It had taken a while, but Army Staff Sgt. Sam Shockley had meticulously compiled a list of all of his war wounds, including his diminished memory, only to leave it sitting in his bedroom as he went rushing off to his appointment.

There was no time to go back and grab it. He would have to do the best he could.

“We’ll start from the head and work our way to the bottom,” Shockley told Reggie Washburn, a Department of Veterans Affairs benefits counselor who in the next few hours would help Shockley figure out the true cost of his war. “As long as I go from head to toe I’m pretty sure I’ll remember all my points.”

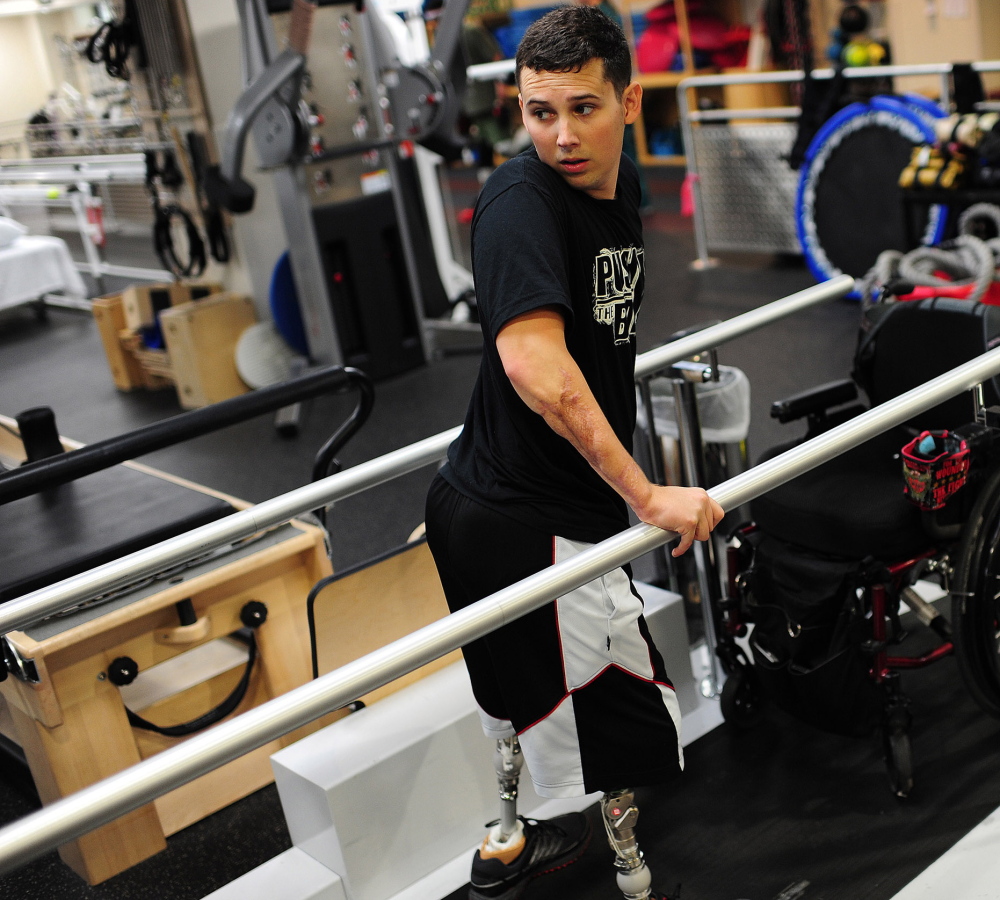

One year earlier, Shockley, then 25, was leading his squad through a field in southern Afghanistan when he stepped on a buried bomb that shot him into the air and sheared off his legs. Now, after 40 surgeries, he had come to the small VA office in Bethesda, Maryland, at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, to start the process that would determine the monthly disability payments that he’ll receive for the rest of his life.

War can be a series of cold calculations: The distance a bullet travels, the blast radius of a bomb, the minutes it takes to reach a soldier bleeding out on the battlefield. For wounded troops leaving the military, there is one more: The price paid for a broken body, a missing limb, a lost eye, a damaged brain.

LONGEST STRETCH OF FIGHTING

The longest stretch of fighting in U.S. history is producing disability claims at rates that surpass those of any of the country’s previous wars. Nearly half of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans are filing for these benefits – a flood of claims that has overwhelmed the VA and generated a backlog of 300,000 cases stuck in processing for more than 125 days. Some for more than a year.

“We’re not where we need to be,” President Barack Obama. “But we’re making progress.”

If the backlog is going to be fixed, the solution will come one soldier at a time in small offices such as this one at Walter Reed.

“So we’ll start with the head portion,” Shockley said. “I know I had a ruptured eardrum.”

“Is that the right ear?” asked Washburn. He sat behind a metal desk with a window overlooking Tranquility Hall, the dorm where Shockley lives with his fiancee while he learns how to walk on prosthetic legs and rehabilitates his body.

“Left ear,” Shockley said.

Washburn logged the information. Shockley’s medical records rested on the floor.

“I guess we’ll move on,” Shockley said. “Concussion, obviously from the blast.”

He continued down his body: One of Shockley’s lungs collapsed. His lower back is chronically sore. There’s scarring and nerve damage on his forearm. There’s a metal plate in his wrist. He’s missing parts of his middle and index fingers. There’s a missing right testicle. One leg is gone above the knee and the other below the hip.

Shockley moved on to the less visible wounds. He sometimes suffers from migraines, though they have waned.

“Is that something you want me to list?” Washburn asked.

“Might as well,” Shockley said.

He has trouble sleeping. The heavy narcotics he was given following his surgeries wreaked havoc on his digestive system.

“How about memory loss?” asked Washburn.

“Quite a bit of short-term memory loss,” Shockley said.

Shockley paused and ran through his wounds one more time to make sure he wasn’t forgetting anything: “Arm, finger, lung. We got the lower back,” he said. He glanced down at the place where his legs used to be. “I really can’t say anything about knees or ankles,” he said.

Washburn was seeing where this conversation was headed. Shockley was his third interview of the day and one of hundreds that he’s done since coming to Walter Reed 18 months ago.

He has seen some troops grow angry as they think about how their wounds have changed their lives. “You don’t understand the frustration,” railed one Marine as he talked about being unable to open his car door wide enough in a crowded parking lot to load his wheelchair. Some troops choose to laugh. “Taco Bell tonight!” joked one when Washburn told him that his missing foot and ankle would earn him an extra $101.50 a month in disability.

On the day he stepped on the hidden pressure plate, triggering the explosion, Shockley was sweeping the path in front of his squad with a metal detector.

“I would’ve rather stepped on it than anyone else,” Shockley said, repeating something that he’d said to himself so many times over the past year that it had almost become a mantra.

Shockley had been sitting across from Washburn for almost an hour, and his lower back was beginning to throb. The incision from his last surgery was starting to sting. He grabbed a low-dose Oxycontin pill placed it on his tongue. He didn’t have any water, so he snapped his head back with a practiced jerk, and the pain pill slid down his throat.

In the year since the explosion, Shockley had come to know people throughout Walter Reed, including the military doctors upstairs who sometimes wondered about the lives they were now able to save. In Afghanistan, the doctors had debated whether they should even be saving these troops. What kind of lives could they lead?

Today, these doctors ask other questions: How will these veterans cope when pressure sores force them back into their wheelchairs? What will happen to their battered bodies as they age? Will they grow depressed?

Shockley offered one answer. “I always think it could be worse,” he said.

His list of wounds now done, Shockley rattled off a list of blessings and accomplishments. “I would say I came out of this with my head on my shoulders,” he said.

He had served three tours of Iraq and Afghanistan and had been promoted faster than many of his peers. Most important, he had made it home alive. “I’m glad I didn’t die in that hell,” he said.

Washburn finished up the last of the paperwork as Shockley talked about some of the things he hoped to do in the years ahead: Get married. Go back to school. Maybe he’d find a career in the private sector and retire at 50 to the Caribbean.

ITEMIZED DISABILITY

Washburn nodded and then began telling Shockley about the benefits he would be receiving. He would almost certainly be judged 100 percent disabled, entitling him to a minimum monthly payment of $2,858. He’d also receive special monthly compensation. The loss of a single foot, hand or eye is worth $101.50 a month. Two missing legs can generate an additional $1,000-$1,300 a month. Missing arms are worth an extra $1,600-$1,800. The highest rate of disability compensation – typically reserved for veterans requiring near-constant assistance – is $8,179 a month.

“You know there was another thing I kind of forgot to mention,” Shockley said,. “I know on my . . . We talked about the . . .” He paused and took a breath. “It was complete damage to that testicle region. One testicle made it through, but I am completely infertile.”

Washburn hit print on his computer and handed Shockley the final list. Shockley would be examined by VA doctors who would assess the severity of the listed wounds. A VA claims processor in Seattle would review the reports, along with Shockley’s military medical files, and propose a disability rating.

The entire process, if everything went smoothly, would take six months. Whenever it was complete, Shockley would return to Washburn’s office for one last meeting.

There, Shockley would learn just how much his war was worth, and the VA backlog would consist of one fewer soldier.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.