Spurred by the release of the Coen Brothers’ “Inside Llewyn Davis,” a few weeks ago, I devoted this column to examining the difficulty in trying to depict a musical genius in a movie. Eventually, not being a musical genius, I resigned with a shrug, concluding that a great piece of music comes from innate talent, individual history, and that elusive stuff I simply will never understand.

But can musical greatness arise from a place?

That’s the argument put forth by the new musical documentary “Muscle Shoals,” which screens Friday at SPACE Gallery (www.space538.org), a beguilingly entertaining history of the tiny, titular Alabama town that is the unlikely birthplace of a truly startling array of classic popular music. Focusing on the hardscrabble life story of legendary producer Rick Hall, Greg Camalier’s film, apart from providing an intriguing and surprising history behind some of your favorite songs and artists, also posits that there’s something ineffably inspirational about Muscle Shoals itself which made those songs what they are. An alchemy of place, and history, and the ever-murmuring Tennessee River running beside the deep, dark Alabama earth which seeped into the music made there, and the musicians who made it.

Unfortunately, that theme of the film remains as elusive. I’m all for appreciating the unknowability of the creative process, but, even coming from the mouths of musical legends like Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, Jimmy Cliff, Percy Sledge, Bono, Gregg Allman and Etta James, the idea that the town of Muscle Shoals can impart some mystical flavor to music made there comes off more like self-mythologizing. Apart from blurry assertions like, “Being there does inspire you to do it slightly differently,” or “People go to a place with a sort of magic to it,” or “There are certain places where there is a field of energy,” the film offers little explanation of why the “Muscle Shoals sound” was so fertile.

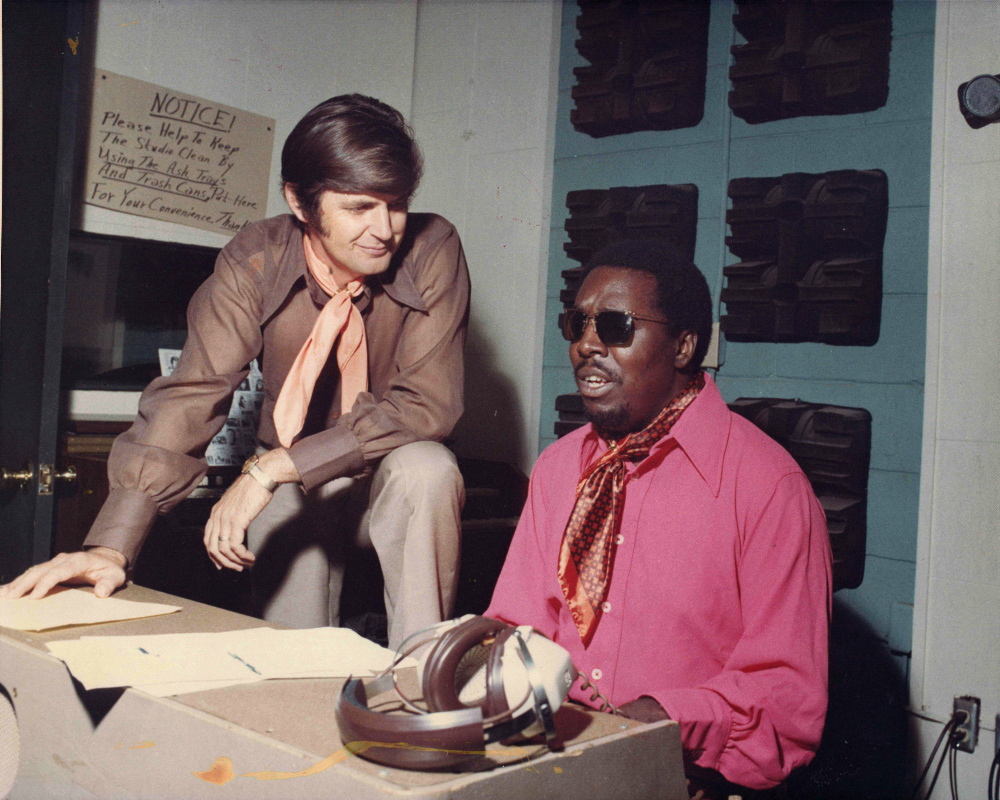

More convincing, and fascinating, is the documentary’s portrait of driven producer Hall and his chosen backup players The Swampers, possibly the least-likely soul, R&B, and rock gods imaginable, and how Hall’s modest Fame Studios became the most sought-after recording facility in the world. Hall, presented as an irascible, exacting perfectionist needed a backup band to record with local African-American singers and hired The Swampers, a group of white teenagers. Backing up black singer Arthur Alexander, The Swampers provided a layered, shockingly funky groove which soon led to Alexander’s songs being covered by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones – and brought the world knocking on Fame Studios’ doors in search of its signature sound. They were in for a shock (as was I) – as Bono puts it, “People came expecting black guys and instead found a bunch of white guys who look like they work at the supermarket.”

The racial aspect of the film is both idealized and underdeveloped, but never less than fascinating, with numerous musicians extolling how Fame operated as an oasis of harmony in the 1960s Deep South, with black and white musicians coming together in harmony in pursuit of, well, harmonies. The present day Swampers (who eventually broke off to set up the equally-legendary 3614 Jackson Avenue Studio across town) indeed look like nothing less than everybody’s soft-spoken uncles, but they, indeed provided the backbone to some of the most indelible R&B songs of all time. Aretha Franklin, who admiringly states, “I didn’t think they’d be as greasy as they were,” sings in front of them on “I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You,” and “Respect.” They were Percy Sledge’s band for “When a Man Loves A Woman.” That’s them on The Staples Singers’ “I’ll Take You There,” and Jimmy Cliff’s “Sitting in Limbo.” And when the Rolling Stones came to Muscle Shoals in order to partake of the town’s soul history, The Swampers (aka The Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section) were the session men on “Wild Horses” and “Brown Sugar.”

The list of artists who enlisted The Swampers and/or Rick Hall to bring that Muscle Shoals sound is astounding. The film, which ambles alongside the soft, Southern voices of now-old men and languorous shots of the unassuming Alabama countryside that, for reasons that remain unclear, gave rise to one of the most unsung and influential movements in American music, may not provide many answers. But it, like Muscle Shoals itself, provides a hell of a lot of great music.

Dennis Perkins is a Portland freelance writer.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.