The Portland Symphony Orchestra led off its April 27 concert with a confection by Antonin Dvorak entitled “Mein Heim (My Home) (Op. 62, B.125a). While pleasant to hear, its importance lies in the trend it exemplifies: the movement from “art music” toward nationalism in the latter part of the 19th century.

Examples come immediately to mind: Sibelius’ “Finlandia,” Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture,” Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies, all of Wagner, the Chopin “Revolutionary Etude,” Smetana’s “Ma Vlast (My Country). The impressionist movement of Ravel and Debussy can be seen as a reaction to what they regarded as Germanic music.

Although serious composers often used folk tunes of their own or other countries, they did not often play on the strings of patriotic emotion, since their works were written for aristocrats and connoisseurs, who regarded themselves as citizens of the world, or at least of Europe.

The trend’s logical culmination was the rise of the national anthem, as opposed to earlier music written for a specific monarch, such as Haydn’s Kaiser Hymn, now the German national anthem and musically by far the best of the lot. (The tune is used for the hymn “Glorious things of thee are spoken.”) The Austrian national anthem is supposedly a melody by Mozart, but probably is not.

Others on the short list of classical composers of anthems include Rabindranath Tagore, India and Bangladesh; Rikard Nordraak, Norway (not Greig!); Zubir Saaid, Singapore; and Charles Gounod, the Vatican City State.

What is really frightening is that not a single country in the world is without a national anthem except the island of Cypress, which uses those of Greece and Turkey.

Why frightening? Because many of them – no one in his right mind would try to listen to them all – appeal to the lowest common denominator of jingoism, the kind of patriotism to which Samuel Johnson was referring when he called it “the last refuge of a scoundrel.”

The usual form is the commemoration of a forgotten mutual slaughter in bad verse and worse music. Take the “Star Spangled Banner,” for example: “The text of the song is largely the reflection of a single war-time event which cannot fully represent the spirit of a nation committed to peace and goodwill,” said the Music Supervisors’ Conference of America in 1931, when “vigorously opposing” its adoption as the national anthem.

Here’s one you’ll never hear:

Eagerly, musician.

Sweep your string,

So we may sing.

Elated, optative,

Our several voices

Interblending,

Playfully contending,

Not interfering

But co-inhering,

For all within

The cincture

of the sound,

Is holy ground

Where all are brothers,

None faceless Others,

Let mortals beware

Of words, for

With words we lie,

Can say peace

When we mean war,

Foul thought speak-fair

And promise falsely,

But song is true…

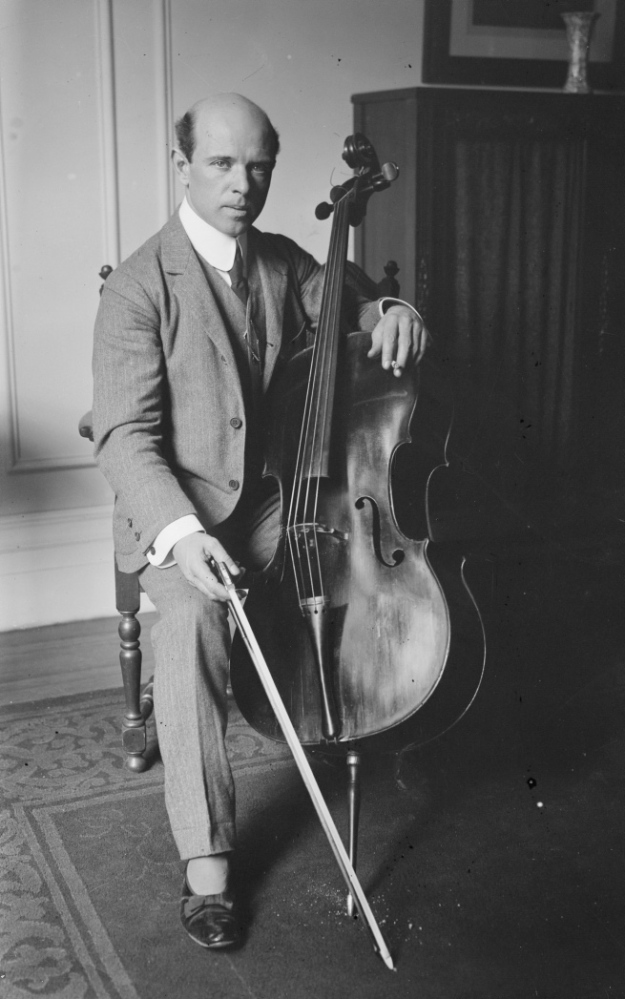

Lyrics by W.H. Auden and music by Pablo Casals. It’s a hymn to the United Nations to be regarded as a world anthem. Auden’s line in “1939,” written in better days, would have been more appropriate: “We must love one another or die.” That could be set to the Ugandan national anthem of eight bars.

Christopher Hyde is a writer and musician who lives in Pownal. He can be reached at:

classbeat@netscape.net

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.