KANSAS CITY, Mo. – Hey, YOLO, right? You only live once.

Despite all the comforts of Microsoft’s spell-checking angels, the digital generation will still have to appease the stubborn gatekeepers standing between them and future success who still expect the right use of “your” and “you’re.” And no “UR.”

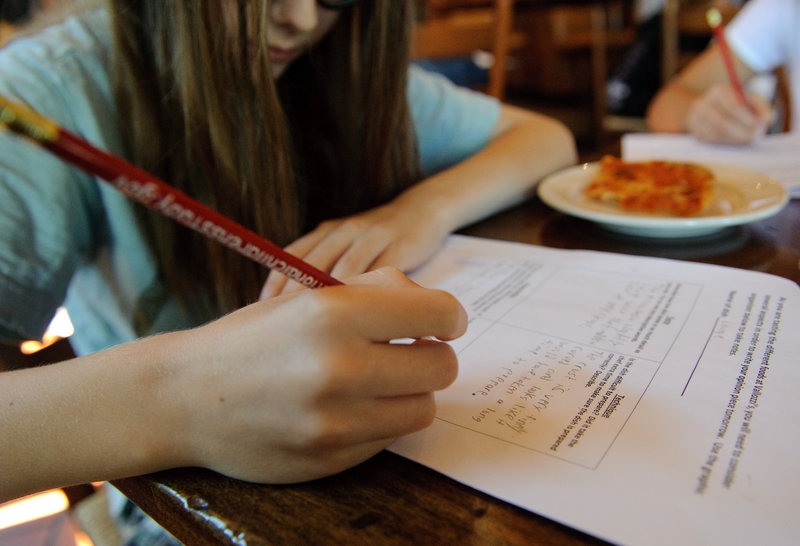

In their classrooms, new tests for the Common Core State Standards on language arts will demand more writing. Competitive college applications will keep requiring essays. And important first impressions in career opportunities will still suffer from careless spelling.

“There’s going to be a real reckoning,” said spelling education specialist Louisa Moats, if schools let slip the attention that teachers and students give to the structure of language. “There is no reward for ignorance.”

It is a confusing time, say members of the digital generation.

“I think I’ll hire a scribe,” said 20-year-old Cole Payne, a student at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

He was kidding, mostly. But he and others realize they are racing along a narrow balance, with the lure of slang and shortcuts pulling in one direction and the demand for good English still pulling in the other.

Call it a new strain of an old disease.

STUDENTS WRITING, BUT SKILLS SLIP

Slang has been around for centuries, and reading and writing have long been under siege by television and video games.

Four years ago, the National Endowment for the Arts bemoaned a 14 percent decline over 20 years in the percentage of 13-year-olds who are daily readers. Less than one-third regularly picked up books.

Recovering the lost reading and writing skills is complicated in the new age.

Today’s rapid writers are perilously dependent on “the squiggly lines,” said Rebecca Kramer, a 21-year-old University of Missouri-Kansas City student, referring to Microsoft Word’s red and green lines that are supposed to warn of possible spelling or grammar errors.

They like to think they can turn on their good, formal language skills when necessary, said 20-year-old UM-KC student John Kaleekal.

But he senses some doubt.

“I wonder if we feel we can handle it,” he said, “but in reality, an English professor would tell (us) things we can improve on.”

Here is the undeniable upside to all of this digital communication, whether on phones or laptops, in social networks or blogs or classroom projects: Students are writing.

“In the past, it was trouble getting students to even write,” said Kourtney Michael, a journalism and English teacher at Raytown South High School. “But now they are learning that communication is power. They have an audience. They are learning that every word has meaning and there is power in that.”

A survey of teachers by the Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project published this summer found that eight of 10 teachers agreed that digital technologies were spurring creativity, collaboration and personal expression. Students are more invested and engaged in the writing process, they agreed.

But seven of 10 also agreed that the technologies made students more likely to take shortcuts and put less effort into their writing. Careless slang and fractured spelling, they feared, are creeping into formal settings.

It can be a fight, Michael said, for the teacher circulating among her writing students. She must urge them to vet their online sources, tend to grammar and check their spelling. “Sometimes they don’t even use periods,” she said.

ENGLISH A CHALLENGING LANGUAGE

When it comes to shortcuts — particularly with spelling — no language asks for it like English.

All those texters and bloggers who’ve had “enuff” of conventional spelling in some way are striking back at a history of English spelling that is almost comical.

Literacy researchers Masha Bell and Edward Rondthaler, among others, have retraced the language’s unique path to confusion.

From its Anglo-Saxon beginnings, English spelling initially followed the path of most languages: Scribes wrote down letters to represent the sounds coming out of people’s mouths. But complications arose with the first print shops in London in the 1400s.

Typesetters came from Belgium and Holland, which had already developed printing, and inevitably inserted errors into a less-familiar language. Furthermore, the historians say, they were paid by the line, so it was to their advantage, say, to change “program” into “programme.”

In the 1500s and 1600s, English scholars considered Greek and Latin superior to their own crusty Germanic roots. “Debt” was spelled with a “b” because it would at least look like it derived from the Latin “debitus.”

Dictionaries followed in the 1700s, the most authoritative being Samuel Johnson’s of 1755. Johnson, when affixing spellings, likewise valued the etymological roots of words over their sounds.

In America, Noah Webster’s dictionary in the early 1800s sided with forces trying to drive out at least some of the unnecessary letters, so we have “honor” instead of the British “honour.”

But overall, the English writing world has been mostly locked into its out-of-sync spelling system.

Most major languages have international regulatory boards that adapt official spellings to match evolving pronunciations — but not English.

Numerous attempts over the centuries by organizations bent on simplifying English have failed, despite being backed by names as prominent as Theodore Roosevelt, Andrew Carnegie and Mark Twain.

So anyone who wants to be at least a moderately competent speller of English, writes Bell, has to memorize at least 3,700 words with unpredictable spelling.

Despite all their mashing of words when they send texts, students said, most of them know better than to abandon good English.

The fear among many teachers and professors, however, is that the necessary discipline in writing may be suffering too much.

“Kids know how to code-switch,” said UM-KC Associate Professor sj Miller. “They know when (text-speak) isn’t appropriate.”

GUIDING THOSE RAPID WRITERS

But he said he sees some students getting lazier. Many rely on their computer programs to prompt them about grammar errors, and they are making changes without knowing why.

“It’s not the end of grammar as we know it,” Miller said. “But there is a shift. We can stabilize it if teachers can be savvy.”

Moats’ concern is that teachers are vulnerable to the same lack of foundational knowledge.

Moats, a consultant with Sopris Learning, helped draft the reading skills section of the Common Core State Standards now adopted by most of the nation. It troubles her that the foundational skills of language get less attention in the new standards than other skills along the path toward strong reading comprehension and writing.

People mistake spelling as an exercise of rote memorization, she said. Knowing the roots of words and why they are spelled the way they are helps students learn to decode more words otherwise unfamiliar to them. It helps build comprehension.

She is not optimistic.

Too much of the writing done by youth becomes “an unfortunate diversion from the real world” that they will be competing in, Moats said.

“The ease of (digital) communication belies the mental effort it takes to write well — the intellectual stamina and energy — to express ideas clearly and in an organized way,” she said. “I don’t think it is making us any smarter. It’s an illusion that we are smarter.”

There is no question that this is “a very exciting and auspicious time,” Miller said. A new school year means teachers will be redoubling their efforts to guide this generation of rapid writers. And they will have to be quick to run with them wherever technology leads.

“Where it is going to go next,” Miller said, “is the inscrutable mystery.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.