WASHINGTON – Call it a hidden ally: The right germs just might be able to help fight fat.

Different kinds of bacteria that live inside the gut can help spur obesity or protect against it, say scientists at Washington University in St. Louis who transplanted intestinal germs from fat or lean people into mice and watched the rodents change.

And what they ate determined whether the good germs could move in and do their job.

Thursday’s report raises the possibility of one day turning gut bacteria into personalized fat-fighting therapies, and it may help explain why some people have a harder time losing weight than others do.

“It’s an important player,” said Dr. David Relman of Stanford University, who also studies how gut bacteria influence health but wasn’t involved in the new research. “This paper says that diet and microbes are necessary companions in all of this. They literally and figuratively feed each other.”

The research was reported in the journal Science.

We all develop with an essentially sterile digestive tract. Bacteria rapidly move in starting at birth — bugs that we pick up from mom and dad, the environment, first foods. Ultimately, the intestine teems with hundreds of species, populations that differ in people with varying health.

Overweight people harbor different types and amounts of gut bacteria than lean people, for example. The gut bacteria we pick up as children can stick with us for decades, although their makeup changes when people lose weight, previous studies have shown.

Clearly, what you eat and how much you move are key to how much you weigh. But are those bacterial differences a contributing cause of obesity, rather than simply the result of it? If so, which bugs are to blame, and might it be possible to switch out the bad actors?

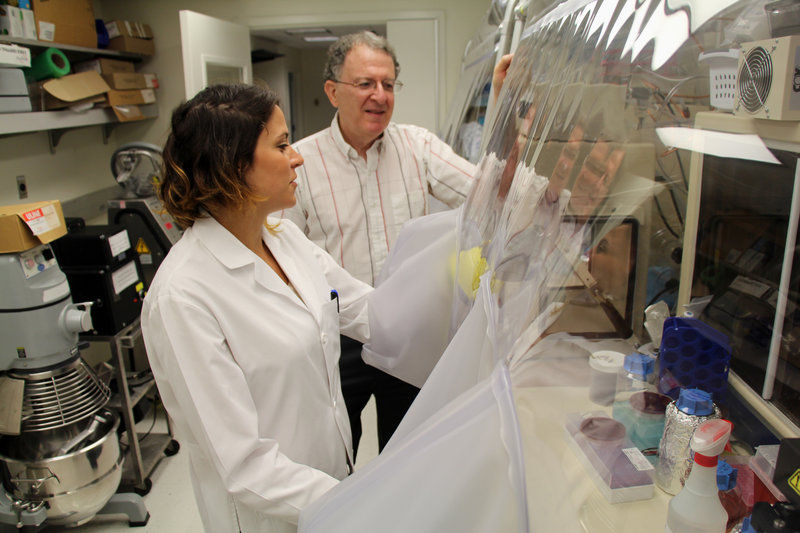

To start finding out, Washington University graduate student Vanessa Ridaura took gut bacteria from eight people — four pairs of twins that each included one obese sibling and one lean sibling. One pair of twins was identical, ruling out an inherited explanation for their different weights. Using twins also guaranteed similar childhood environments and diets.

She transplanted the human microbes into the intestines of young mice that had been raised germ-free.

The mice who received gut bacteria from the obese people gained more weight — and experienced unhealthy metabolic changes — even though they didn’t eat more than the mice who received germs from the lean twins, said study senior author Dr. Jeffrey Gordon, director of Washington University’s Center of Genome Sciences and Systems Biology.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.