BURLINGTON, Vt. — The number of patients at Vermont’s largest hospital who have developed infections from having catheters inserted into the central veins of their chests has dropped to about a 10th of the national rate in the two years since doctors changed how the procedure is performed.

Doctors and nurses have been trained – and retrained – in the technique developed at Burlington’s Fletcher Allen Health Care to prevent infections caused by the central venous catheters, which are inserted through patients’ shoulders, and used when physicians want to have several drugs running into the patient at once.

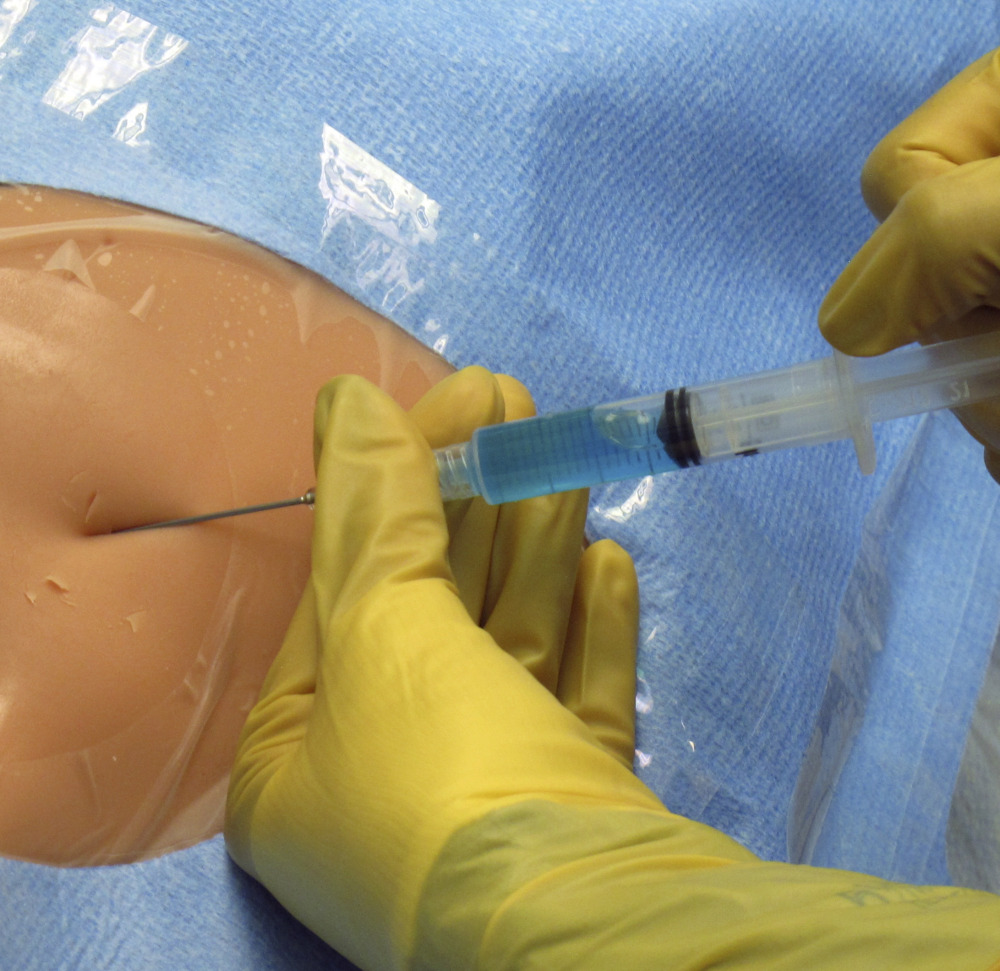

The new protocol has meant breaking old habits, practicing using simulation mannequins, paying close attention to medical records to ensure proper procedures are followed, and giving nurses the power to challenge doctors.

“This is a monumental task,” said Dr. Gilman Allen, the Fletcher Allen pulmonary specialist who is hoping to publish a paper about their results. “It basically involves everybody.”

Since the new system began at Fletcher Allen, the central line infection rate in the medical intensive care unit was 0.15 per 1,000 catheter days, about a tenth of the national median of 1.2. In the 18 months before the new system was implemented the rate was 2.72, Allen said.

Physicians began to question the long-held assumption that some central line infections were an inevitable byproduct of treating acutely ill patients about 15 years ago. Federal health insurance providers no longer pay to treat them.

Central lines are typically used on critically ill patients when drugs cannot be delivered through a standard IV, or when the goal is for the drugs to pass rapidly through the heart. They have a much higher risk of infection because the line is left in for days, providing a continuously open passageway for bacteria to get into the blood stream, Allen said.

The system at Fletcher Allen trains nurses to spot breaches in protocol and gives them the authority to stop a procedure if they notice the physician has missed a step or inadvertently broken the sterile procedure. That challenges an age-old medical pecking order that left the physician the top word in any medical procedure.

“The physician has to be receptive to that and be willing to stop what they are doing and redirect the procedure so that it’s done properly and sterilely,” Allen said.

And established physicians with years of experience are also retrained in the new techniques. The hospital said there has been little resistance.

Dr. Alfred Croteau, one of the first physicians to be trained on the new system at Fletcher Allen, now helps teach the technique in the hospital’s simulation lab, run by Fletcher Allen, the University of Vermont College of Medicine and the college of Nursing and Health Sciences.

One recent morning, the third-year surgical resident re-taught two young physicians. He started at the most basic level by showing them the central line kits developed for Fletcher Allen, and how to put on a surgical gown, particularly the gloves. He then showed them how to hold the needle while inserting it into the shoulder of a plastic torso that includes the artery and vein beneath the clavicle bone. “The old saying was ‘see one, teach one, do one,’ an old surgical mantra, and now they are really moving away from that,” Croteau said. “You can gain a lot of expertise here in the (simulation) lab with things that don’t even look like a human.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.