Carl Little is known for his books that profile the work of Maine artists.

His latest subject, Joel Babb, began coming to Maine in 1971, but is just as well known for urban landscapes painted in places such as Boston and Rome as he is for scenes from the Maine woods.

Babb’s mastery of a landscape’s details, often garnered from the top of a skyscraper or during a helicopter ride, endows his paintings with the kind of realism that makes you feel as if you could walk right into the canvas.

His major works have included stunningly detailed panoramas from the top of the John Hancock Tower in Boston’s Back Bay as well as beautiful, true-to-life representations of the woods and streams near his Maine studio in East Sumner. Babb’s “subjects” in Maine have included the Schoodic Peninsula, Otter Cliffs, Eggemoggin Reach and Baxter State Park.

Babb has also painted physicians in Boston hospitals, and even tackled a “historical painting” of the first successful kidney transplant.

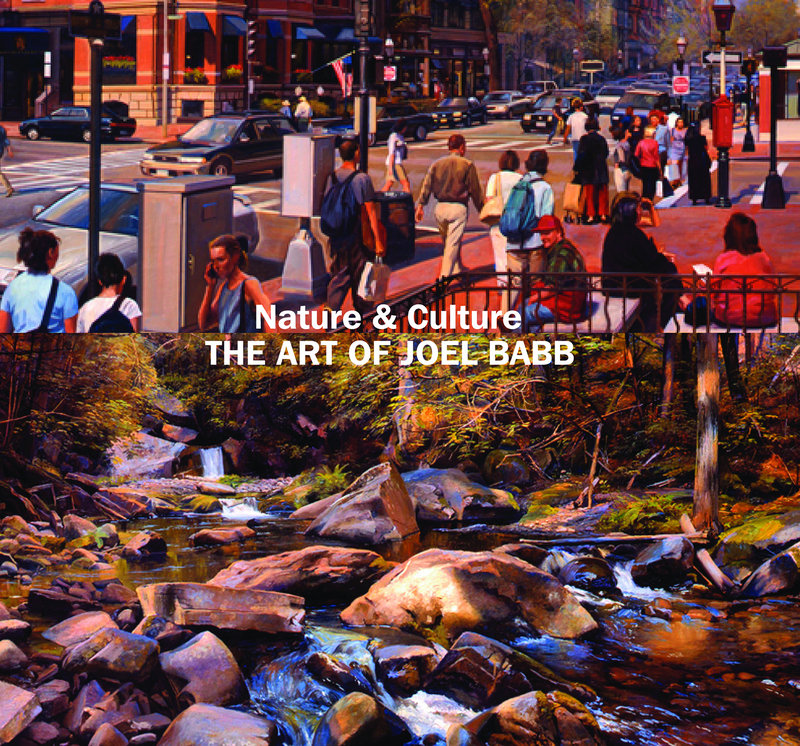

Little’s book, “Nature and Culture: The Art of Joel Babb” (University Press of New England, $50), includes words from the artist as well as short essays from Christopher Crosman, founding curator of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; scientist and author Bernd Heinrich; and novelist Anita Shreve.

Little, 58, lives in Somesville on Mount Desert Island. When he’s not hanging out with Maine artists, he works as the director of communications and marketing for the Maine Community Foundation. He recently chatted with the Maine Sunday Telegram about his latest book.

Q: What was it about Joel Babb’s body of work that intrigued you?

A: I think it’s the precision of his realism. It’s remarkable. I say in my little acknowledgements in the book that he really taught me how to see, and I mean that seriously. You look at a landscape and you pick out things, and there’s sort of a process to that, and he just takes that to the nth degree with the way he considers either a cityscape or one of those great deep interior Maine views.

There’s emotion there because he’s responding to the landscape, but there’s also this great, almost scientific response in the way that he treats it. He talks a lot about perspective and the optics of color. It’s really amazing to sit down and talk to him. He knows so much about his art.

Q: I took the book around to show my colleagues. Those Boston paintings are incredible.

A: I think we all respond to realism. Some people go, “Oh, it looks like a photograph,” but it’s so much more than that.

When you talk to Joel about a particular painting, there’s always a story behind it. There’s also always some license that he’s taken with the landscape. It’s not pure reproduction. It’s much more than that. So many circumstances come into play when he’s doing a particular painting — the mood, the season, his emotional wherewithal.

The one called “The Hounds of Spring,” which is one of his great Maine interior pieces: He had a site picked out for it, and then when the season changed it no longer worked, so he went elsewhere to find something similar. It’s a very careful process.

That said, he also has done a lot of commissions over the years, and one of the wonderful parts of working on this book was, I spent the better part of a day in Boston and Cambridge with Joel, and my son too, and we walked around and visited some of his commissions in the banks and at the Harvard Medical Library and other places. It was great, because in a few places, we were kind of taken into inner sanctums where the public doesn’t really get to go for some of these pieces.

Some of the commissions are wide open. The one in the lobby of the Charles Hotel, for example, everybody sees. But there were some other ones that were kind of hidden away. And Joel takes enormous pride in these paintings, some of which took him a long, long time to paint. They’re really remarkable.

That was a special treat, and I think the other real special treat for me in general when I’m writing about artists like this is having the opportunity to visit with them in their studios. He has a place over in East Sumner, Maine, which is really in the boonies, and has a beautiful studio there. To be able to spend time talking about his work surrounded by his work — surrounded by the studies and just the milieu of the artist, and the mahl stick that he uses for some of the perspective work and now the computer monitor that’s right next to the easel — you get a wonderful sense of the artist at work, and I’ve always considered that a privilege.

Q: While looking at the Boston paintings, I felt like they could be of historical importance someday, because it’s a snapshot of the culture and the way the city looked at a certain point in time. He seemed to think that too, mentioning in his notes that their “topographical accuracy” could make the works of historic value. How do you think future generations will look upon his work?

A: I think you bring up a great point. It’s absolutely true. The landscape’s changing all the time. Green spaces shift and move and appear and disappear. Whole neighborhoods, in some cases. These places change, and he has indeed captured them at a particular moment.

Q: I’m interested in the painting of the first kidney transplant because, as a science reporter, I interviewed both Dr. (Joseph) Murray and Ronald Herrick, the Maine man who donated his kidney to his brother in that operation. It says in the book that Babb worked from old photographs and the doctors’ memories. Can you talk a little bit about how he put that together?

A: It’s a great story, because it also has personal resonance. Joel himself had an operation when he was little. It was very serious, and it was heart-related. So when he was approached to do this commission of the first kidney transplant, he had a sort of personal stake in it. It was almost a way to overcome some of the early trauma.

It was a very complicated and complex commission because to recreate the scene, he not only worked from old photographs, but he also interviewed the doctors. And I think in some cases he got different stories and different perspectives because we all, in retrospect, remember things differently. And so he had to deal with that. He’s very proud of that painting. It’s in the medical library, and it’s opposite another great medical painting from American art history.

Q: Who are you writing about next?

A: I’m not sure. There are a couple of things in the works. But you know, living in Maine, this is like art central. There are just so many great artists. There are so many people I’d like to write about, books or whatever. There’s no end, and I’m discovering people all the time — new people; there are people from the past who reappear. It’s really wonderful. It keeps me very busy.

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.