier because he thought the school district needed him and another who had just spent $600 to buy his first personal weapon, a Glock, so he would have a gun with which to qualify. Smoke rose from the targets and the smell of burnt powder filled the air.

The first group of shooters rotated out, and Cichra holstered his Beretta and took his position on the range. The instructor explained that the test was meant to simulate a firefight – “a worst-case scenario,” he said. Cichra would be asked to shoot with one hand and then with two; while kneeling and while standing; while walking backward and while moving toward the target. “Listen to me and focus on the threat,” the instructor said. “Imagine you are closing in on the shooter.”

Cichra took aim at a silhouette target from 25 yards.

“Fire!” the instructor yelled, as gunshots echoed off the mountains.

Fifteen yards.

“Hit his chest,” the instructor shouted.

Seven yards.

“Kill shot.”

Two yards.

“He’s wearing a vest. Aim for the head!”

Cichra fired his last round and holstered his weapon. The instructor studied the mangled target and counted his score. Cichra had been shooting guns for most of his life. He needed to score a 226 out of 300 on the test to qualify as an armed school guard. The instructor came back with a score sheet.

Sixty shots fired. Fifty-nine to the chest and one to the head.

“A real marksman,” the instructor said.

He had scored a perfect 300.

That qualified him to carry his Beretta to work the next morning at Summit Elementary, a single-story school of about 200 students located amid the shale mines and snowfields on the edge of town. Cichra arrived early and turned on a metal detector at the front entrance. He loaded one bullet into the chamber so he could fire instantaneously in case of an attack and 11 more into a magazine. He sat at a desk facing the glass doors, his eyes scanning the parking lot. A sergeant had told him once that a good state trooper operated like a traffic light on yellow, always on edge, anticipating whatever might come.

In came a boy, 8, tripping over his untied shoelaces. “You’re going to fall and hurt yourself, son,” Cichra said.

In came a boy, 6, with crayons spilling out his pocket. “Let me get those for you,” Cichra said, bending over to collect them.

In came a girl, 10, carrying her backpack though the metal detector, which set off the alarm. “I’m sorry,” she said. She handed Cichra her pink binder and her lunch bag. He opened it and sifted through the contents inside. String cheese. Goldfish. Chocolate milk. “Looks good,” he said, handing the bag back to the girl. “Looks tasty.”

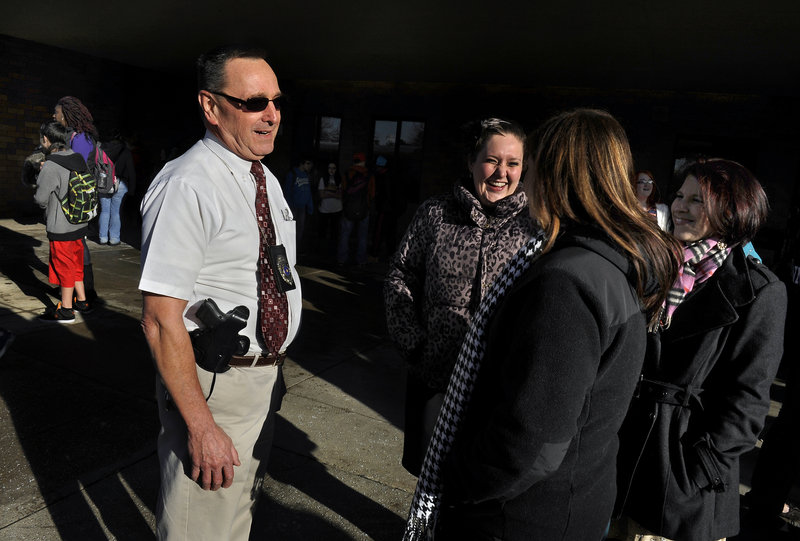

He had decided the best way to carry a gun in an elementary school was to act nothing at all like a person carrying a gun. A few of the other school guards in Butler wore old police vests and displayed guns on their hips, but Cichra dressed in reading glasses, khaki pants, a collared shirt and a sweater that covered up his Beretta. He sat by the entrance, reading a newspaper and studying attendance lists so he could memorize students’ names. Whenever one walked by, Cichra stretched out his right hand to give a high-five. “Hit me,” he said, until his palm turned red and a teacher stopped by to offer hand sanitizer.

“We usually think of germs as our number one threat,” the teacher said.

Every few hours, Cichra made coffee in the faculty lounge and then patrolled the school’s two long hallways, stopping along the way to admire the first-graders’ cardboard gingerbread men that decorated the walls.

Every once in awhile, a student approached him to ask a question. Did he carry a gun? Did he have any secret weapons like Batman? Did he have an extra badge to give away?

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.