Painting in Maine has long been marked by excellent brushwork, skill and craftsmanship – the very stuff of painterly abstraction. But Maine has hardly ever been associated with abstraction.

So what is the relationship between painting in Maine and abstraction?

This has been an increasingly common studio topic that spilled its banks into public conversation when photorealist-turned-abstractionist Mark Wethli recently organized a well-received show featuring a cadre of Maine abstract artists at New York’s Curator Gallery. (“Second Nature: Abstract Art from Maine” featured work by John Bisbee, Meghan Brady, Clint Fulkerson, Cassie Jones, Joe Kievitt, Andrea Sulzer as well as Wethli.)

Since the 2011 centennial of abstract painting, I had been wondering when (or if) Maine would turn the corner on abstraction. Now, I think it has.

I have long loved the Corey Daniels Gallery’s space – an intoxicating combination of wizened beam ceilings floating above concrete floors and sophisticated minimalist architecture. But it had never before seemed fully dedicated to art over antiques. Daniels’ “Install 4” features the work of three established Maine abstract artists – Jeff Kellar, Frederick Lynch and Duane Paluska – and it might be the most elegant exhibition I have ever seen in Maine.

With about 100 works by the headline trio, it’s a huge show. But it breathes. And where you expect reductive abstraction’s insistent distance between the art and the viewer, the craftsmanship of these artists’ work invites intimacy, which it lusciously rewards.

From a distance, Kellar’s spatial but spare resin, clay and pigment paintings on floated aluminum panels follow their architecture-inspired minimalist drawings to fold and unfurl in space. But their details draw you in close, at which point the gorgeously burnished surfaces act more like inlaid wood or clay.

A few minutes around Kellar’s work make it readily apparent why he won a $25,000 Gottlieb Grant this spring: Kellar blends braininess and craftsmanship with exquisite geometrical grace.

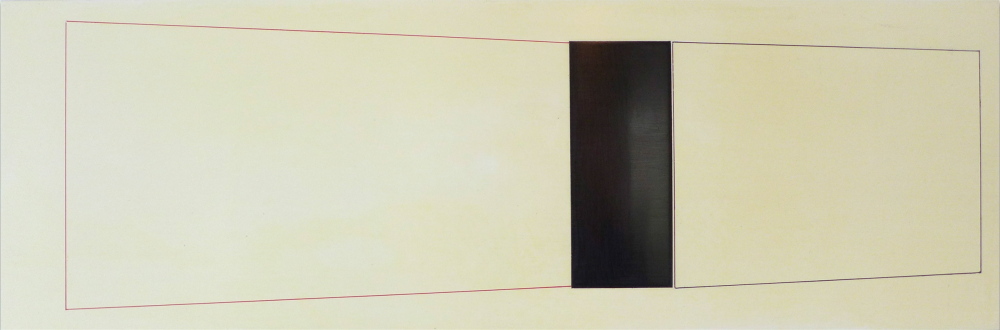

“Wall Drawing a,” for example, is a narrow creamy off-white horizontal band of a panel. It’s one of Kellar’s smaller works, but in many ways the smaller pieces are more powerful since they pull the viewer in closer and so more effectively play the physical intimacy of the object off the idealized geometry of the images. “Wall Drawing” turns on a centered black rectangle from which simple line trapezoids emanate on either side so that they appear as a rendering of a long hallway with an “L” notched into it.

Kellar’s clear perspective system indicates a vanishing point far off to the right of the panel’s edge; so instead of stabilizing your point of view, it pushes your eye out of the image – thus incorporating the gallery wall into the range of the work. This is the kind of thing minimalist sculpture tries to do, but Kellar’s work is particularly successful because it navigates between image and object as well as between painting and wall.

This is a particularly appealing approach in such a handsome gallery space designed with an eye to textures and geometry akin to Kellar’s visual vocabulary.

The gallery is also an ideal setting for Paluska’s work. While his art has looked great in old Maine buildings bereft of straight lines, such as the Center for Maine Contemporary Art’s listing home in Rockport or Paluska’s ICON Gallery in Brunswick, here it’s easier to appreciate his sense of detail – particularly in his floor sculptures. In this setting, it’s more apparent that Paluska’s works are based in organic sensibilities rather than secret geometries.

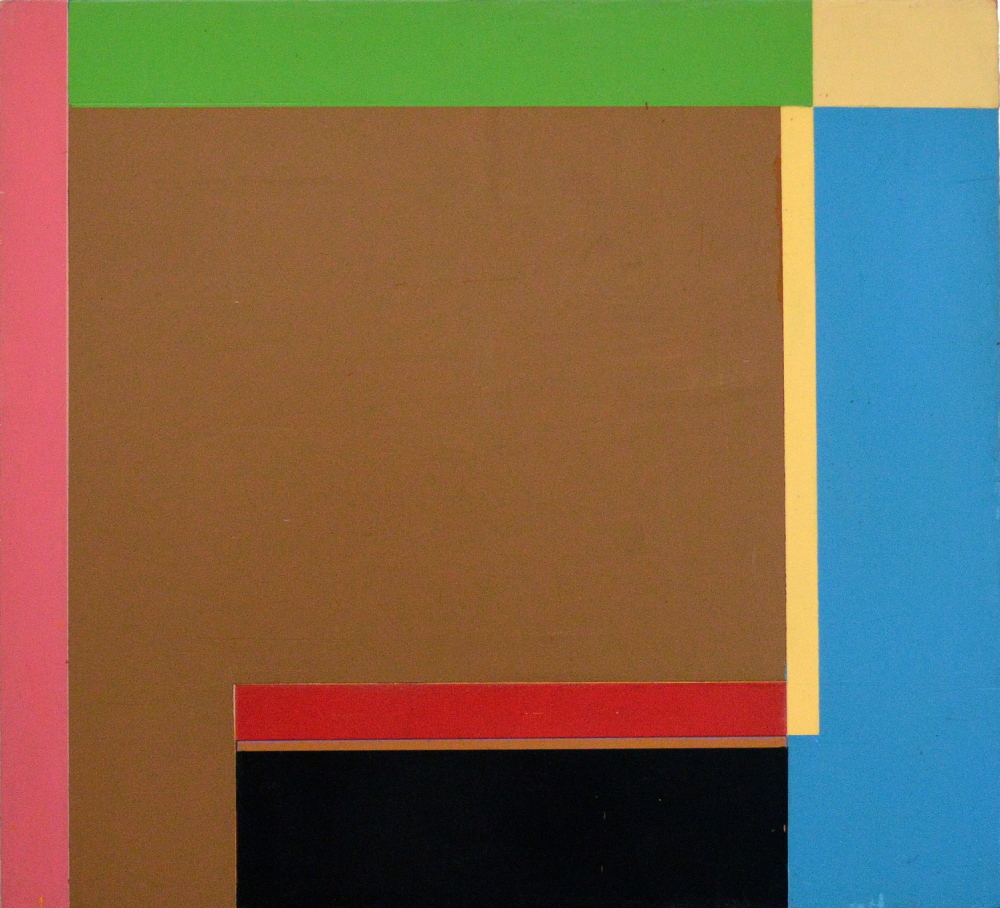

Paluska’s sculptures act like Shaker furniture that decided to do some late night ballet and then froze the moment someone turned on the light. The wall pieces in this show date back to when Paluska’s work was easily seen as hard-edge geometrical painting (as opposed to sail canvas collage).

Paluska’s “Flag 5,” for example, follows a downward spiral of rectangular forms of color towards the center of the work – pink, green, cream, blue and black – before folding back onto a red bar that leaks through a cream stripe leading to the milk chocolate center field. The work is organically painted with tape-lifted but soft edges that are played up when the panels are seen from an angle.

Lynch’s paintings assert themselves most powerfully in the gallery, but instead of reaching into the space like Kellar’s, they contain themselves. His “Division” paintings are large abstract works that seethe with broad fields of jumpy hatch marks precisely painted so they never lose their geometrical zing (or their references to scientific aesthetics). Instead of shooting out with the implied continuation of fabric patterns, Lynch punctuates the four corners of “Division Painting 1154” with gray forms that contain the motion of his seas of scintillating strokes much like photo corners in a scrapbook. These corners also have the effect of pressing us to closely examine his painterly systems with an eye to scientific observation.

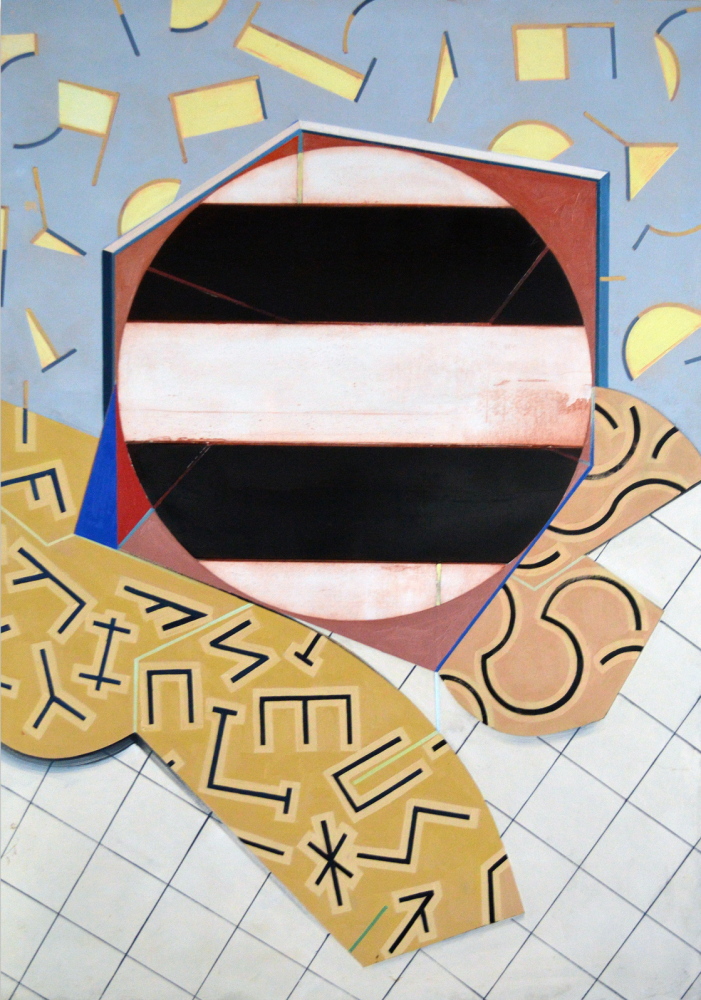

Lynch’s “Counterform” paintings are specifically about observation and the languages of painting. His “Counterform Painting #83,” for example, places a circle inside of an open cube on a patterned floor in front of a wall. It is the form and recipe of a still-life – traditional paintings generally of food that originally reflected bounty, good fortune and (therefore) wealth. Lynch’s his stellar execution makes these works clearly about the abundance of painting rather than a thanksgiving of goods: The sphere is flattened by stripes, the tiled floor flattens into pattern, the cube itself is linear and so on.

Corey Daniels is a fitting setting for Lynch’s cornucopias of art. Despite the spare aesthetics, the gallery is filled with high-design chairs and tables. Laid out by someone with an exquisite eye, it’s an abundantly comfortable place for people.

Is it ironic to talk about the arrival of abstraction in Maine despite the fact that Daniels and Paluska both opened their galleries over 20 years ago?

I don’t think so: Something has changed.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.