Weather forecasters use a vast array of technology, from satellites above the clouds to supercomputers below, but they still hedge their bets when it comes to saying how much snow will fall in a big storm, like the one expected Friday.

A forecast from just a few weeks ago shows why: The computer models were in agreement that an area of low pressure called a “Norlun trough” would occur, and a swath of southern Maine would likely get a foot of snow or more.

But the models were wrong. The trough largely fizzled and only a few flakes fell.

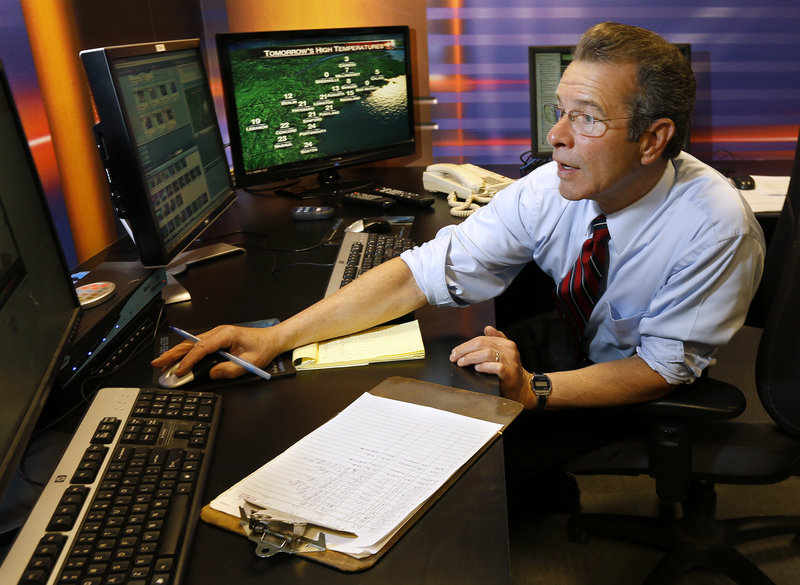

“The Norlun trough burns a lot of people,” lamented Kelly LeBrecque, a meteorologist with WCSH-TV in Portland.

That blown forecast, meteorologists said, illustrates the possibilities and perils of using the computer models that are now the basis of many weather forecasts.

Although more specialized computer models can enable forecasters to warn people of severe weather well in advance, Mother Nature still throws curveballs that can bedevil even supercomputers.

“All models are wrong at times, and sometimes it’s deciding which one is going to be less wrong,” said Mark Parquette, a meteorologist with Accuweather, a commercial forecasting firm in State College, Pa.

Still, those models drive most weather predictions. They rely on supercomputers to crunch hundreds of weather observations from around the globe, comb thousands of past patterns and come up with an outlook for where storms will develop and where they will go.

“One of the more challenging parts of being a meteorologist is looking at the information (produced by the models) and interpreting it,” said John Jensenius, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Gray.

The two most popular models for meteorologists are the U.S. model, developed by the National Weather Service, and the European model, developed by a consortium of weather agencies in European countries.

Dozens of other models have been created by other countries, researchers and universities, and each has strengths and weaknesses.

For Friday, the U.S. and European models agree that a system moving through the Midwest and another in the Southeast will combine off the mid-Atlantic coast and produce a strong storm in Maine.

Parquette said the European model first forecast a significant storm about five days ago. The U.S. model hit on it a day or so later, and both now forecast heavy snow.

How much snow?

Parquette’s company said more than 12 inches. Jensenius and his colleagues at the weather service said 18 to 24 inches are possible. WCSH-TV puts Portland on a line between 12 inches and more than 15 inches.

Although the predictions vary, people are paying attention. Most high school sports events that were scheduled for Friday night are being moved to Thursday night, so the games can be played before the storm.

The Portland Pirates hockey game scheduled for Friday night in Providence, R.I., has been moved to Monday night.

LeBrecque said that kind of impact always makes her cautious about making snowfall estimates too far in advance of a storm.

She looks at models, she said, and pays a lot of attention to how they have performed in the last few days.

“You look at the trends and which ones are all over the place and which ones are more consistent,” LeBrecque said. “Then you try to meld them all together and make your own.”

Parquette and Jensenius said models have distinct personalities that forecasters must take into account.

For instance, the U.S. model has a tendency to forecast storms moving across the country faster than they usually move. The European model often underestimates how strong a storm will become.

But even knowing that doesn’t remove the human element, Parquette said.

“Sometimes, it’s not easy to predict which bias will happen,” he said, and forecasters must apply their experience.

People think that with all that data, forecasters must be able to make accurate predictions, but Parquette said a lot of sorting must be done, so the true picture often doesn’t emerge until the last minute.

For instance, Friday’s storm could form slightly east of the forecast position, and even 50 miles can throw off accumulation forecasts by half a foot or more.

That’s why all those models must be looked at and analyzed, Parquette said, even if it occasionally seems like too much.

“There’s almost a glut of different weather models, and at times it’s like data overkill,” he said. “But I’d rather have too much information than too little.”

Still, he said, some of the most important input comes from the gut.

“Forecasting is more of an art than a science sometimes,” Parquette said. “It’s a feel.”

Edward D. Murphy can be contacted at 791-6465 or at:

emurphy@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.