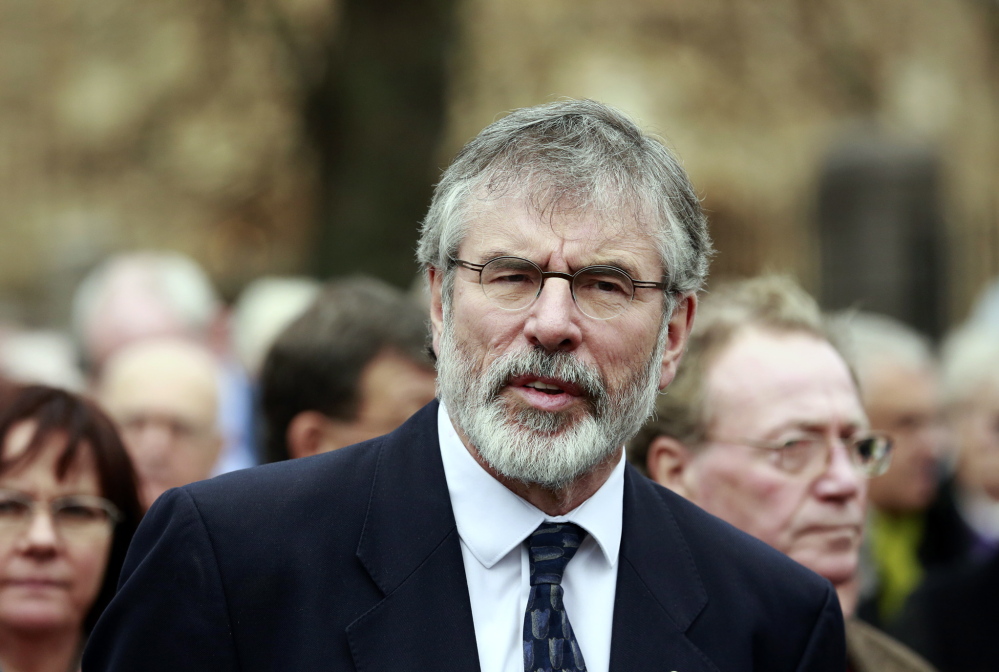

BELFAST, Northern Ireland — For decades, Helen McKendry has demanded that Sinn Fein chief Gerry Adams come clean about the Irish Republican Army’s abduction, slaying and secret burial of her mother in 1972 and his alleged role as the outlawed group’s Belfast leader who ordered the killing.

As detectives interrogated Adams for a second day over the unsolved slaying of the 37-year-old widowed mother of 10, who was falsely branded a British spy, the daughter who led a campaign for the truth says she’s praying for a murder charge.

“I’m hoping against hope that he doesn’t walk out free,” McKendry told The Associated Press. “Everybody, the dogs in the street, knew he was the top IRA man in Belfast at that time.”

McKendry, alongside her husband Seamus, launched an often-lonely protest campaign in 1995 against Adams’ denial of IRA involvement in the slaying of Jean McConville. On Thursday, the 56-year-old said she found it hard to believe he was finally in custody and facing police questions.

Under British anti-terror law, Adams, 65, must be charged or freed by Friday night, unless police seek a judicial extension to his interrogation.

Northern Ireland has met news of Adams’ arrest for the 42-year-old crime with a mixture of resignation and cynicism. Supporters and detractors alike agree on one thing, though: Adams is too important a figure in the peace process to go to jail, and he’s never going to talk honestly about his past command positions in the Provisional IRA.

The underground army killed nearly 1,800 people – including scores of Catholic civilians and IRA members branded spies and informers – before calling a 1997 cease-fire so Sinn Fein could pursue peace with Britain and Northern Ireland’s Protestant majority.

Two decades ago, Adams initially insisted in brief face-to-face meetings with the McKendrys that the IRA was not involved. Finally in 1999, the IRA admitted responsibility for the slayings of nine long-vanished civilians and IRA members, including McConville, and offered to pinpoint her unmarked grave on a beach 60 miles south of Belfast in the Republic of Ireland.

That effort failed despite extensive digging. Then in 2003, a dog walker stumbled across her skeletal remains, with its bullet-shattered skull, protruding from a bluff above a different beach.

It was the bitterest of victories for the orphaned McConville children, whose lives were indelibly scarred by her disappearance. At the time, they ranged in age from 6 to 17; McKendry was 15. Since their father had died of cancer in 1971, authorities placed them in different foster homes and the children grew up strangers to each other.

Some siblings became IRA supporters themselves and believed the IRA’s depiction of their mother as a British Army scout armed with a walkie-talkie who passed along sightings of IRA gunmen in her neighborhood.

McKendry says her mother’s background as an outsider – she was raised a Protestant in east Belfast but moved to Catholic west Belfast after her marriage to the children’s father, a Catholic – fueled irrational IRA suspicions.

Northern Ireland’s independent police complaints watchdog investigated the IRA’s spying claims and cleared McConville’s name in a 2006 report.

Some of the siblings were relieved they finally had a mother to bury.

But McKendry kept pressing to get the IRA members allegedly behind her mother’s disappearance convicted of murder, particularly Adams, who according to former IRA members commanded the unit responsible for making suspected Belfast informers and spies vanish in the early 1970s.

If criminal prosecutions fail, she plans to sue Adams for civil damages.

“I couldn’t get to the end of my life not knowing what happened to my mother. I had to take a stand, to tell the world what happened,” she said. “But Adams is never going to admit anything. He’s never even going to admit he was in the IRA.”

The police investigation of the McConville killing has accelerated since detectives last year received a potential treasure trove of taped interviews with IRA veterans recorded in a Boston College-commissioned oral history project.

While the IRA members spoke candidly on condition the audiotapes remained under lock and key until their deaths, the Northern Ireland police sued for access to all of them after one of the interviewees, Brendan Hughes, died and his accusations against Adams were published and broadcast in 2010.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.