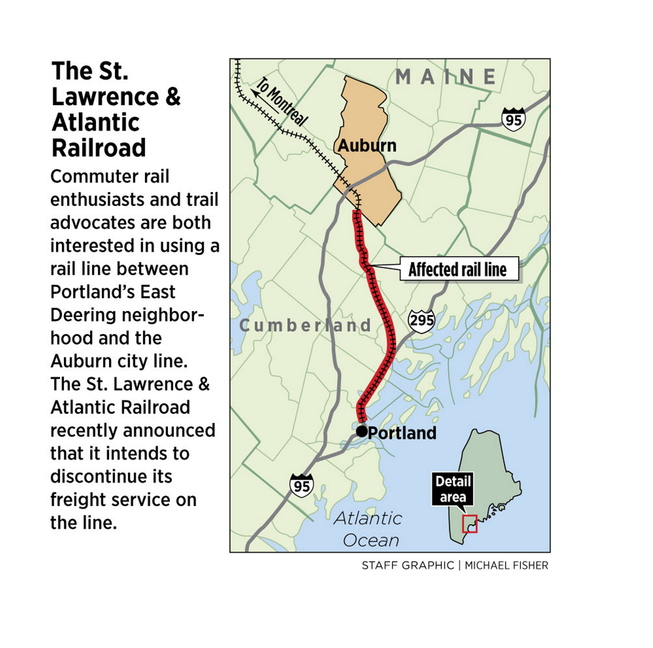

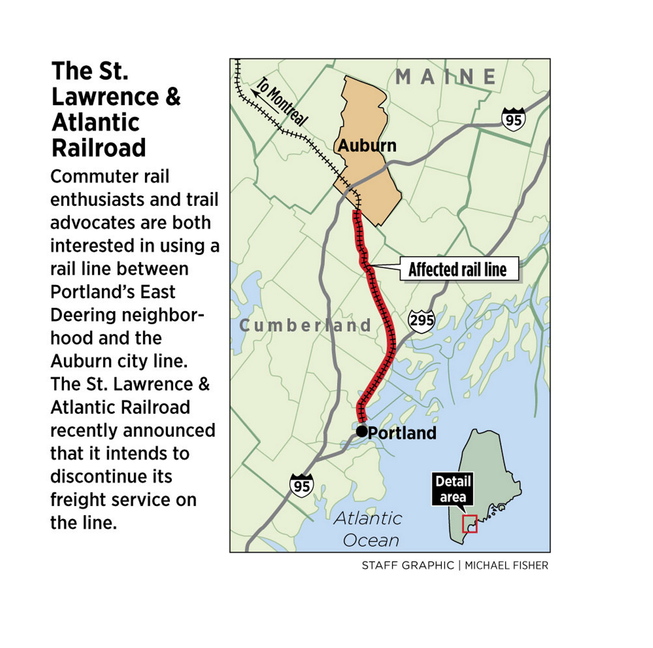

Recent news that freight trains could cease running on a section of railroad between Portland and Auburn has sparked speculation about the future of the 30-mile corridor.

While some see the demise of freight service as an opportunity to push forward on plans for commuter rail service, others envision a paved recreational trail that links Portland with its northern suburbs.

The conflict emerged earlier this month when the St. Lawrence & Atlantic Railroad filed a petition with the federal Surface Transportation Board seeking permission to discontinue freight service on the section of the line between Portland’s East Deering neighborhood and the Auburn city line.

Railroad president Mario Brault said the railroad is losing money on the line because it must maintain the tracks and crossing gates to serve just one customer in Portland, the Burnham & Morrill Co., makers of B&M Baked Beans.

The federal government is scheduled to make a decision on the request before March. But people are already discussing the line’s future without freight.

The state owns the right of way, having purchased it from the railroad for $6.8 million in two transactions, in 2006 and 2009.

The absence of freight trains on the line would make it easier to establish commuter train service because it would reduce potential scheduling conflicts and the number of parties that would be involved in negotiations, say supporters of passenger rail.

Meanwhile, from the point of view of trail supporters, the lack of freight service would make the corridor safer and more appealing for recreational use.

News of the railroad’s efforts to end freight service created excitement last week among trail supporters attending a public round-table discussion in Yarmouth about how area towns could work together to create a regional trail system from North Yarmouth to Falmouth.

“It helped light a fire under people,” said Mike Lydon, a consultant hired by the Portland Area Comprehensive Transportation System to help the towns plan for trails from a regional perspective.

He said a trail could share the same right of way as a commuter rail service.

“We wouldn’t want to preclude one or the other from happening,” he said. “We know they can happen together.”

Many people along the corridor would like to bicycle to Portland but are afraid of getting hit by a car on Route 1, said Dan Ostrye, chairman of the bicycle and pedestrian committee in Yarmouth.

A trail next to the railway would be a “huge benefit” because it would make commuting by bicycle safer and more appealing, he said.

But talk of a trail makes the advocates of commuter trains nervous because they worry it could complicate their efforts.

“We need businesses and jobs in Maine. The highest and best use in this corridor is moving thousands of people,” said Tony Donovan, a Portland commercial real estate broker who leads the Maine Rail Transit Coalition.

Members of the coalition view commuter rail service as an economic development tool because they believe it will raise property values and lure investment to the communities it serves. Unlike Amtrak’s Downeaster intercity service, which uses locomotives to pull cars, the coalition proposes using lighter and more efficient self-propelled cars, such as Swiss-made cars used by the transit authority in Austin, Texas.

The service would begin in Auburn and run to India Street in Portland. Replacing the tracks and building new bridges across Back Cove and the Royal River in Yarmouth, buying three rail cars and building new station platforms would cost an estimated $138 million. The group believes private investors would provide $20 million to pay for the platforms, stations and train equipment, and that a $30 million state transportation bond would leverage enough federal dollars to pay for the rest of the project.

A 2011 Maine Department of Transportation study, however, concluded that the service would not attract enough riders to be considered feasible for federal funding for engineering and design work.

The proposal has some support in the Legislature, which last session passed a resolution directing the Department of Transportation to seek funding for the design and engineering work. Donovan said the 2011 study is flawed, and his group has completed its own study that shows the project would be feasible for federal funding due to new federal rules that take into account a project’s economic and environmental benefits.

The group’s plan calls for 22 round trips a day and assumes there would be an average of 35 riders per trip paying an average fare of $8.

If freight trains or passenger trains don’t use the corridor, the unused tracks may remain for some time.

Unless the Legislature passes a law, replacing the tracks with a trail is not an option because the state purchased the right of way to preserve the railway, said Nate Moulton, director of the state’s industrial rail access program.

The idea of building a trail alongside the tracks may prove difficult because the corridor is too narrow.

It takes a lot of space to make room for trails and a railway. Design guidelines call for a minimum 10½-foot separation from the center of the tracks to a fence separating the trail, with greater setbacks when trains are faster and run more frequently.

For the most part, the right of way isn’t wide enough for both trains and bicycles, according to Carl Eppich, a senior transportation planner with PACTS.

“It’s a rail corridor and should remain a rail corridor,” he said.

The one exception is in Yarmouth, where the right of way appears to be wide enough for both tracks and a trail, Eppich said.

Tom Bell can be contacted at 791-6369 or at:

tbell@pressherald.com

Twitter: TomBellPortland

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.