World markets were in a tailspin, and thousands of Americans were losing their homes to foreclosure. Unemployment was creeping toward 10 percent as stock markets plunged.

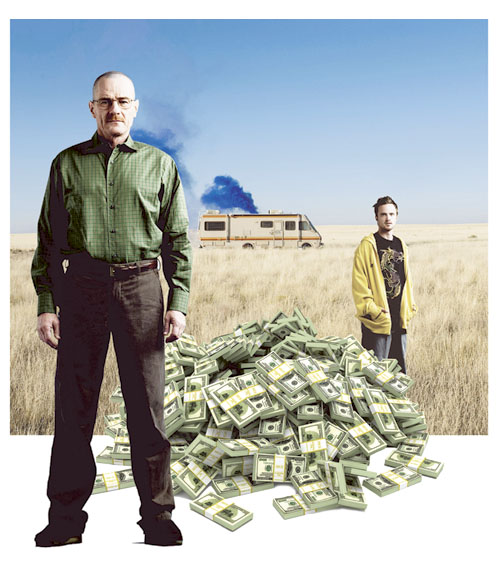

So it’s no wonder that viewers instantly connected with the meek, underemployed New Mexico chemistry teacher, played by an intense Bryan Cranston, whose terminal cancer becomes a wake-up call to find a new source of revenue to secure his family’s future.

First quietly, then in fits of calculated rage, White lashed out at the institutions and people responsible for his neutered life, determined to exact revenge on his past decisions by building himself into someone new. Street justice, it seemed, had a new mascot, and unlike the blindfolded, scale-holding female memorial to American due process, the new anti-hero wore a black hat, and his eyes were wide open.

“I am awake,” said White, during the first season, after he discovered his proclivity for cooking high-quality methamphetamine. Through five seasons, viewers have marveled at the brave, dramatic and darkly comedic series and the ability of its fictional characters to trigger questions about morality, politics and right and wrong.

Granted, cooking purified methamphetamine for profit is a novel, if not outlandish, way to discover one’s true empowerment. Yet at his core, is the felonious anti-hero Walter White and the world he inhabits so far from the realities of modern America?

How is White’s struggle in a hypercompetitive, high-stakes marketplace different from the sort of maneuvering and conniving that has become common to America’s wealthiest elite? What’s the difference between running the front of the A1A carwash and the countless millionaires whose wealth is squirreled away in secret offshore bank accounts?

And perhaps more important, do the values that made Walter White a success offer any wider redemptive value for the rest of us who are left toiling away at the bottom?

According to one University of Southern Maine professor, much about White’s fictitious world directly applies to our modern economy and politics, and the results, taken to the dramatic extremes that make the show such a nerve-wracking pleasure to watch, can be quite frightening.

“What’s happening this season is everything is coming home to roost,” said Professor David Pierson, who is editor of “Breaking Bad: Critical Essays on the Contexts, Politics, Style, and Reception of the Television Series,” a volume of scholarly essays due out in November from Lexington Books.

“All the rational choices (White) made, which includes killing and all sorts of horrible things, now he’s sort of paying the price, and it’s going to affect his family,” Pierson said. “It’s going to affect everybody around him.”

Pierson argues that White is an example of neoliberal theory run amok, where markets — both legal and illegal — are left to regulate themselves, and rational, self-interested decisions reign supreme.

Neoliberalism, generally defined by Pierson and others, is the belief that free markets should be the organizing force for nearly all aspects of life, from the economy and governance to social organizations and personal decisions.

Pierson writes that the ideology crossed over from theory to practice largely during the administration of Ronald Reagan, and has since spread across the world as a dominant economic theory. Politically speaking, neoliberal ideals emphasize private enterprise, consumer choice and personal responsibility — themes that should sound familiar to spectators of many policy tussles in Washington, D.C.

Conversely, traditional liberalism is embodied by the 20th-century programs of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. In this view, it is the role of government to promote the common good, often actively intervening in the lives of individuals through public education and support programs for the poor and underclass.

Pierson said the real-life American Southwest is a particularly apt setting for his theory, with its low taxes, weak or nonexistent labor unions, plentiful retirees, high rates of immigration, limited access to middle-class jobs and a wide disparity between rich and poor.

It is not too far-fetched that in a few dozen years, social historians will look back at the fictional drug market of “Breaking Bad” and see it as an analog of politics of the early 21st century: Winners take all, fortunes shift rapidly and government intrusion (in the form of the Drug Enforcement Administration) represents an integral threat to the way business is done.

Those rules sound alarmingly close to the vision proffered by a recent generation of American politicians, who call for eliminating parts of the federal government and allowing businesses to regulate themselves, and call for lowered taxes on the wealthy so that entrepreneurs are not penalized for their hard work.

While we’re left to watch, impatiently, for answers from our representatives in Washington D.C., we can always count on Walter White, whose American Dream is about to come to a crashing conclusion.

Matt Byrne can be contacted at 791-6303 or at:

mbyrne@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.