If Sauvignon Blanc is, for even the least wine-schooled, the most basic character in wine, Sauvignon Blanc from Sancerre — the region of France’s Loire Valley where most people believe the grape reaches its apogee — occupies similar cognitive space for self-professed oenophiles.

Every sophisticated wine drinker knows what Sancerre is, the way everyone knows how to scramble an egg. A fixed idea exists, gained through dull repetition and apathy. Actual experience and scrutiny having been long ago forsaken. Most people scramble eggs too fast on too high a flame, with the result compacted and monotonous, only faintly hinting at joy. A “truth” is established, only faintly echoing the truth.

The fact that standard Sancerre is beautiful wine, elegant and harmonious, expressing delicate balance between “mineral” (though more on this later) and “fruit” (ditto), makes the monotony of its default profile no less dull, no less inaccurate.

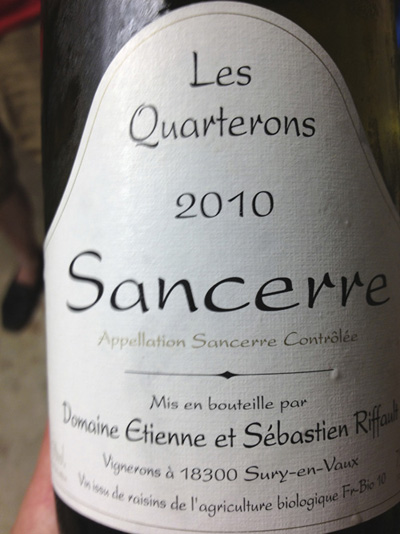

I’ve got the wine to prove it. The Sancerres of Domaine Etienne and Sebastien Riffault show that you may think you know what Sancerre “is,” but you don’t. You taste this Sancerre and every comfortable, agreed-upon cognate for Sauvignon Blanc, for the Loire, jumps into the dustbin.

Upon first smell, first taste, the reaction is, “This is amazing.” And then, “This can’t be Sancerre.” But you will persist in thinking this wine is the anomaly, that it is abnormal. The most delightfully troubling thing, though, given how traditionally Riffault works, is that his wines invert “the norm.” They taste the way wine tasted in Sancerre before certain changes were enacted to adjust to perceived market preferences.

Riffault told me it’s the old men of Sancerre who recognize his wines. The 1990s saw the start of widespread efforts to make Sancerre more “fruit forward,” to appeal to imagined “international tastes” and correct for so much improperly farmed (read: picked prematurely) grapes making Sancerre taste so acridly herbaceous. But there was always a small group of Sancerre producers (including Sebastien’s father, the Etienne in the domaine’s name) who knew the region’s birthright was mineral.

For this Riffault domaine, the standard practices of growing grapes organically and farming biodynamically are just the start. Much of Riffault’s plowing is done by horse. All fermentations take place with the natural yeasts that exist in the vineyards, and therefore are slow both to start and finish. Just as long hang-time on the vine leads to more thorough ripeness, long, relaxed fermentations lead to more complexity of flavor and an almost fibrous, knotty texture in the finished wine.

The wines even undergo malolactic fermentation, a rarity in Sancerre. But Riffault insists that conventional Sancerres don’t go through that transformation from tart apple-y acids to soft milky acids only because they receive so much sulfur. Riffault’s single-vineyard Sancerres (the Auksinis and Skeveldra wines are available in very small quantities in Maine, each for around $32) receive no sulfur at all, which along with lack of fining and filtering accounts for their cloudiness in the bottle. Les Quarterons 2010 ($26, Devenish), an assemblage of different vineyards, receives a scant 10 mg of sulfur at bottling (in Sancerre, 120-150 mg is customary) and a light filtration.

Perhaps the most influential factor in the intensity, suppleness, lushness and length of Riffault’s wines is the fact that he harvests grapes a full month later than most producers in the region, usually in mid-October. We taste this as magnanimously expressive fruit, bodacious and honeyed. But, do not interpret “honeyed” as implying sweetness, for this is vehemently dry wine.

In fact, it’s likely the Sancerre you know has had sugar added, to artificially introduce a sweetness that seems like fruit-ripeness as well as to raise alcohol levels and stage a performance of textural luxury. Riffault’s Sancerre comes by its weighty significance more honestly. The “fruit” is just intensity of flavor, more akin to the fattiness and earthiness known as umami than to boring ol’ berries.

And mineral! Riffault burst yet another of my Sancerre assumptions when he explained to me how what we consider “minerality,” a flinty impression of struck stones, is usually the direct result of sulfur added to wine. True minerality, he said, only expresses on the palate as salt and chalk. This is what all his wines have: thrilling pulses of saltiness and calcareous grip that come straight from the land that birthed them.

The mineral landscape of the wine is inhabited by all sorts of life forms: meringue, clafoutis, sun-baked straw, bees, strange flowers. Little in the wines is citric, nothing is green; all is amber and almandine, copper, soft yellows.

The name of “Riffault” is so common in the Loire it seems to me like a French version of “Smith,” and several fine Sancerres are made by others who share Etienne and Sebastien’s surname. My fear is that you will see this name listed in restaurants and think, “Oh, a Sancerre, made by a Riffault. I’m sure it’s good, but I’m going to choose something more interesting.” And maybe you will. But if you neglect this wine, you’ll not only miss out on a fantastic wine. You’ll have missed a great opportunity to get past a misapprehension about an entire place, grape and approach to life, a misapprehension always at risk of extending far beyond wine.

Joe Appel works at Rosemont Market. His blog is soulofwine.com, and he can be reached at soulofwine.appel@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.