“Whoever plays, sings or renders ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ in any public place, theater, motion picture hall, restaurant or cafe, or at any public entertainment other than as a whole and separate composition or number, without embellishment or addition in the way of national or other melodies, or whoever plays sings or renders ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ or any part thereof as dance music, as an exit march, or as part of a medley of any kind shall be punished by a fine of not more than one hundred dollars.”

I came across this gem of Boston law while reading articles on Stravinsky during this centennial of “The Rite of Spring.”

My first thought was, eureka! Now we’ve got them, all the singers at baseball and football games who like to show off just how much they can “embellish” the song while still retaining a slight vestige of its original melody.

It has gotten to the point where anyone who sings the tune straight is regarded a novelty. It would be different if the pop artists (and even opera stars) were trying to make it more compelling, but they’re not. Maybe it’s just that they’re trying to disguise wrong or unreachable notes in a difficult composition.

Unfortunately, it seems there has been only one instance of the ordinance’s application — against Igor Stravinsky on Jan. 15, 1944, about the time I belted out the song from the balcony before a performance of “Oklahoma!” in New York. (My father told me it was on opening night, but that would have been in 1943.)

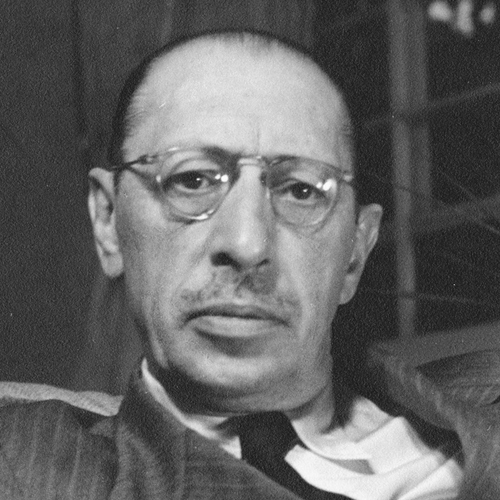

I mention that incident only to illustrate the unreliability of hindsight, which has perpetuated the myth that Stravinsky was actually arrested, complete with a mug shot (taken of a look-alike criminal four years earlier).

In reality, Stravinsky wrote his arrangement of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in token of his appreciation of his adopted country. It includes contrapuntal counter-subjects and a modulation into the subdominant by means of a “blue note” — a passing seventh. (The original version has been recorded.)

After the first performance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, some concerned citizen phoned the police to complain, and they attended the second performance en masse.

Stravinsky, however, had been tipped off, and played the work straight. The 14 policemen are said not to have remained for the rest of the concert, which included some of Stravinsky’s latest compositions, including the “Circus Polka.”

Stravinsky’s reaction to the peculiarities of his adopted country has not been recorded. It probably took the form of an extra vodka martini.

The composer’s musical taste, in this instance, leaves something to be desired, since he referred to “The Star-Spangled Banner” as “a beautiful sacred anthem.” The tune, of course, is that of a risque British drinking song, “Anacreon in Heaven,” which doesn’t even fit Francis Scott Key’s verses very well.

It caught on after 1865, when it was played at the restoration of the flag to Fort Sumter (not Fort McHenry) and later was taken up by John Philip Sousa, who made it popular. It was named the official anthem of the United States by Congress in 1931, just before Sousa’s death.

A phrase from the anthem, “In God is our trust,” inspired Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase to put “In God We Trust” on the dollar bill during the Civil War.

So next time the Patriots play in Gillette Stadium, I expect a phalanx of Boston’s finest to be present, with copies of the original score and a paddywagon.

Christopher Hyde is a writer and musician who lives in Pownal. He can be reached at:

classbeat@netscape.net

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.