In 2000, Linda Greenlaw’s spry nonfiction book, “The Hungry Ocean: A Swordboat Captain’s Journey,” was chosen as one of 100 distinguished books that best revealed the history of Maine and the life of its people.

By including such a recent work along with proven classics including Sarah Orne Jewett’s “Country of the Pointed Firs” (1898) and E.B. White’s “Charlotte’s Web” (1953), the selection committee took a bold leap of confidence concerning “The Hungry Ocean’s” enduring merit.

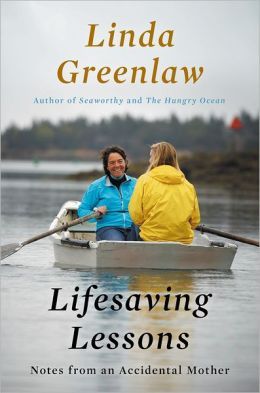

So far, that decision has reflected well on the committee and the work of a first-time author that enjoyed widespread popularity, and seems well on the way to becoming a commercial fishing classic. Better yet, Greenlaw has followed up with eight well-written and entertaining works of fiction and nonfiction, the latest being “Lifesaving Lessons: Notes from an Accidental Mother.”

As the title states quite plainly, this is the fisherman’s account of trying to become the legal guardian of a 15-year-old teen whose “uncle” has abused her. This may sound like quite a departure from the drama of swordfishing or even lobstering in the waters of Isle au Haut, but it is really the same good prose about Greenlaw’s life.

In this account, she has changed a few names for privacy reasons, but the story is blunt and reads true. Greenlaw knows how to get to the point, weave it through a colorful but real background, and report a story. Fans of her previous efforts will be pleased, and I think new readers will be fascinated.

Having mostly left the Grand Banks and deep-sea fishing for local waters, Greenlaw has settled on remote Isle au Haute, half of which is a park, the rest with a year-round population of 40. She is lobstering, seine-fishing (with unfortunate results) and writing, which leaves scant time for socializing. She has an occasional boyfriend in Vermont, but other than firm connections with her mother and sisters, her emotional life is clearly on the back burner.

One night, a teenage girl, Mariah, runs to a neighbor on the island, pursued by an intoxicated “uncle.” The family is shocked by what the man is saying and by what she tells them, and it soon becomes clear that “Uncle Ken” is no relative at all, but a sexual predator who obtained legal custody from Mariah’s birth mother in Tennessee.

Previously, both Mariah and Ken did not seem out of the ordinary, and like many of the locals, kept to themselves, though Mariah worked summers as Greenlaw’s assistant (sternman) on the lobster boat. All Linda knew was that Mariah was a capable worker.

The islanders closed ranks and went to the authorities. Because most everybody except Greenlaw had families, she was nudged into taking charge of the young woman.

As the accidental mother writes midway through the volume: “When our friends, family and neighbors congratulated us on achieving our new guardianship/ward status, Mariah’s response was ‘yeah, whatever.’ Although I was glad to hear something other than ‘lame,’ I couldn’t ignore the way two words from this kid could suck the life out of me.”

This proves to be a journal about personal growth. The author was no more prepared to be a parent at the outset than Mariah was ready to be parented. Greenlaw’s initial idea was to give this teen a place to live and get an education. The role of mother had never been high on her agenda. Indeed, much of the book concerns the role of the individual, the role of family and that of the community.

But this is collapsing a rather fine work into a few lines. Greenlaw’s story is about a struggle to make things right for both individuals, and assistance comes from a variety of surprising sources.

Above all, this is no saccharine attempt at self-canonization, but rather the amazing exclamation of how Greenlaw found Mariah, they endured, and then, sustained by family, friends and neighbors, got on with their lives.

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.