Maine College of Art alum Ahmed Alsoudani is in the thick of a meteoric art-star-in-the-making moment, so it was a coup for PMA director Mark Bessire to bring his first major museum show to Portland.

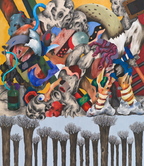

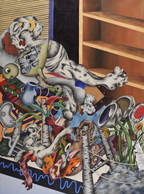

“Ahmed Alsoudani: Redacted” features 20 recent works by the Iraqi-born artist. The works are large paintings in acrylic and charcoal brimming over with signs of grisly violence. Such grotesque imagery – severed limbs, guts, pop-out eyes, etc., – immediately warns you to expect the worst. Alsoudani’s biography (repeated ad nauseam in the marketing of his work) also sets you up for an experience of the horrors of war.

I generally take with a grain of salt what people selling the art say (artists, of course, top that list). But, having reached my own conclusions after visiting “Redacted” three times, I eagerly attended a public conversation between Alsoudani and Bessire sponsored by the Leonard and Merle Nelson Social Justice Fund.

Considering the sponsor, it was surprising that Alsoudani, whose family owned a factory, spoke of a “pretty normal” childhood and a life that was “no different” when he left Iraq for Syria. Yet the marketing wall copy says that Alsoudani, who was born in 1975, “experienced the traumas of the Iran-Iraq war… the invasion of Kuwait… the Gulf War… and crippling UN sanctions….”

While it might sound like I am taking this in a negative direction (and it will get worse in a minute), I want to be clear that Alsoudani’s performance completely reinforced my settled take on his work – which I came to truly enjoy during my second visit.

Despite the fact he is the first to say it, Alsoudani is good.

Again, the first impression is entering a realm of slaughterhouse horror. Walking through quickly only reinforces this effect. Yet “Redacted” is the best looking show I have ever seen in the PMA’s handsomest space – the soaring and gloriously skylighted third floor gallery.

This aesthetic moment matters because it opens the door to leaving the artist’s biography behind and looking at “Redacted” as an art installation.

We read repeatedly about Alsoudani’s escaping Iraq; coming to America; studying at MECA; getting an MFA from Yale; selling out his first NYC gallery show while still a student; showing at mega galleries in NYC, Berlin and Paris; and even representing the U.S. at the Venice Bienniale. It’s a good story and Alsoudani – in his trademark fedora – sells it well.

I assumed Alsoudani’s work was geared towards empathy with victims of totalitarianism and war, but the more I looked, the more the work appeared engaged with art history. I also assumed Alsoudani reached out to great painters because he could empathize with their experiences of war and horror. But the more I saw in Alsoudani’s work of Grosz, Bacon, Beckmann, Goya, Bosch, Bellmer, Picasso, Kollwitz, Dix, Hoch, Dali, early Pollock, DeKooning and Guston, the more it became apparent that Alsoudani’s work is not about war or victims; it’s about painting.

While the audience at the talk was probably expecting to hear about lost friends and relatives, the glib Alsoudani was saying things like “I’m really good,” “I am a little bit cocky – I know I am going to be around for many years to come,” and “I give myself credit: I steal.”

The “stealing” point came in the context of a comment commonly attributed to Picasso: “Good artists borrow, great artists steal.”

In the ensuing discussion about art history, Alsoudani said, “The history of painting is a like a mall for me. I just go shopping and grab everything.”

When you combine this attitude with Alsoudani’s insistence on avoiding specific scenes or subjects because he is “building an iconography for many years of painting,” it becomes clear that he isn’t identifying with the little boy blown up by a land mine or the folks oppressed by the dictators. Rather, he is identifying with Picasso, Francis Bacon and other painters who – like himself – are “great.”

Alsoudani’s work is art historical pastiche. He can paint. He can draw. And he has a great eye for quietly incorporating his references. For example, Dali’s ants crawl over a severed limb, and we can’t miss his empty clock face. Once I stopped looking for un-ironic depth in the vocabulary of modernist paintings about war, trauma and the tumultuous subconscious, I came to truly enjoy Alsoudani’s works (but then I can parse art historical references for hours longer than most people would ever want to).

Alsoudani interestingly noted that he often considers his works “finished” when he doesn’t paint on them for a couple of weeks. In other words, they aren’t about some articulated symbolic project – they are defined by the hermetic terms of painting.

Alsoudani’s paintings look like Grosz, Picabia or early Pollock if they were painted by Bacon, and higher praise I cannot imagine. Their necrotic vocabulary is decidedly hip at a time when zombies are all the rage – from television’s “The Walking Dead” and Manga graphic novels to the annual Zombie Kickball event in Portland. This feel for pop culture ephemera ties Alsoudani to the logic of Pop Art with its eye (disembodied and googly) on red carpet stars no less than the desensitizing effects of repetition.

The reviews of “Redacted” have been mixed because the works don’t stand up to the brutality they initially purport to address. However, these works are not about the horror of war but the culture of painting – that great mall where it seems we can always find Ahmed Alsoudani.

Talk sponsor Merle Nelson asked me: “But could you live with it?”

Yes, I say: Absolutely. After all, these works long for museum walls – not war-torn streets – and they have found them.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at: dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.