If Wally Lamb’s last full-length novel – the ambitious and breathtaking “The Hour I First Believed” – is about hope, then his new book is about courage. “(T)hat’s what it takes, doesn’t it? No matter which way our lives turn out,” says one character in “We Are Water,” musing on how unexpected events can shift what we thought of as solid ground beneath our feet.

We need courage to face the past, courage to step into the future. Life is dangerous. Great white sharks are congregating off the beaches of Cape Cod in “We Are Water,” but they aren’t the only predators to fear.

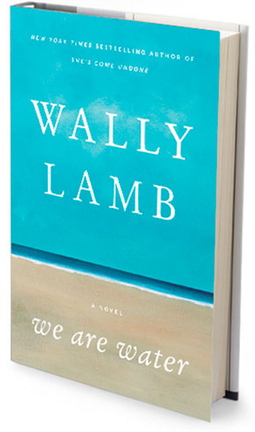

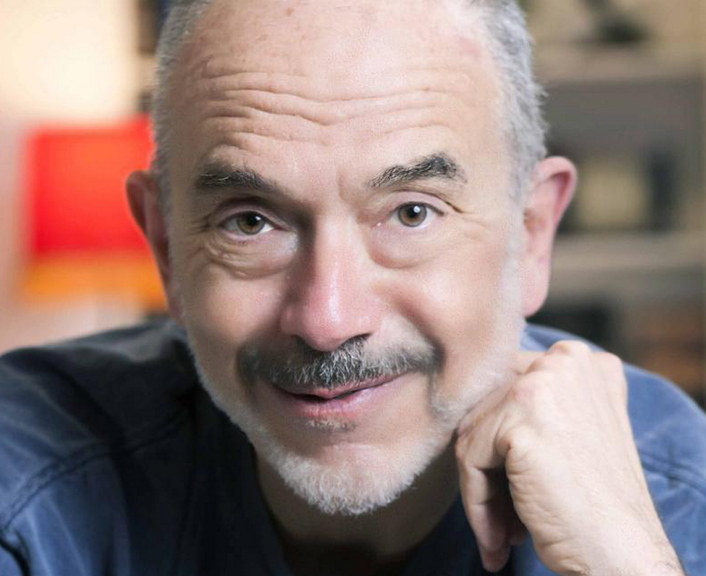

The Connecticut family at the heart of “We Are Water” is beset by dark secrets, upheaval and tragedy (like Lamb’s other books, the title was inspired by music, in this case an obscure work by singer/songwriter Patty Griffin). Everyone in Lamb’s novels is familiar with suffering; he’s also the author of “I Know This Much Is True” and “She’s Come Undone,” both Oprah book club picks, both unsparing in their exploration of life’s difficulties. But true to his talents, Lamb finds a way to incorporate in other diverse elements into “We Are Water” – a natural disaster, racial injustice, American life during the Obama years, even a bit of a ghost story – to add heft and depth to this painfully honest, character-driven family drama.

Lamb hones in on the Ohs at a momentous time. Parents Annie (an artist) and Orion (a psychologist) are freshly divorced. Annie’s success constructing shadow boxes launched her into the art world and lured her to glamorous Manhattan, where she fell in love with her dealer Viveca. In the wake of Connecticut’s new laws legalizing gay marriage, Annie and Viveca are preparing for a lavish wedding in Three Rivers, Conn., where Annie and Orion raised their family, which draws mixed responses from the rest of the Ohs.

Battered by a series of bad decisions and self-destructive behavior, Orion is still trying to find his footing. He has been invited to the ceremony but doesn’t really want to be there and is taking a month to collect himself, somewhat bitterly, at Viveca’s Cape Cod home.

The adult Oh children – twins Ariane and Andrew and their younger sister Marissa – view their mother’s coming nuptials from different perspectives. Ariane, who works in a soup kitchen in Berkeley, was angry at first on her father’s behalf, but now her insecurities have taken over; she just wants Viveca to approve of her. Marissa, a free-spirited, hopeful actress, takes the wedding in stride.

Struggling, though, is Andrew, who enlisted in the military after 9/11. Stationed in Texas and engaged to the predictably privileged/religious/virginal Casey-Lee, he has strayed from the beliefs of his liberal parents and is resisting his mother’s invitation. “(M)e and Casey don’t. … we feel that marriage should just be between a man and a woman. Whether, you know, it’s legal or not,” he tells Dr. Laura Schlessinger on her radio show. “Plus, I don’t know. I just think that going would be disloyal to my dad.”

But though he’ll also parrot the Adam and Steve joke popular with foes of gay marriage, Lamb never uses Andrew to poke fun at Texas conservatives (Casey-Lee flirts a bit with caricature, though Lamb is quick to point out she’s not wholly shallow). Andrew is thoughtful, and he’s grateful that finding faith has brought him peace of mind he never had before. His troubled past stems from a tumultuous relationship with his mother: The rage that fuels Annie’s art was often turned on Andrew (though not his sisters), a secret all three Oh children have diligently kept from their father. But as the day of the wedding draws near, so does the moment of revelation.

Lamb allows each of the Ohs to weigh in on the past and present, and their voices are distinct and true. He also incorporates the stories of outsider artist Josephus Jones, a black man who lived on the Three Hills property and died mysteriously after befriending a white girl, and a real-life flood that destroyed downtown Norwich (where Lamb grew up; Three Rivers is his fictional stand-in). Annie’s mother and baby sister perished in the flood, which changed the course of her life, all damage emanating from those terrible moments trying to outrun the raging water.

Other characters drift through the book, most notably a pedophile whom Lamb renders with chilling precision. “I’m not a monster. Hey, I’ve got my flaws. Plenty of them. But I’m more than just a name on the sex offender registry,” he says, adding with unsettling accuracy, “‘Predator,’ ‘pedophile,’ ‘child molester’: yeah, you could call me any of those things. But don’t forget ‘victim’ because that was what came first.”

Floods, predators, bigotry, abuse, murder: So much evil, so many secrets lingering on, maybe even into the next generation. Lamb adds scale to the malaise: Annie’s growing ambivalence toward her wedding takes on the tone of our growing national disillusionment. If we have survived the worst, what do we do when things still feel bad? She remembers the classic posters of Rosie the Riveter, marked with the slogan “We can do it!” and wonders when she – when we – lost hope.

“Obama’s campaign motto last year was a variation on that,” she muses. “‘Yes, we can!’ . … It’s turned out that Obama isn’t a superhero after all. Maybe that’s the legacy of those fallen towers, all those lost lives, our national feeling of futility. No, we can’t do it. It is what it is.”

But in the end, Lamb, for all his attention to serious matters, isn’t a pessimist. “We Are Water” ends on a hopeful note, maybe not with a perfectly happy ending but one that makes sense. “I think of something I read recently, I forget where, A life I didn’t choose chose me,” says Orion. We don’t entirely control our fates, Lamb tells us. But resilient, we still flow onward.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.