James Nutter’s cellphone got a workout early Monday afternoon with incoming calls and text messages asking the same question: Had he heard the news? An active NBA player named Jason Collins revealed he was gay.

Nutter stopped what he was doing. If only Collins had gone public two years earlier when a 22-year-old college baseball player wrestled with his own sexual identity and was defeated. Nutter, the popular three-sport athlete from Kennebunk, was gay. Whom could he tell?

In the fall of 2011, Nutter planned his death. He had the pills to stop his heart, the whiskey to bolster his courage and the words to write the final note to his family, explaining why.

“Wow,” said Nutter, watching and listening to everyone from President Obama to Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant voice their support of Collins. “Wow. A great day. It’s pretty exciting. We have a face on a gay athlete. This is huge.”

Maybe people will no longer need to keep secret who they really are.

For three college baseball seasons, Nutter hid his sexual identity at the University of Southern Maine. No one knew he was pushing himself into a very dark place from which he saw no escape. He was a young gay man leading the double life of a straight teammate in the locker room. He had relationships with women but discovered he was more attracted to men. The deception was crushing him. If he came out, he feared the rejection of teammates who were like brothers. He feared being shunned.

Unlike Jason Collins, who had a productive career at Stanford University and became a respected role player in the NBA, Nutter could no longer find success at any level.

He left the baseball team and withdrew from USM. His family had learned he was gay and their love was unconditional. But Nutter was fighting bigger demons. He couldn’t finish the letter. He left his bedroom, went downstairs and cried to his parents for help.

What no one in the Nutter household could realize that night was how quickly the world outside was changing. Maine voters were about to approve gay marriage. Spurred by Nutter’s generation and the generation just ahead, gay lifestyles were becoming more acceptable. Even the military was coming to terms with the issue.

Martina Navratilova created a media and social storm when she revealed she was gay in 1981. She was one of the top tennis players in the world. More than 20 years later, the attention was muted when Sheryl Swoopes, a three-time Olympic gold medalist in women’s basketball, announced she was gay. She was in the middle of her career with the Houston Comets of the WNBA.

None of that helped James Nutter. While gay female athletes could step forward, gay male athletes didn’t feel that freedom. The locker room that might have been Nutter’s sanctuary had become his private hell.

When Ed Flaherty, the long-time and successful USM coach, checked the pulse of his team during Nutter’s career, he detected nothing amiss. Nutter was the son of one of Flaherty’s boyhood friends. He was one of the guys.

In fact, Nutter never felt more alone. He tried harder to be the straight man everyone thought he was. His grades plunged in 2011. Used as a relief pitcher, he was no longer effective in ball games. His confidence left and his self-esteem followed.

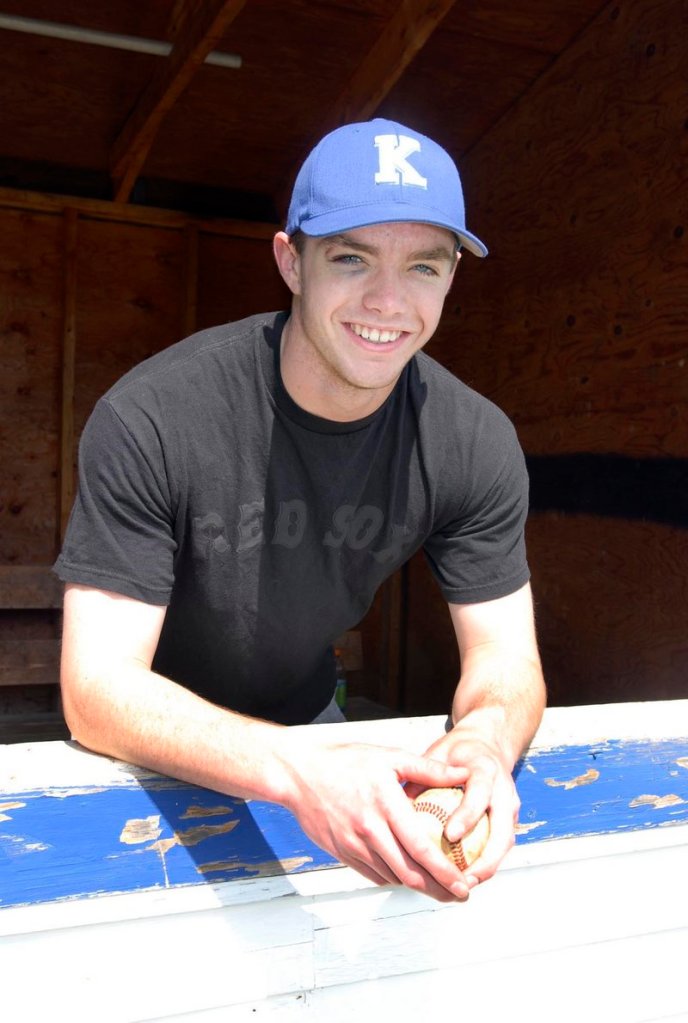

Flash forward to the Wednesday after the Boston Marathon bombings. Nutter was back on the USM campus for a photo shoot for this newspaper. It was only his second visit after a November story detailing the struggle with his sexuality appeared on an Internet website called Outsports.com. Cyd Zeigler Jr., the site’s co-founder, wrote a powerful narrative. In his reporting, Zeigler talked to Flaherty, Athletic Director Al Bean and a teammate or two for the story.

Nutter’s secret was out for months when he walked into the Costello Fieldhouse that morning. If he had apprehensions about seeing familiar faces, they vanished quickly. Wide smiles and happy-to-see-you hugs welcomed him. It was far from the reaction he once feared.

“I know,” said Nutter, marvelling at the affection. “If I had been braver, I would have told my teammates and not gone through so much pain.”

Today, Nutter cannot think of one teammate or friend or family member who turned their back on him when he came out.

Homophobic slurs were tossed around the USM locker room so casually when Nutter was there. He shared a four-bedroom suite at Upperclass Hall where many of the ballplayers lived on the Gorham campus. The locker room talk followed Nutter there. It wasn’t constant and probably couldn’t be called gay-bashing. It was a form of teasing or hard-edged kidding, but it wounded Nutter just the same.

He was too worried teammates were getting close to discovering his secret identity to understand they were simply joking.

USM is proactive in exposing its students to LGBT, or lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, issues. Bean, the longtime athletic director, is especially sensitive, organizing workshops for his coaching staffs and inviting speakers to talk to students about gay rights, which are really human rights.

None of that helped Nutter. Flaherty noticed the struggles. This was Bob Nutter’s son, after all. “I knew something was wrong, but I couldn’t find out what,” Flaherty said earlier this year. “I’d ask myself what was I missing. I talked to my captains.”

Flaherty had his own epiphany on gay athletes in a straight world more than 10 years ago. One of his players and an opponent got into a fight after a bang-bang play on the basepaths. The USM player was thrown out of the game.

Flaherty ran onto the field to confront of the umpire. Two fought, only one got tossed. Why my guy?

Because, said the umpire, your player called the other a (homophobic slur). So what? said Flaherty. Everybody uses that word.

Not in my games, said the ump. Flaherty never forgot. What’s more, he thought on it. If he heard the jokes and slurs, he’d call out the offenders, telling them he didn’t want to hear it. That same raucous kidding went on away from Flaherty’s hearing.

Nutter was a closed book. No one could read him. Maybe no one tried. Partly in denial, sometimes hating who he was, Nutter looked for help. Whom could he trust? Who would stand by him?

His father would, had he only known. “I wished we could have talked more,” said Bob Nutter, a star athlete himself some 45 years ago at Portland’s Deering High. “We never talked. Not about who he was. I will say this. This has brought us all (mother Katherine, older brother Rob) together so much closer. I’m sorry it had to happen this way.”

Sports Illustrated didn’t pick up James Nutter’s story as it did with Collins. Nutter was far off mass media’s radar. Nutter wasn’t an active pro in a major sport. He wasn’t a major college player. Outsports.com has a much smaller audience. Nutter was at ease talking with Zeigler. But seeing a once-secret part of his life in pixels on a computer screen was something else.

“I didn’t know how people would react,” said Nutter when we met at a downtown Kennebunk coffee shop a month after his story first appeared. “I felt like a man blindfolded, jumping off a cliff.”

He was free. Later in December, he went back to Kennebunk High to tell dozens of faculty members that the well-liked student and star athlete they once knew was gay. Copies of the Outsports.com story had been distributed to the staff but not everyone had read it.

Use me as a resource, as an ally, Nutter told them. He could support other gay students who didn’t know how to raise their hand and ask for help. Kennebunk High encourages its students to pledge to help others. The idea of a gay-straight alliance is more than words at this high school. After Nutter spoke briefly, the line formed to embrace him. It was emotional.

Nutter hasn’t become an activist in the typical sense. He doesn’t preach. He simply tells his story, knowing he might save a life or, at the least, save someone many days of hurt.

“James is effective. He’s honest,” said Patrick Burke, one of the founders of the You Can Play Project. “He’s taken an active part on our panel discussions. He has something to say and people listen.”

Burke is the son of Brian Burke, a former NHL player who rose to become general manager of several NHL teams, including the Anaheim Ducks. Patrick Burke is a scout for the Philadelphia Flyers, a law student in Boston and active in You Can Play. He is a straight man; his younger brother was not. Brendan Burke was killed in a car crash in 2010. He was 21, had been the manager of his college’s hockey team and suffered much as Nutter did in that locker room culture.

You Can Play’s mission is clear: Casual homophobia will not be tolerated in locker rooms. The NHL has thrown its support behind the project. A month ago, You Can Play was linked to rumors that it would support several gay athletes currently on major professional sports teams who were about to come out.

“It’s going to happen. We just don’t know when,” said Burke during a brief conversation. A week later, the Jason Collins story broke.

“That came as a complete surprise,” said Nutter. “I’m glad it did. Finally, we have a crack (in the dam of homophobia). The water is trickling out. Pretty soon that crack is going to be bigger. It’s all happening pretty quickly.”

While so many were transfixed by the death and capture of the Boston Marathon bombing suspects — Nutter was at a fundraiser for You Can Play elsewhere on Boylston Street when the bombs went off — he spoke the Friday after Patriots Day to about 500 students at Montclair Kimberly Academy in New Jersey, not far from Newark. It was Nutter’s first talk to an audience that large.

“He hit it out of the park,” said Dominique Gerard, the private school’s dean of student life. “He was completely awesome. Kids can spot insincerity right from the start. James spoke from the heart. None of it was rehearsed and the kids picked up on that.”

Plus, the recent events at Rutgers, New Jersey’s state university, had primed Nutter’s audience. The students and faculty were angry and horrified at the physical abuse and homophobic slurs men’s basketball coach Mike Rice used on his players in practice. Rice was fired.

Gerard saw Nutter’s story on Outsports.com five months ago and decided he had to come to New Jersey. Gerard mentioned a speaker’s fee and Nutter balked initially. He wasn’t doing this for money.

“I think he’s about to be discovered,” said Gerard. “He can earn a lot more than the pittance we were able to give him.”

Nutter has been busy. He was flown to San Francisco this winter for a conference. You Can Play uses him. Al Bean has asked Nutter to speak to the USM coaching staffs this summer. Other gay rights groups and advocates have lined up. A baseball player at MIT in Cambridge read Nutter’s story, called a meeting of his teammates and coaches in February and came out. Nutter, he told media outlets in Boston, was his inspiration.

“How do I feel when I hear that? Kind of weird, actually,” said Nutter. “But that’s why I’m talking, hoping to help someone.”

“There’s a huge difference in James,” said his father. “His confidence is strong. He’s much happier. The Washington Post called (Wednesday). The Huffington Post, too. They want to know what he has to say (about Jason Collins and gays in locker rooms). I never imagined my son talking like this.

“I do know this is bringing back all the memories. It’s too bad this didn’t happen sooner.”

Bob Nutter can’t forget he nearly lost a son who feared letting the world know who he really was.

James Nutter has work lined up with a catering company this summer. He intends to resume classes, this time at York County Community College. He’ll switch his major to human behavior. He may look into playing baseball again in the Twilight League.

A straight friend talked with Nutter recently about having a drink together. Maybe at a gay bar?

“He asked me if someone would try to hit on him. I said, ‘You’re a good-looking guy. It could happen.”‘

Nutter’s friend looked stricken. What should he do if that happened?

“Just tell them you’re straight. They’ll know they’re wasting their time.”

Nutter laughed. It felt good to live again.

Steve Solloway can be contacted at 791-6412 or at:

ssolloway@pressherald.com

Twitter: SteveSolloway

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.