NEW YORK – Bugs, the bane of Sunday afternoon picnics, are opening a new horizon for researchers who are mimicking some of their more extraordinary attributes in a wave of research that may save lives in the future.

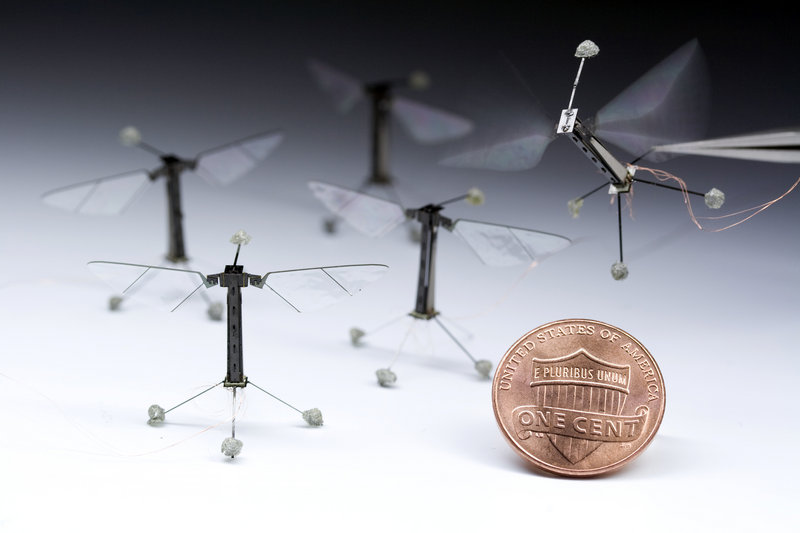

A digital camera with 200 lenses that mimics the compound eyes of ants may help improve endoscopes, the tiny cameras doctors use to explore the insides of patients. A tiny robot that borrows the aerial prowess of a house fly may one day help find injured victims buried in rubble after disasters.

The two technologies, announced separately in science journals last week, are the latest advances that use biological systems as models to design materials and machines. While copying nature has long been a staple of human innovation, recent technology advances that let scientists look more closely at insects, and stronger collaboration between engineers and biologists, have set off a wave of new discoveries.

“The walls that divided the life sciences and the physical sciences are sort of becoming transparent, so we’re trading ideas,” said Kevin Ma, a mechanical engineering graduate student at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., who helped design the robotic fly. “That also helps with the trend toward biologically inspired technologies, because of the cross- pollination of the fields.”

Harvard’s Office of Technology Development is already in the process of commercializing some of the underlying technologies, the university said in a statement.

The bug-eyed camera, about the size of half a grape, was reported last week in the journal Nature. It’s constructed of 200 interconnected rubbery lenses, which together allow a 160-degree field of view. The lenses, linked together in a sheet, can twist and stretch, allowing them to be formed into different shapes for different views, said John Rogers, a study author and a professor at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana.

In traditional photography, lenses can focus only on one distance, with a decrease in sharpness on either side of that point. In the compound eye, the depth of field is infinite, so nothing is out of focus, Rogers said in a telephone interview.

This may one day provide a boon to camera-guided surgeries, or making more-effective surveillance cameras, he said.

“It’s a gut interest on my own part, in insects and the eyes of dragonflies,” said Rogers, who also plans to explore the eyes of shrimp and lobsters. “Insects are well-engineered at the eye and the machinery for flight.”

There are a number of hurdles to get the design into commercial production, Rogers said. The next step will be to increase the number of lenses, which would allow for very high resolution.

The bug-eyed camera and the robotic fly reflect new technologies that have helped make studying nature easier, according to Sherry Ritter, a research and education specialist at Biomimicry 3.8, a Missoula, Mont.-based consulting firm.

“One reason we can learn so much more than we have in the past is because we’re looking at micro and nano scales,” Ritter said in a telephone interview. “We have really slow-motion video now that shows how wings move, and at the micro scale, we can see how they’re attached.”

Getting the robot into the air took more than a decade of work, Harvard’s Ma said in a telephone interview. Its creation, though, offers two immediate benefits, the researchers wrote: Biologists get a new model to study insect flight, and engineers are introduced to some non-traditional materials that may be used to construct other tiny machines.

Flies were particularly appealing as a model because they maneuver so deftly, as anyone who’s tried to swat one can attest, Ma said.

The robot flaps its wings using strips of ceramic that serve as muscles, expanding and contracting when an electric field is applied.

For joints, the robot has slim hinges of plastic, and a control system commands the motions in the flapping wings, according to the report yesterday in Science.

Fuel cells must be developed before the robots can fly independently, the researchers said in their report. They are also studying how to add a camera or sensors.

Ma said, practical applications are “a far way out,” but added “if we can imagine autonomous robots of this size, they could help search-and-rescue operations look for human survivors in hazardous environments.”

The two initiatives are hardly the first pieces of technology to borrow from nature.

Famously, Velcro Industries BV fasteners were invented by Swiss engineer George de Mestral in 1941 after he noticed burrs caught on his dog. The burrs had hundreds of microscopic hooks that fastened onto equally small loops in the dog’s fur.

Now, though, there’s new energy in the field, according to Ritter, at Biomimicry 3.8. “This whole bioinspired, biomimicry field is about collaborating with people you’d never have collaborated with in the past.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.