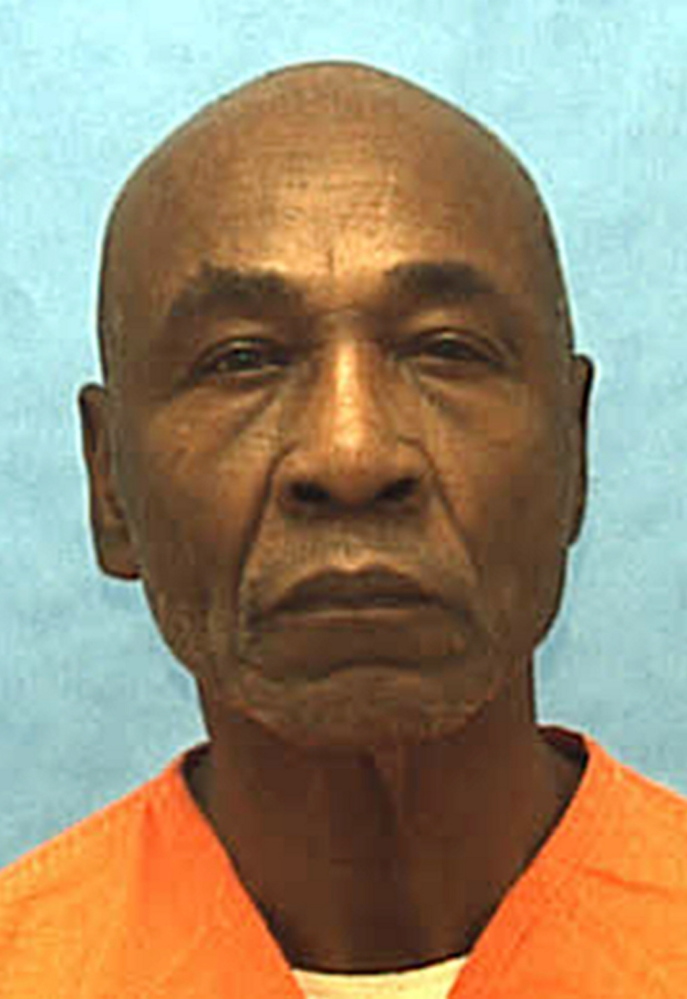

WASHINGTON — Florida officials say Freddie Lee Hall is smart enough to die for what he did.

On Monday, 36 years after the double murder that sent Hall to death row, the Supreme Court will consider whether Florida is right. The court’s answer could mean life or death for Hall and other inmates whose below-average intelligence puts them on the borderline of eligibility for execution.

“This is a significant case because a decision the wrong way could lead to longer delays in carrying out sentences,” Kent Scheidegger, of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation in Sacramento, Calif., said Friday.

The American Bar Association shares the sense of significance, but for a different reason. The lawyers’ organization warns that if Florida wins, “the execution of individuals with mental retardation” could be inevitable. With their competing legal briefs, Scheidegger and the bar association joined others in trying to sway the court in advance of Monday’s hourlong oral argument.

The Supreme Court has already ruled out executing those variously called “mentally retarded” or “intellectually disabled,” as a violation of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. The case Monday concerns the standards that states can use in defining who is disabled.

Hall is an illiterate 68-year-old high school dropout who has spent well over half his life in prison. His tested IQ has ranged as low as 60 and as high as 80. Most of his IQ test scores have hovered in the low 70s, well below the 100 average but slightly above Florida’s strict threshold of 70 for determining intellectual disability.

Besides an IQ of 70 or below, Florida requires “deficits in adaptive behavior” and an onset before the age of 18 for those who claim intellectual disability. The court’s focus Monday is on the strict IQ score requirement, with Hall’s supporters arguing that a test’s margin of error should be taken into account. A margin of error means that someone might score 75 one day and 70 the next.

“Simply put, IQ test scores are not perfect measures of a person’s intellectual ability,” Hall’s Tampa-based attorney Eric C. Pinkard and others wrote in a legal brief.

Florida has Idaho, South Carolina and seven other states on its side, arguing that the Supreme Court should give individual states “substantial leeway” in determining intellectual disability. If a state wants to set a strictly numerical IQ threshold as part of the assessment, as Florida has done, the high court shouldn’t interfere, these officials say.

“Florida did not manufacture its IQ threshold out of thin air,” Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi and Solicitor General Allen Winsor wrote in a legal brief, adding that the justices have “traditionally deferred to legislative judgments on scientific questions.”

The Florida officials’ brief further puts a spotlight on Hall’s actions on Feb. 21, 1978.

At the time, Hall was on parole. He and an accomplice kidnapped a 21-year-old pregnant woman named Karol Hurst and drove her to a remote location. Hall says it was his accomplice who then raped and killed Hurst. The accomplice blamed Hall. The two men subsequently killed Hernando County Deputy Sheriff Lonnie Coburn, under circumstances that remain cloudy.

Hall’s accomplice was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.